China’s New Draft Cybersecurity Law Increases Controls On Internet, Allows Officials To Switch Off Web Traffic During Public Protests

SHANGHAI -- A new draft law on Internet security enshrines powers for the Chinese government to switch off the web if “sudden mass incidents” -- such as public protests -- break out. It also threatens stiff fines and possible closure for Internet companies that fail to register users’ real names and other details, or fail to delete unhealthy content and report it to the authorities.

The law also emphasizes that all Internet companies and network providers operating in the Chinese market must store their data within China, unless they apply for and obtain special exemption from the authorities. And it requires companies providing key Internet infrastructure to carry out background checks on any of their staff responsible for web security -- and requires such companies to undergo an annual inspection to check for potential security risks.

The draft law, announced by China’s legislature, the National People’s Congress, for consultation over the next month, is China’s first specifically relating to the Internet. It follows a government campaign to tighten control on the web, which China’s conservative army newspaper recently described as a cesspool of hostile Western ideas, which were leading young people astray and seeking to bring down the Communist Party.

To some extent, its content simply formalizes rules that already exist in practice. Its stipulation that the central government, or governments at the provincial level, can, “if necessary… carry out measures including restricting internet communications in specific regions to protect national security and social order, and to prevent major sudden incidents affecting the safety of society,” for example, is a reminder of events in 2009, when the Chinese government turned off the web in the northwestern region of Xinjiang for more than six months following race riots in the capital city Urumqi, which left at least 197 people dead.

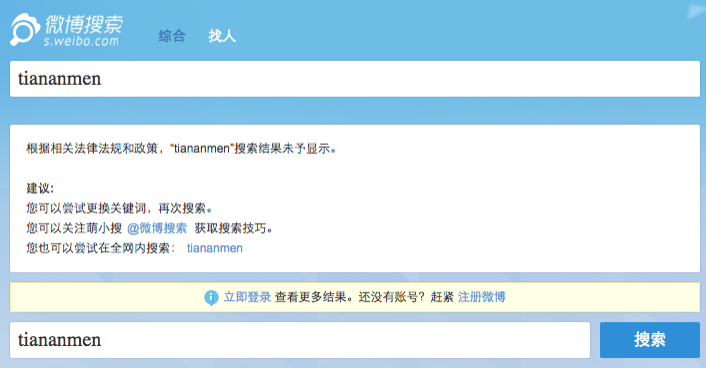

And the government already requires Chinese social media sites to register their users with real names in theory -- in order to keep tabs on what they post. However major Internet companies such as Sina.com, which operates the country’s biggest micro-blogging site Sina Weibo, have admitted in the past that they have not fully implemented this rule.

And Maya Wang, a Hong Kong-based researcher at Human Rights Watch, told International Business Times that the new law -- which threatens fines of up to half a million yuan (about $80,000 dollars) or even closure of websites, for refusing to register -- “may speed up the pace of companies” complying with the policy.

Wang also said the new law may also make it harder for Internet companies to delay deleting sensitive posts: “Right now it's not uncommon for Weibo users to post messages with one Weibo service rather than the other because they know it doesn’t delete posts as much or as fast. But legally requiring them to do so may reduce the wiggle room that’s previously existed.”

And she said that while the possible exception to the requirement to store all data in China “seems to be a step-down” from an earlier proposal that all data must be stored in China -- something that had alarmed foreign Internet companies doing business in China -- it still showed that “the government wants data to be localized to give it greater control over it.”

It also emphasizes the responsibility of local governments in enforcing these rules, saying they should carry out regular exercises aimed at preparing for dealing with a major Internet security lapse.

Overall, observers say the new rules are aimed at emphasizing the government’s determination to control “cyberspace:” it also made “cyber security” a key plank of a new security law passed last week, while the central leadership under President Xi Jinping has set up a “leading group” to focus on threats from the Internet. These are seen as including threats from both foreign hackers and Chinese citizens, who have become increasingly outspoken online in recent years.

The new law therefore sends a clear message that the government “intends to further tighten the screws over online expression,” Wang said. It follows the introduction of a new national security law, anti-terrorism law and nonprofits law -- all of which have been seen as potentially limiting civil society action. Wang said it is the final step in the government’s attempt to “construct an interlocking set of laws that will maintain internal stability and put Chinese citizens in a ‘cage of law.'"

At the same time analysts pointed to the vagueness in this law -- like several of the others -- as allowing the authorities plenty of room for interpretation in dealing with behavior they didn’t like: it says, for example, that citizens should not only “obey laws and constitution” in their online behavior, but should also “respect public order and social morality… and must not … damage social order, or harm public advantage,” without appearing to define these. The potential for interpretation was highlighted by the recent detention of one of China’s best known civil rights lawyers, Pu Zhiqiang, who was charged with “inciting ethnic hatred” (a phrase also used in the draft law) after questioning whether government policy in Xinjiang had increased social tensions in the region, where some Muslims have engaged in armed resistance against the authorities.

The draft law also appears to increase efforts to encourage the public to denounce others who they suspect of violating its clauses: the government has already sought to mobilize 10 million volunteers to help create what it calls a clean and positive cyberspace -- and it stipulates that “everyone has right to inform on any behavior that harms web security” and calls on schools and colleges, as well as the mass media, to “promote education on cybersecurity.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.