Europe's Refugee Crisis: Why Millions Of Migrants Are Just What Europe Needs

As successive waves of refugees from the Middle East and Africa stream into Europe, some leaders are asking whether their countries can afford the influx. “How many refugees can a society bear?” asked Alexander Gauland, the head of a German party that opposes taking in migrants.

Gauland joined a growing chorus of politicians arguing that Europe’s economies will groan under the weight of new arrivals from war-torn states like Syria and Afghanistan.

But economists and migration experts say the immediate economic impact, though substantial, shouldn’t dissuade European governments from pursuing a vigorous response to the unfolding crisis. In fact, with the broader European economy's aging workforce and ample demand for labor, young workers of wide-ranging skill levels could prove a long-term boon.

“If you compare the costs to Europe's GDP, it’s really not a significant amount of money," says Simond DeGalbert, a visiting fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington. “The more we resist doing what’s necessary to make sure these people can settle, the more significant the costs will be in the long term.”

Though Europe is hardly on firm economic footing, experts say efforts to house and integrate the refugees now will determine the fiscal effects down the road -- and could eventually prove a net gain to European budgets.

Positive Contribution

Of course, throngs of desperate refugees -- whether wading ashore on Greek islands, marching across the Hungarian countryside or scrambling for seats aboard trains to Germany -- will mean sizable humanitarian bills for local and national governments.

German officials have put the immediate tab of caring for refugees at nearly $14,000 per head. Last year, Germany spent $2.7 billion housing, feeding and clothing some 203,000 migrants; the cost of accepting as many as 800,000 migrants this year is estimated to rise to $11 billion.

Those numbers may seem large, but they pale next to Germany’s $3.8 trillion GDP -- a per-capita national production four-and-a-half times that of Lebanon, which has taken in 1.2 million Syrian refugees.

And rough estimations as to the immediate costs, says DeGalbert, might simply serve to inflame anti-immigrant extremists. “One needs to be very careful about this evaluation given the sensitivity of the topic,” DeGalbert cautions.

But in the longer term, an array of research indicates that expenditures on immigrants are more than balanced out by tax contributions. Carlos Vargas-Silva, an economist at the University of Oxford, says that while there’s likely to be a short-term economic burden, immigrants tend to pay more in taxes than they receive in benefits like welfare.

“What we know about refugees is that they are young,” Vargas-Silva says. “That person is going to start paying taxes over time. The net contribution is likely to be positive given how young they are.”

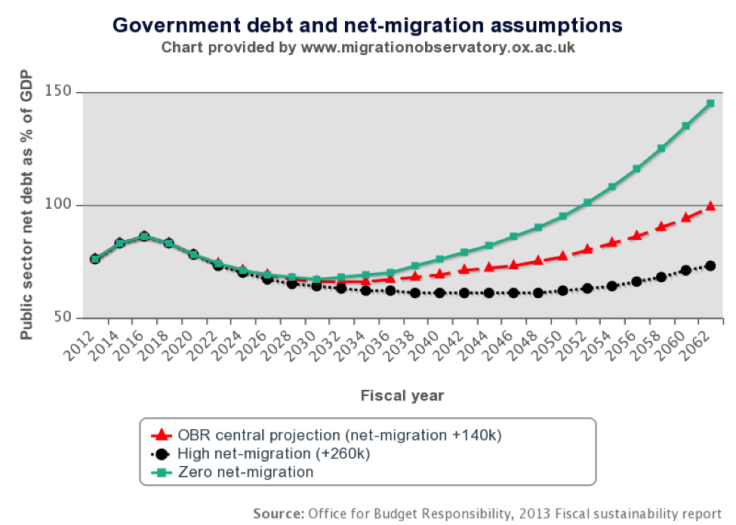

Vargas-Silva penned a report in March outlining the fiscal effects migrants were expected to have on the British economy over time. The analysis found that a high-immigration scenario -- more than 260,000 migrants -- could halve the U.K.’s public debt over 50 years.

A study this month from the International Labor Organization, underwritten by the OECD and the World Bank, concluded that “in most countries migrants pay more in taxes and social contributions than they receive, and contribute substantially to destination countries’ economies.”

Yet as the U.K.’s Royal Economic Society has pointed out, these findings defy public perceptions. According to a 2008 survey, 44 percent of European citizens thought, inaccurately, that migrants drain more from public funds than they contribute.

According to Demetrios Papademetriou, president of the Migration Policy Institute Europe, those longer-term economic considerations get eclipsed during the chaos of humanitarian calamity. “This is the necessary second-order thinking that no one has the time to pay attention to when a crisis is unfolding,” Papademetriou says.

In fact, many European states could use an infusion of migrants. More than a fifth of the population in Germany, Italy and Greece is over 65 years old, and that proportion is rising. Young migrants who file into the workforce promise to keep pension funds afloat and tax coffers full.

And the image some have of migrants as uniformly poor and unskilled also misses the mark. “We often assume that these are people from miserable backgrounds. In reality they bring lots of human capital assets with them,” Papademetriou says.

In Germany, with a job vacancy rate around 3 percent, there are ample positions to fill.

And regardless of refugees’ education and skill levels, says Vargas-Silva, they generally arrive ready for the labor force. “Crossing the Mediterranean, you have to be young, you have to be in a certain physical condition,” he explains. “People that get to Europe are people that can contribute to the system.”

"On The Verge Of Explosion"

The ability of refugees to contribute, however, depends on having a working system to begin with. In Europe, that’s no guarantee. Germany has perhaps the most developed refugee settlement apparatus in the European Union, with Labor Ministry integration and apprenticeship programs tailored to bring young workers into companies looking for able hands. Since 2014, government talent scouts have scoured refugee populations for skilled workers to match with employers immediately.

Even in Germany, however, the initiatives could buckle under the unexpected volume of refugees. New arrivals face not only the usual challenges of integration, including language and cultural barriers, but a rising tide of anti-immigrant violence and hate speech.

Papademetriou says Germans will have to be patient for refugees to integrate into the economy. "In a perfect world it would be about three years. In a German world it would be between three to five years,” he estimates.

But not every country is Germany. “If we’re talking about some of the Eastern European countries, it could be never,” Papademetriou says.

Far from extending integration initiatives, other European states have thrown up barriers. Slovakia’s government announced that it would only take in Christians, while Hungary is planning to build a fence to keep out immigrants. In Denmark and Sweden, right-wing factions opposed to settling refugees are ascendant -- in the latter case, a party with neo-Nazi roots recently commanded a plurality of Swedish citizens in a national poll.

Other countries simply lack Germany’s wealth. Greece, which has seen some 150,000 refugees land on its shores this year, according to the International Organization for Migration, only just survived an economically devastating standoff with the eurozone over its debt crisis and is still a financial basket case.

Now Greek authorities are stretched thin. On the island of Lesbos, which Greece’s migration minister said was “on the verge of explosion,” the Greek army planned to begin baking loaves of bread to feed the seemingly endless flow of refugees.

Papademetriou points out that even if Greece or other struggling economies wished to take out bonds and invest in the incoming refugees, they’re at a disadvantage to Germany, whose government can borrow at one of the lowest interest rates in the world. Greece’s long-term borrowing rate is well over 10 times that of northern countries like Austria and even Latvia.

To ameliorate the disparities, the European Union has proposed measures to tackle the crisis, setting up refugee quotas based on nations’ economic production, total population and unemployment rates.

But even with refugees fairly allotted, it will remain the responsibility of individual nations to do the hard work of integrating them into their societies, says Papademetriou. “After the emergency, that’s when the real issues begin.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.