Amid President's Resignation, University Of Missouri Students, Alumni Say Protests A Product Of Longstanding Racial Issues On Campus

It felt off for Kennedy Robinson, who is African-American, when she joined the predominantly white Sigma Kappa sorority her freshman year at the University of Missouri. She never felt like she belonged. After being initiated as a sister, Robinson said she left Sigma Kappa after just one month.

"I felt like I was an outsider, so I dropped it after that," she said in a phone interview Monday. Nobody was outright mean to her, but she said it was uncomfortable. "They didn't know how to talk to me," said Robinson, now a 21-year-old senior.

Amid a spate of racially charged incidents and days of student-led protests, University of Missouri President Tim Wolfe announced Monday he would resign. Wolfe's resignation followed a threat by the school's football team to abstain from playing, which would have canceled Saturday's scheduled matchup against Brigham Young University and put the already nationally publicized situation under further scrutiny. Robinson's experiences have mirrored accounts from some current and past students, showing the dramatic events of the last few days at Missouri were the outcome of long-simmering racial issues at the university.

Final Strike

Robinson said she did not regret her choice of university, but did have her reservations about the culture on campus. "I do notice that Mizzou is segregated," she said. "I don’t really see a lot of the black community and the white community mixing."

Many say there are longstanding race issues at Missouri. The protest group pushing for Wolfe's resignation took on the moniker "Concerned Student 1950," referencing the year the university first admitted a black student. In 2010, two white, male students placed cotton balls in front of the black culture center on campus, an incident viewed as an implicit reference to plantation slavery. In that case, both students were charged with littering.

During the protests last year in Ferguson, Missouri, after the killing of unarmed black youth Michael Brown by a white police officer about 116 miles east of Columbia, an anonymous threat surfaced on the social media app Yik Yak that said, "Let's burn down the black culture center & give them a taste of their own medicine," according to the Los Angeles Times.

Then, in September, the head of the Missouri Student Association, Payton Head, who is black, wrote in a Facebook post that a man riding past in a truck yelled a racial epithet at him.

"For those of you who wonder why I’m always talking about the importance of inclusion and respect, it’s because I’ve experienced moments like this multiple times at THIS university, making me not feel included here," he wrote.

Later, allegations emerged that a drunken white student yelled racial slurs at a black students’ organization ahead of the university's homecoming parade. Finally, a swastika made of human feces was discovered Oct. 24 in a dorm bathroom.

Protests, notably one led by a five-day-long hunger strike launched Nov. 2 by 25-year-old graduate student Jonathan Butler, would soon emerge and were eventually joined by the football team and backed by head coach Gary Pinkel, who is white.

The Mizzou Family stands as one. We are united. We are behind our players. #ConcernedStudent1950 GP pic.twitter.com/fMHbPPTTKl

— Coach Gary Pinkel (@GaryPinkel) November 8, 2015African-Americans compose much of the Missouri football team. In contrast, the university is some 75 percent white and about 7 percent black. The attention placed on the team's protest helped spur real change on campus.

"It's about more than football. More than scholarships. I'm just happy our athletic department was behind us," Trevon Walters, a running back for Mizzou, told the Columbia Missourian newspaper after Wolfe's resignation Monday. Sports pundits and fans had wondered if the team, amid suggestions that some players disagreed with the strike, really would carry out the threat to force the cancellation of a game worth significant dollars to the university.

"There’s always a concern on how far you have to go. A lot of things got done and a lot of things got accomplished," defensive end Walter Brady told the local paper following Wolfe's announcement.

The athletic department at Mizzou was not immediately available for comment but did provide a statement following Wolfe's resignation and planned a news conference later in the day.

"The primary concern of our student-athletes, coaches and staff has been centered on the health of Jonathan Butler and working with campus leaders to find a resolution that would save a life," said Pinkel and university Athletics Director Mack Rhoades in a joint statement. "We are hopeful we can begin a process of healing and understanding on our campus."

Trevon Walters: "It's about more than football. More than scholarships. I'm just happy our athletic department was behind us."

— Aaron Reiss (@aaronjreiss) November 9, 2015#Mizzou's Walter Brady: “There’s always a concern on how far you have to go. A lot of things got done and a lot of things got accomplished."

— Aaron Reiss (@aaronjreiss) November 9, 2015The move from the football players and student body was met with some criticism but backed by many who felt the time for change had come. "I applaud the students and football players taking a stand," said Michelle Freeman, a 1998 graduate from the University of Missouri's Kansas City campus. Freeman, who is African-American, added, "There [have] been longstanding problems with students of color and the University of Missouri system."

'Night And Day Different'

Black graduates from the University of Missouri recounted stories of discomfort at their alma mater. Jazmin Burrell, who graduated from the school last May, said a lack of diversity could be felt the classroom.

"If you’re not studying black studies, you’re probably not going to get a black teacher," the 23-year-old said. Burrell was involved in diversity initiatives on campus and stressed that Monday's developments could be directly traced back to a group called MU4MikeBrown that was led by two African-American women.

Wolfe's resignation was a major event that "needed to happen," Burrell said. "The racial climate [at Mizzou] has always been tense."

The group behind the most recent protests released a list of demands, and many have said that Monday is just the beginning. It remains to be seen what the next move is for the University of Missouri. Butler noted that the African-American population at Mizzou came together to make this change happen.

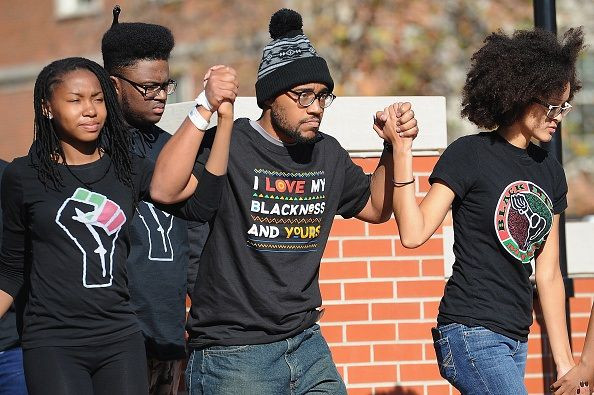

"It was the black community," he said during comments aired by CNN, noting that the day was not about his hunger strike but rather that a number of people chose to "stand united."

And here are the demands re: #ConcernedStudent1950. pic.twitter.com/k7GXVL1DiA

— deray mckesson (@deray) November 8, 2015The protesters have said they are standing against racism that pervades everyday life for African-Americans. Cynthia Frisby, a black journalism professor at the school, wrote in the Huffington Post, for instance, that she has been "called the n-word too many times to count," during her 18 years at the Columbia campus.

African-American Mizzou alum Julius Givens, 25, spoke with a staccato, but fluid, fervor about his time at the school. Givens, who graduated in 2013 and founded an art initiative for inner-city students, said he felt real tension on campus. "What happened is the school came together and said enough is enough," he said.

From being followed around by staff at the school bookstore to having to reckon with the cotton ball incident, Givens said the problem was campuswide. "The experience at Mizzou for a black student versus a white student … is night and day different," he said.

Givens noted he was never the subject of such obvious racism as being chased down and called racial epithets, but what many dub "the best four years of your life" was nonetheless shaped by his experiences on the Columbia campus.

"Everyone their entire life, you can’t wait to get to college," he said. "Well when you got to a school like Missouri [as a minority] … it's not necessarily what they all say it's meant to be."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.