'False Positive': These Exoplanets Are Actually Stars

KEY POINTS

- Researchers determined three previously validated exoplanets to actually be stars

- Another one may have also been misclassified as a planet

- The objects are larger than Jupiter, which is unusual for a planet

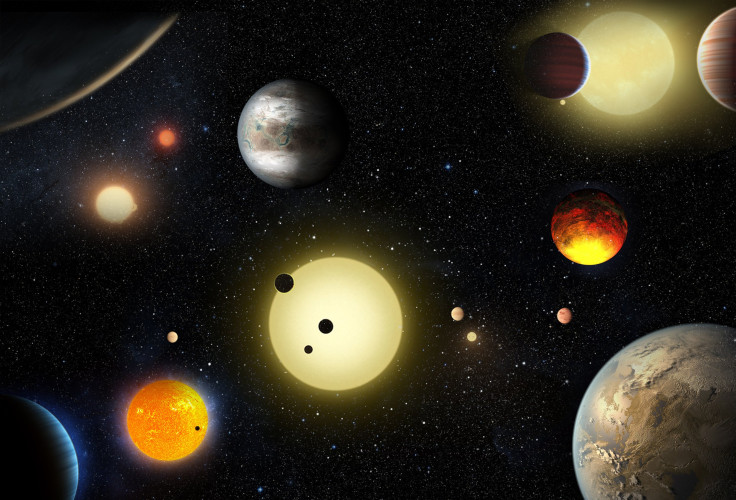

Thousands of exoplanets have been discovered, but researchers now learned that several of them aren't actually planets. Using updated measurement methods, they found that the objects are actually stars.

Exoplanets are the planets outside our solar system, whether free-floating or orbiting a star. Thousands of them have been discovered since they were first spotted in the 1990s. So far, almost 5,000 exoplanets have been confirmed, while 5,000 more are planetary candidates, or the ones that may be planets but haven't been confirmed, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) noted.

Initially, the team of researchers behind the study, published Wednesday in the Astronomical Journal, wasn't really searching for "planetary false alarms." Instead, they were looking for systems that have a tidal distortion in the data from NASA's Kepler Space Telescope, MIT noted.

However, the team noticed that one of the objects, Kepler-854 b, had a rather odd signal that was too huge to be that of a planet.

"Most exoplanets are Jupiter-sized or much smaller. Twice [the size of] Jupiter is already suspicious," Prajwal Niraula of MIT, study first author, said in the university news release. "Larger than that cannot be a planet, which is what we found."

Kepler-854 b was discovered in 2016 via transit detection, or by the "dip" in starlight as an object passes in front of a star. At the time of its discovery, however, the means that astronomers used to measure planets were not as precise as the ones used today, and Kepler-854 b was deemed to have a normal size of a planet, MIT noted.

However, the researchers' recalculation determined that Kepler-854 b is actually three times the size of Jupiter. The team confirmed that Kepler-854 b isn't really a planet but is, in fact, a star orbiting a larger host star. After scouring the Kepler data for other such false alarms, the researchers found a few more.

"(T)hree statistically validated transiting planets, Kepler-854 b, Kepler-840 b, and Kepler-699 b cannot be planets but are instead small stars," the researchers wrote. "In addition, we demonstrated that a fourth statistically validated planet, Kepler-747 b, has a somewhat larger radius than other confirmed gas-giant planets with the same stellar irradiation level, suggesting that it too is not a planet, but a small star."

This updates the current list of exoplanets, reducing it by at least three, with Kepler-747 b signifying another object possibly misidentified as a planet. According to the researchers, their work shows the importance of more accurate parameters in validating exoplanets. For their work, for instance, they used the measurements by European Space Agency's Gaia mission, which is said to provide the most accurate measurements so far but was not available during the Kepler mission.

"Some of the lessons learned in this work will help improve statistical validation techniques, which will, in turn, support more accurate studies of planet demographics," the researchers wrote.

"This is a tiny correction," Avi Shporer of MIT, study co-author, said in the news release. "It comes from the better understanding of stars, which is only improving all the time. So, the chances of a star's radius being so incorrect are much smaller. These misclassifications are not going to happen many times more."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.