Exploring Venus With Venera-D: NASA, Russia’s Space Research Institute Working Together On Mission Objectives

Even though it is the most similar planet to Earth in composition and size, and being the closest, Venus has not been studied nearly enough by astronomers. The main deterrent to scientific missions is the extremely harsh environment on the planet, with clouds of sulfuric acid and near-surface temperatures of about 470 degrees Celsius (almost 880 degrees Fahrenheit).

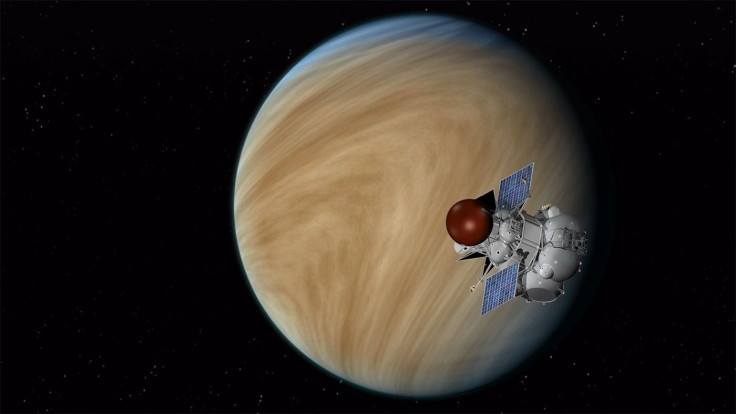

Only some probes of the Venera missions, launched by the erstwhile Soviet Union, have ever made it through to the surface of Venus, even beaming back images and other data, before being destroyed by the inclement conditions on our so-called twin planet. But now, scientists from the Russian Academy of Sciences’ Space Research Institute (IKI) are gearing up for Venera-D — the latest mission in the Venera series. And this time, NASA is working with IKI on the mission’s science objectives.

Scientists sponsored by NASA are meeting their counterparts at IKI this week (March 14-16) to discuss and fine-tune the objectives of the latter’s Venera-D mission. As currently envisaged, the mission will have an orbiter that would operate for up to three years above the Venutian atmosphere, as well as a lander which would survive on the surface for a few hours. There may also be a solar-powered airship that will independently explore Venus’ upper atmosphere for up to three months.

Read: Beating The Heat On Venus For Longer Surface Missions

“While Venus is known as our ‘sister planet,’ we have much to learn, including whether it may have once had oceans and harbored life. By understanding the processes at work at Venus and Mars, we will have a more complete picture about how terrestrial planets evolve over time and obtain insight into the Earth’s past, present and future,” Jim Green, director of the Planetary Science Division at NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C., said in a statement Friday.

A joint science definition team, made up of researchers from IKI and NASA, along with other NASA-sponsored scientists, submitted its report to both NASA and IKI headquarters earlier this year.

“On a solar-system scale, Earth and Venus are very close together and of similar size and makeup. Among the goals that we would like to see if we can accomplish with such a potential partnership is to understand how Venus’ climate operates so as to understand the mechanism that has given rise to the rampant greenhouse effect we see today,” David Senske, co-chair of the U.S. Venera-D science definition team, and a scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, said in the statement.

The landing site for the surface lander will be decided based on data collected by NASA’s Magellan mission of 1990, which used a radar to map 98 percent of the planet with a resolution of up to 100 meters (330 feet), IKI said in a statement Monday (in Russian). The statement added the mission will likely be launched in 2026-27.

Venera, the Russian name for Venus, was active between 1961 and 1984, and a total of 16 missions saw 10 probes successfully land on Venus, marking the first time a human-made object landed on another planet as well as the first instance of interplanetary communication.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.