ExoMars Mission To Find Life On Mars Needs Another $430 Million To Make Its 2020 Journey

Days after scientists from the European Space Agency announced a computer glitch was responsible for the crash of a demonstration probe that was supposed to land on the surface of Mars, ministers from EU countries will meet in Lucerne, Switzerland, next week to decide whether to give ESA’ ExoMars mission another 400 million euros ($430 million) of funding.

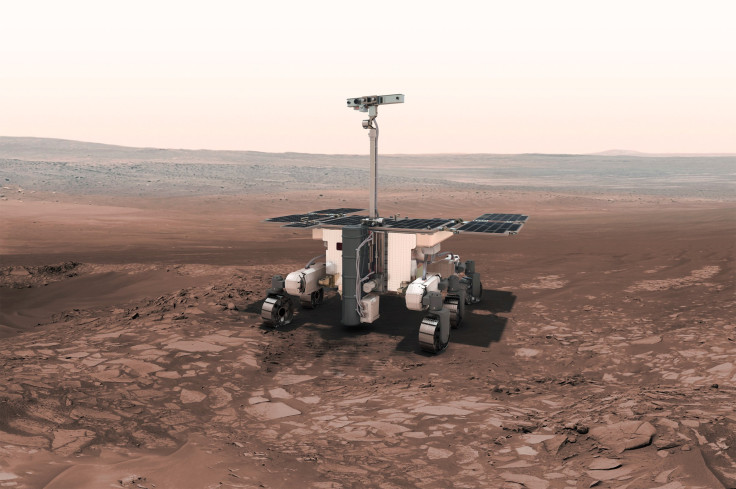

ESA needs the money to finish building the ExoMars rover which is scheduled to launch aboard a Russian rocket in August 2020. The rover, which will take about nine months to get to the red planet, is being designed to drill up to 2 meters (almost 7 feet) below the Martian surface to search for microbial activity or other traces of life, both past and present. Looking underground is important because the Martian atmosphere is too harsh for life as we know it to survive above surface.

A demonstration of the ExoMars rover’s landing was supposed to be made in the first phase of the mission, which successfully launched a satellite in orbit around the planet to study Martian atmosphere. But the Schiaparelli probe that was supposed to land on Mars crashed into the surface instead. ESA scientists, however, said they learnt a lot from the failure and said that a software glitch was easier to fix than a hardware problem.

“We will have learned much from Schiaparelli that will directly contribute to the second ExoMars mission being developed with our international partners for launch in 2020,” David Parker, ESA’s director of human spaceflight and robot exploration, said Thursday.

ExoMars was initially scheduled for a 2018 launch, and funding concerns have already pushed that date by 2 years. Ministers from 23 countries (including Canada, which gives financial support to ESA programs) will meet in Lucerne on Dec. 1-2 to discuss the additional funding required by the mission.

“The rover remains scientifically compelling because there is no other mission planned to go below the surface of Mars which is damaged by radiation and which would destroy any past or present life,” Parker told BBC News.

The search for life on our neighboring planet has seen a lot of work in recent years, especially since we discovered water (mostly frozen) on Mars. NASA recently devised an instrument that can use smell to sniff out life on the planet.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.