Did A Hunger Strike Free Samer Issawi, A Palestinian Terrorist To Israelis And Heir To Gandhi To Arabs?

JERUSALEM -- Everyone in the small East Jerusalem suburb of Al-Issawiya knows where Samer Issawi’s house is. Ask any driver of the Arab-run buses that weave down the narrow streets of Mount Scopus, past Hadassah Hospital, to the community of just 35 families that looks out over the separation wall toward the West Bank. The drivers drop people right outside the front door of his family home.

On this particular morning, trays laden with elaborate coffee carafes and Arabic sweets await guests in a large sunroom at the back of the family's nicely furnished house. Visitors begin to fill the sunroom by midmorning, then gradually overflow into the lounge. By lunchtime they have spread onto the rooftop terrace.

Issawi isn’t a celebrity in the conventional sense – he’s not a wealthy benefactor or a famous actor or musician. He’s a man who not long ago ended a nine-month hunger strike. To the Israelis, he’s a terrorist and an inveterate criminal. To the Palestinians, he’s a political dissident, the spiritual scion of civil disobedience activists like India’s Mahatma Gandhi and Bobby Sands of the Provisional Irish Republican Army, who died as a result of a hunger strike in 1981.

In Issawi’s case, the lowly status of Palestinians in Israel was the larger issue he hoped to call attention to via his actions, but his view that he had been imprisoned without a fair trial was his specific complaint. Issawi is free now, so the narrative among Palestinians is that the hunger strike worked. And though the Israeli police warned Issawi’s family not to celebrate his release from prison, their daily festivities have gone on without interruption.

“By the end of the day, there will be people dancing in the lounge and on the roof,” Issawi’s sister Shireen says. “Some people have even jumped the separation wall from the West Bank to come to the house because they can’t get permission from Israelis to come.”

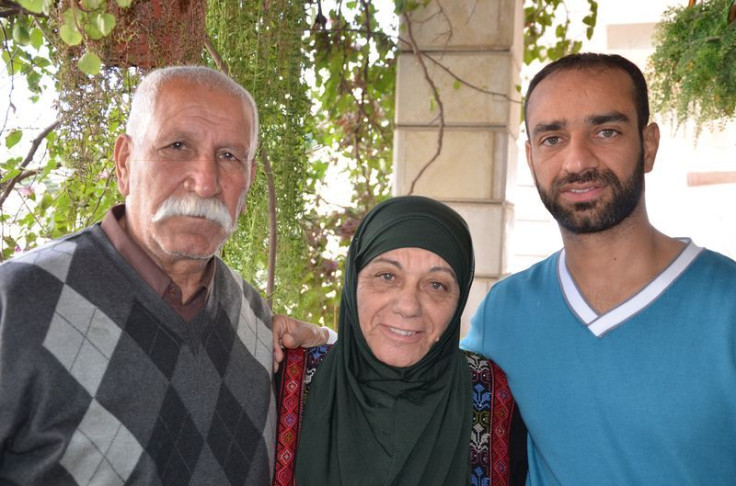

The Issawi home has been visited by sympathizers from as far away as South Africa, Germany and Korea, and the constant stream of traffic since he was discharged a week ago shows no signs of slowing. The house itself is warm and homey, making an unlikely stage for a family that Israel has characterized as one of the most notorious in the Palestinian world, with family members having been repeatedly arrested. Issawi’s parents, Tariq and Laila, and their seven children have all spent time in jail.

Three of the sons, Ra’fat, Firas and Shadi, served a combined total of 25 years in Israeli prisons; Samer – the fifth son, who is 34 – was imprisoned for nearly 10 years of his 30-year sentence after being arrested in Ramallah in 2002 during the second intifada for his alleged involvement in a series of shooting attacks against Israelis. He was discharged in 2011 along with 1,027 other Palestinian prisoners as a result of an Egypt-brokered deal between Hamas and the Israeli government for the return of Israeli Defense Force soldier Gilad Shalit, who was held captive in Gaza. A year later, Issawi was arrested again for violating the terms of his release by leaving Jerusalem and entering the West Bank. He was sent to Shita prison in northern Israel in July 2012, and faced the possibility of 20 years there; he began his nine-month hunger strike a month later, surviving solely on water fortified with vitamins and electrolytes.

Issawi is affiliated with the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine and was originally imprisoned for membership in an illegal organization, possession of explosives and firing guns at Israeli vehicles, which the Israeli courts termed attempted murder. He is banned from entering the West Bank as an administrative prisoner, which means he can be arrested and detained without trial; the Israeli government usually assigns such status to those it considers a threat to state security.

“I had no choice but to starve myself in protest of the imprisonment and wider conditions of the prisoners in Israel,” Issawi says. He adds that he reached a critical point in April 2013 when he had lost half of his body weight and doctors became worried that he would die.

“My heartbeat reached 24-28 beats per minute,” he says. “After a medical examination, the doctor told me it was getting dangerous as my heart could stop beating at any moment and I had the option of either going back to Jerusalem or dying.”

He began eating again after Israeli and Palestinian officials brokered a deal in April 2013 that allowed Issawi to serve another eight months and then be released to his home in Al-Issawiya.

Today, Issawi looks healthy, his eyes brighter than photos of him eight months ago when he was hospitalized on the brink of death. But looks are deceptive: He can still barely stomach solid food and his prolonged hunger strike caused long-term damage to his body – he tires easily and must have regular checkups on his kidneys and heart.

“My story is really nothing. There are Palestinians in Israeli prisons suffering from cancer, paralysis and many of them are dying due to the medical ignorance of the Israeli prison staff,” Issawi says.

It’s impossible to consider Issawi’s story without placing it into the context of self-starvation as a political tool. Most of the time, it’s a form of protest that garners significant publicity for a cause, although it doesn’t always speed up the resolution of a dispute. Gandhi staged prison hunger strikes in 1922, 1930, 1933 and 1942 to protest British control over India and to convince warring Hindus and Muslims to reconcile. British authorities were loath to allow him to die in their custody and they often negotiated with him during these actions. But it wasn’t until 1947 that India gained its independence.

IRA hunger striker Sands was protesting a decision in March 1976 by the British government in Northern Ireland to remove the special status of IRA prisoners. Under this change, jailed IRA members would no longer be treated like political activists but would have to wear prison garb and do prison work like common criminals. Their extra visits and food parcels would also be eliminated. Although Sands was elected to the British Parliament during his 66-day hunger strike and his death brought protests throughout the world supporting the Irish republican movement, conditions at Maze Prison didn’t change.

Issawi’s hunger strike lasted longer than most. Whether he intended to follow through is open for debate – his consumption of fortified water could be seen as a way to avoid death or to lengthen his strike. In any event, he is lucky to be alive. A person can die of malnutrition in six to eight weeks, or two weeks without water. After a month of fasting, the risk of organ failure rapidly increases.

Issawi says he drew inspiration from Nelson Mandela and was intent on ensuring the release of Palestinians who have been imprisoned for as long as 34 years. “Leaders from around the world attended Nelson Mandela’s funeral because they recognized the rights of the people in South Africa,” Issawi says. “There should be a recognition of our rights, the rights of over 5,000 prisoners, many who are children, women and the elderly.”

His sister Shireen says it was difficult for her family to see Samer slowly starve himself, but ultimately, “We were very proud of his hunger strike, because his demands were not just for him; it was for all the prisoners -- many of the prisoners who were released as part of the Gilad Shalit deal were imprisoned again,” she says. “But we were very worried about his life. International law says it’s our right to oppose this occupation. We hope that one day we will live in peace.”

Issawi got out of prison a week ahead of 26 other Palestinian prisoners, among a total of 104 who are being released as part of an agreement brokered by the United States in the hopes of reinvigorating peace talks between Palestine and Israel (the final group of five prisoners is expected to be let out at the end of March 2014; on Monday night the Israeli High Court rejected a petition to block their release). All prisoners were charged and imprisoned prior to the signing of the Oslo Accords in 1993 and were serving sentences of between 19 and 28 years. Though Issawi was not one of the 26 whose release was negotiated, pro-Israel groups – and Samer’s sister, for that matter – have lumped the two together.

At a protest that coincided with the Issawi household celebration, Lizi Hameira, 38, of Tel Aviv, told IBTimes she opposes the release of all Palestinian prisoners. “The story of Issawi is the climax of absurd,” she said. “He was released during the Shalit deal and he returned to terror. He was arrested again and because of a hunger strike a judge allowed him to be released last week. The first thing Issawi did was be filmed being released saying at his welcome reception that Israeli soldiers should be kidnapped.”

Families of the victims killed by the 26 men released in the early hours of Dec. 31 marched from outside Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s residence to the Western Wall in the Old City of Jerusalem. Some of the Palestinians were convicted of torturing, strangling or stabbing Israeli civilians to death.

Meir Indor, head of the Almagor Terror Victims Association, who opposes the release of the 26 prisoners, told IBTimes that if Israel wants peace, it needs the backing of the public, and releasing Palestinian prisoners is not the way to achieve it.

“Who is more suited to speak on the issue of Palestinian prisoner release than the victims of terror, who feel they’ve sacrificed so much, and the justice system has collapsed around them?” Indor asked. “When you’re dealing with terrorism, you need the voice of the nation. The voice of the nation is today the voice of the victim, because the nation identifies with the victims, the families.”

Almagor members have been protesting outside Netanyahu’s residence in Jerusalem for more than a week and have erected a tent occupied by up to 50 people who arrive in shifts to hand out fliers and hold placards.

When IBT visited the protest site, Netanyahu’s car pulled up along a back street flanked by two police cars. The small group of protesters snapped into action at the guarded barrier before the residence, chanting, “Titbayesh,” which means “Shame on you” in Hebrew, and waving placards with hands dyed blood-red.

Netanyahu did not speak with the protestors or get out of his car in their sight.

One of the Almagor members, Ortal Tamam, 25, was specifically protesting the release of four men convicted of the murder of her uncle, Moshe Tamam, in 1984. “These men are cold-blooded murderers and they have blood on their hands,” she said. “The public do not support their release.”

Washington has hailed the release as a “positive step” in the peace process between Israel and Palestine. U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry was in Israel on Jan. 2 to further set out the framework for the fragile peace talks between Israel and Palestine.

Of the 26 Palestinian prisoners, 18 left Ofer prison for Ramallah early Tuesday morning. Three others were taken to the Gaza Strip. The remaining five were driven from Ofer to Israeli-annexed East Jerusalem, arriving by 2:30 a.m. on Tuesday.

The 18 who reached Ramallah were welcomed by Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas in his presidential compound, before flowers were laid on the grave of the late Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat.

Despite his personal success, Issawi says he has little hope for the resumption of peace negotiations brought about by the releases, which coincided with expanding Israeli settlements in the West Bank.

“The negotiations are useless; they aren’t doing anything,” he says. “They are demolishing houses, taking out Palestinian trees and building continuous settlements. This is a sign there will not be peace between them in the near future. The occupation does not want peace.”

He acknowledged, however, that his hunger strike did result in his early release, if nothing else. And on this particular morning, an elderly Palestinian woman whom the family did not know arrived to congratulate him, saying, “All the birds in the sky are happy for you.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.