Fossil Of Ancient Stick Insect That Could Camouflage Itself To Look Like Plant Life Discovered In China

An international team of scientists have discovered the fossil of an ancient stick insect, which lived 126 million years ago and mimicked the appearance of a nearby plant.

According to scientists, the species, called Cretophasmomima melanogramma, is the oldest-known stick insect to use such camouflage capability. The fossil was discovered in Liaoning province in northeastern China, which is part of the Jehol rock formation that houses many fossils, including those of early birds and feathered dinosaurs.

“Cretophasmomima melanogramma is one of the grand-cousins of today's stick and leaf insects,” paleontologist Olivier Béthoux of the Center for Research on Paleobiodiversity and Paleoenvironments (CR2P) at the National Museum of Natural History in Paris, and one of the researchers, told Reuters.

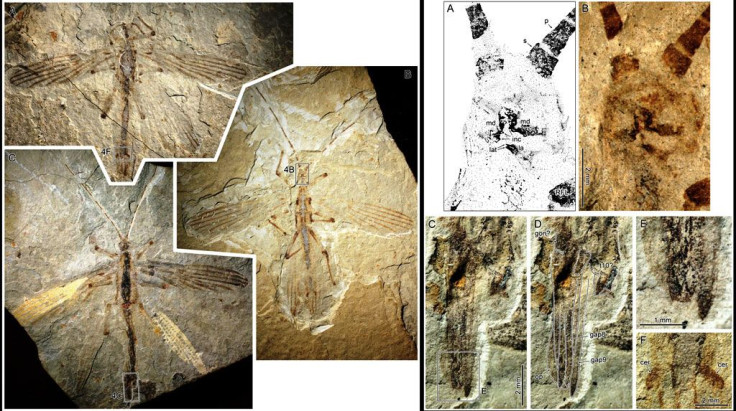

The researchers said in a study, published in the journal PLOS ONE on Wednesday, that the ancient creature likely used its leaf-like appearance to hide from tree-climbing predators that fed on insects. According to the scientists, they have discovered specimens of Cretophasmomima melanogramma -- one female and two males -- with adaptive features to help them take on the look of a plant recovered from the same area.

The scientists, using information from the fossil, said that the insect sported wings with parallel dark lines that likely produced a tongue-like shape to hide its abdomen whenever the bug was in a resting position.

The scientists also found a distant relative of the Gingko plant, called Membranifolia admirabilis, with pale leaves and similar dark-veined lines running through it. According to scientists, the insect used this plant as a model for its disguise.

While none of the original pigmentation remained on the fossil, the insect is believed to have once been green or dark yellow in color with dark-purple lines running through it, scientists said, adding that females of the species were estimated at about 2.2 inches long, while the males were a bit smaller.

Based on the discovery, scientists have concluded that leaf mimicry was a defensive strategy for some insects as early as in the Early Cretaceous period. However, additional refinements characteristic of recent forms, such as using a curved part of the forelegs to hide the head, were still lacking.

“This new record suggests that leaf mimicry predated the appearance of twig and bark mimicry in phasmatodeans. Additionally, it complements our growing knowledge of the early attempts of insects to mimic plant parts,” the scientists said in the study.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.