Angola's $3.5B, Chinese-Built Ghost Town

The price of a one-way ticket to Luanda: $1,300. The cost of a luxury apartment in suburban Angola: $125,000. Getting friends and family to move into said housing compound inside of a Chinese-built ghost town: priceless.

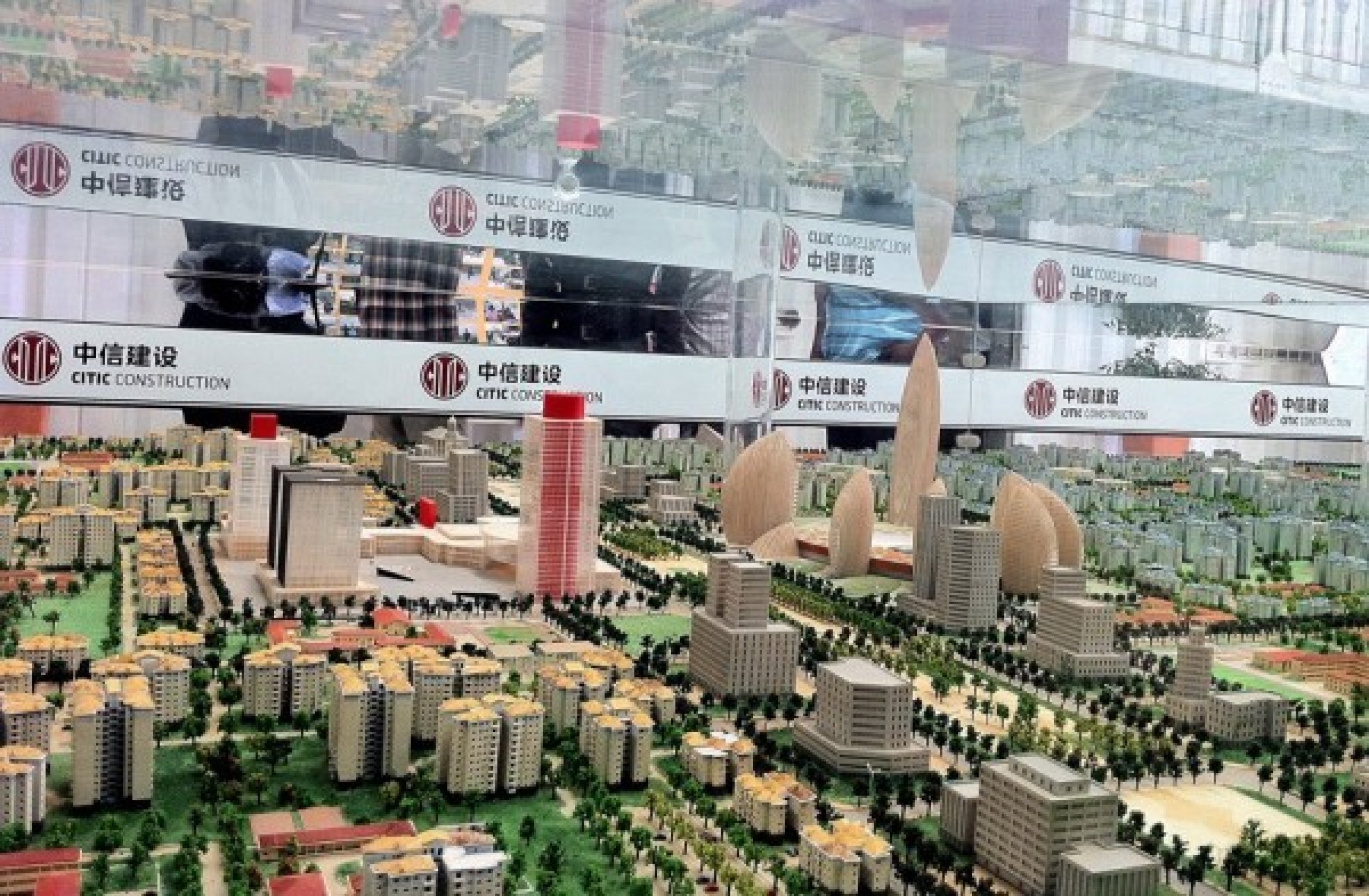

A mere 20 miles south of the capital city of Luanda, rising out of the countryside, is a mass of colorful housing blocks meant to signify modern living and modern communities in a modern Angola. Called Nova Cidade do Kilamba, the new city of Kilamba, the area is a symbol of the southwest African country's new economic wealth, founded largely on oil.

There's just one problem. No one is moving there.

Most of the area is largely deserted, according to Western media, and large numbers of buildings and shops remain shuttered and empty. The overriding majority of people that frequent the area remain Chinese and African construction workers and maintenance crew, who do not actually live on site.

China International Trust and Investment Corp., or Citic, a major state-owned investment company, is the chief financial backer behind the new town. Citic has spent $3.5 billion on the location (China is getting paid back in oil).

A promotion video for Kilamba from real estate agency Delta Imobilaria says the 20-square-mile town has more than 20,000 apartments, 41 schools and 17 health clinics. There are more than a hundred retail spaces and 750 medium-size apartment blocks being built, and soon there will be fast highway access to downtown; each housing block has a recreational center. The entire area could eventually have enough room to house some 500,000 people.

The Angolan government has spotlighted the satellite town as an example of a clean, safe and convenient living alternative to the crowded slum-ridden districts of Luanda. It is undoubtedly the country's largest housing and construction development area, perhaps one of largest on the entire continent.

But few can afford to live there.

Most of the country still survives on less than $2 per day. To pay for a low-end apartment in Kilamba, the average Angolan would need to work more than 160 years. It's no surprise, then, that less than 10 percent of the first 2,800 apartments to go on the market have been filled.

Paulo Cascao, a general manager at Delta Imobiliaria, defended the location to the BBC in early July, blaming difficulties in obtaining mortgages from Angolan banks, not the price of the location itself.

The prices are correct for the quality of the apartments and for all the conditions that the city can offer, Cascao said. However, he also qualified that the government recently declared parts of Kilamba would become redefined as more affordable social housing.

Critics of the Angolan government say the move is simply a way to gain political support for the government. The country's president, Jose Eduardo dos Santos, has ruled since 1979. Angola was mired in a devastating civil war between 1975 until 2002, with opposing factions supported by the Soviet Union and the U.S. during the Cold War. Santos, who ruled the dominant People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola led his faction to a grueling and exhausting military victory. The defeated National Union for the Total Independence of Angola and National Liberation Front of Angola are now opposition parties in parliament, though the political system is largely considered corrupt and unaccountable.

In the immediate aftermath of the civil war, more than 4 million were displaced, with half a million dead.

Since the beginning of the 21st century, Angola has made incredible economic gains, almost entirely due to rising oil sales. China, in particular, has been a major customer, with Angola now China's second-largest supplier of oil after Saudi Arabia. Yet few other industries have seen significant improvement, and, after decades of warfare and neglect, the country's agricultural production has also regressed. As the displaced resettled, many had problems finding adequate housing and jobs.

President dos Santos' 2008 pledge to build a million homes in four years seemed at the time to be a major effort to address those social and economic problems. However, if the Kalimba project is any indication, the solution has so far been wildly inappropriate.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.