Fed To Unveil Another Big Rate Hike As Signs Of Economic Slowdown Grow

With the Federal Reserve expected to hike its key interest rate by three-quarters of a percentage point on Wednesday to battle high inflation, focus will shift to how deeply signs of an economic slowdown have registered with its policymakers.

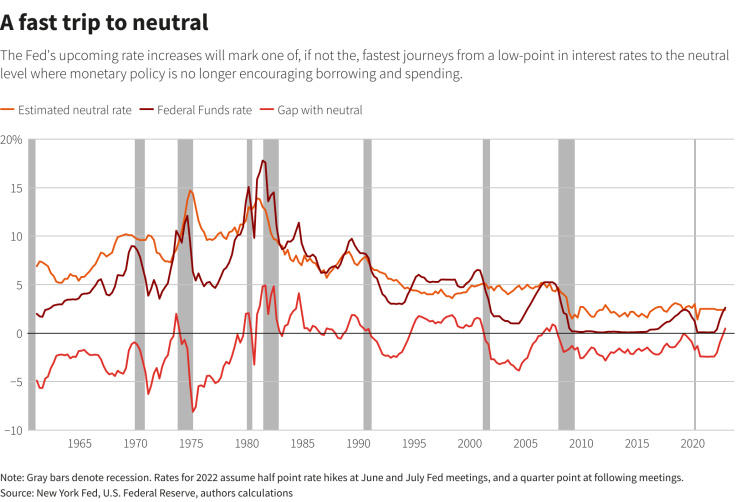

The anticipated increase in the target federal funds rate, the Fed's key tool in trying to lower inflation from a four-decade high, will bring the U.S. central bank to a mile marker of sorts as it reaches a level of around 2.4% that is estimated to no longer encourage economic activity.

That will represent one of the fastest-ever gear changes in U.S. monetary policy - just over four months ago the policy rate was near zero and the Fed was buying billions of dollars of bonds each month to help the economy recover from the COVID-19 pandemic.

A fast trip to neutral:

But while there has been little progress registered yet in the inflation fight, signs of economic stress are accumulating - and raising the stakes for Fed officials as they weigh just how much tighter monetary policy needs to be to slow price increases against the risk that going too far could trigger a recession.

Even ahead of this week's two-day policy meeting, the inflation problem was considered so dire that investors placed about a one-in-four chance the Fed would surprise markets with a larger 1-percentage-point increase in its benchmark overnight interest rate, reminiscent of the hikes used in the early 1980s by then-Fed Chair Paul Volcker.

As the Fed's impact on the economy becomes more apparent, the issue now is whether it is at risk of overdoing it.

Parts of the U.S. bond market are signaling an increased likelihood of recession, with yields on 2-year U.S. Treasury notes now higher than they are for 10-year Treasuries, a possible sign of lost faith in near-term economic growth and reflecting a possibility the Fed may be forced to cut rates within a relatively short span of time.

Fears of a stalling economy were stoked late on Monday when Walmart Inc, whose massive footprint offers a broad view of consumer behavior, cut its profit outlook and said inflation had pressed shoppers to spend their money on food and fuel instead of higher-margin discretionary items like electronics and apparel. General Motors Co, for its part, said it had eased hiring and delayed planned spending in response to inflation and to hedge against a possible broader slowdown.

The U.S. Commerce Department is expected on Thursday to report that gross domestic product grew at a turgid pace in the second quarter. New employment data scheduled to be released next week will show whether robust job creation, considered an important strength of the U.S. economy right now, continued in July.

CONFLICTING DATA

Fed policymakers will not issue new economic projections of their own on Wednesday. But a new policy statement due to be released at 2 p.m. EDT (1800 GMT) and Fed Chair Jerome Powell's news conference half an hour later should elaborate on how the central bank views the recent economic data and at least hint at its next steps.

That will almost certainly include another interest rate increase at the Fed's next policy meeting in September, with upcoming inflation data likely to shape whether officials opt for another 75-basis-point increase, or scale back to a half-percentage-point move.

With consumer prices rising at a more than a 9% annual rate as of June, "the Fed will not slow the pace of hikes until they are convinced inflation has turned," Ian Shepherdson, chief economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, wrote recently.

A number of Fed officials at various points since the start of the year have said they thought inflation had peaked, only to be caught out as prices continued to rise faster. By the Fed's preferred measure, inflation is running at more than three times the central bank's 2% annual target, leaving policymakers aligned behind not just the unusually large 75-basis-point hikes - the biggest moves since 1994 - but a promise to continue raising borrowing costs until monthly inflation numbers fall.

To some economists that has heightened the risk of error, since data on prices may lag the impact of rising rates on the economy and prompt the Fed to continue its monetary policy tightening in the midst of a slowdown.

The average contract rate on a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage has risen from below 3% to about 5.5% on the basis of the Fed's rate hikes so far, for example, and new home sales already have fallen to the lowest levels since the start of the pandemic.

By the time of the Fed's Sept. 20-21 meeting, policymakers will have two months of additional data in hand on prices, consumer spending, business output, jobs, and other aspects of the economy.

If inflation does slow before that meeting, it could clear the way for the Fed to slow down.

Investors, as of now, are roughly split over whether that will happen, with data likely to continue pulling in both directions.

The U.S. economy "is likely to have contracted in the first half of the year, but job growth remains robust. Inflation is leading to record-low consumer sentiment, but consumers are still spending," as are businesses, Greg Daco, chief economist at EY-Parthenon, wrote this week. The U.S. right now is "a world of paradox."

© Copyright Thomson Reuters {{Year}}. All rights reserved.