As Ferguson Violence Continues, Federal Intervention Looms

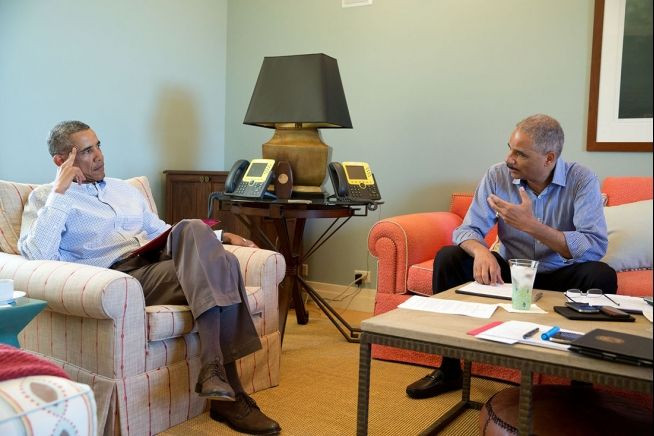

President Obama met with Attorney General Eric Holder Monday to discuss a possible federal response to the violence plaguing Ferguson, Missouri, sparked by the shooting death of an unarmed black youth that has produced more than a week of rioting. Though Missouri Gov. Jay Nixon has already declared a state of emergency, declared early morning curfews for two days and called in the National Guard, the violence has continued to intensify, raising questions about what the federal government can and should do to quell the unrest.

“It’s theoretically possible that the federal government could take over fully, but it’s a fairly unlikely scenario right now,” said Timothy Lynch, the director of the project on Criminal Justice at the CATO Institute, who added local authorities seemed to welcome input from the Justice Department.

To aid an end to the violence, Holder has assembled a team of advisers to assist Ferguson police. “[We] will be dispatching additional representatives from the Community Relations Service, including Director Grande Lum, to Ferguson,” Holder said. “These officials will continue to convene stakeholders whose cooperation is critical to keeping the peace.”

Nixon has already brought in state police to help manage the situation after local and county police were heavily criticized for using riot gear, tear gas and heavy artillery, which only served to intensify the anger of protesters.

“I’ve asked them, tell me what to do and I’ll do it,” said Ferguson police chief Thomas Jackson, who also said he welcomed the Justice Department’s training on racial relations in the suburb where two-thirds of the 21,000 residents are black and all but three of the police force's 53 officers are white.

Should the situation worsen, the federal government has a number of options available, Lynch said. The easiest is that the National Guard could be federalized, shifting command of the National Guard from the state to the federal government.

Precedent for regular military action was seen in 1992 when active duty Army soldiers and Marines were called in to bring the Los Angeles riots under control. The racially charged riots, which came after the police officers who beat Rodney King were acquitted, resulted in more than 11,000 arrests, 2,000 injuries and 53 deaths.

However, Charles Stimson, manager of the National Security Law Program and a senior legal fellow, a Heritage Foundation expert and former federal prosecutor, said the closer "you get to deploying the National Guard in any situation, the closer you get to the federal government being more involved.”

But judging when that moment comes is far more difficult. The LA riots, for example, saw unprecedented levels of murder, violence and vandalism that made the federal intervention for more obvious.

Ferguson, Stimson said, is far more difficult to call. “I think the tipping point is based on volume and scale. Volume of the emotions, the disruption, noise, energy and scale of how deeply this affects the country and any civil rights movements it awakens.”

Stimson says if the federal government wants to intervene in a big way it would have to establish jurisdiction. That point comes if the Justice Department has a federal nexus: a civil rights violation, for example, or crimes that cross state lines,” said Stimson. “We’re not talking about Marines coming over a hill, but assistance could come in the form of a helicopter or some sort of aircraft to use to observe.”

Other federal options, such as replacing local police would be unprecedented, Lynch said. “That is a much more delicate and complex situation because policing in the U.S. is primarily a state and local responsibility,” he said. “The only exception is if the federal government concludes that the state government is not just not doing its job, like enforcing the law, but affirmatively going out and committing crimes themselves or blatant violations of constitutional rights, then there is an avenue for the federal government to intervene, but that’s quite rare.”

Once the riots in Ferguson are over, a federal intervention of a different sort is far more likely. The state or local government could ask the Department of Justice for a federal monitor to offer input and advice on the police department as part of a consent decree, Lynch said. Such legal agreements usually are reserved for police departments suffering from rampant corruption and require serious oversight. New Orleans accepted a consent decree in 2012 after a spate of post-Katrina police violence undermined the department’s ability to administer justice. Similarly, the Los Angeles Police Department entered into a civil rights consent decree in 2001.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.