Human Ancestors Who Lived 4 Million Years Ago Had Pretty Similar Skulls

A group of researchers analyzing the fossils of our early ancestors has found that some of our long-dead relatives were more similar to us than previously thought.

It has long been believed that humans witnessed a series of evolutions over millions of years to become the intelligent species we are. The idea has been supported by a range of remains from different periods, but when scientists from the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg examined skull fossil of an early hominin, who lived some four million years ago, they were totally surprised.

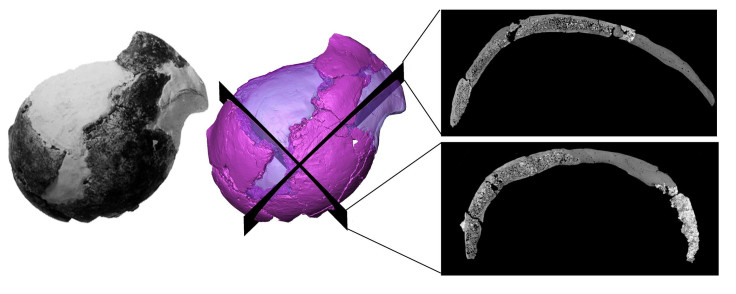

The team found that the thick cranium of the specimen – belonging to an extinct group called Australopithecus – was composed of a long spongy bone, which was very similar to that found in present-day humans.

"This large portion of spongy bone, also found in our own cranium, may indicate that blood flow in the brain of Australopithecus may have been comparable to us, and/or that the braincase had an important role in the protection of the evolving brain," Amelie Beaudet, the lead author of the study, said in a statement.

The four-million-year-old fossil of the specimen in question was unearthed more than two decades ago in the Jacovec Cavern near Johannesburg, providing the earliest evidence of human evolution on the continent. However, as the cranium was highly fragmented and not so well preserved, scientists were not able to delve into the anatomy of the skull or the identity of the person in question.

Beaudet and colleagues solved this problem by employing high-resolution imaging techniques in "virtual paleontology" to take fresh scans of the specimen. Their technique worked and they were able to explore the inner anatomy of the specimen in unprecedented detail and report the bone similarity – a feature that was not been seen before.

The revolutionary discovery got even more interesting when the team compared the restructured braincase with that of other modern-human ancestors. Specifically, they studied an ancient hominin called Paranthropus, who lived some two million years ago, and found that its cranium was much thinner and composed of a compact bone, rather than spongy one. This, as the researchers explained, hints at a different biology in our early relatives.

Jacovec cranium represents a unique opportunity to learn more about the biology and diversity of our ancestors and their relatives and, ultimately, about their evolution,” Beaudet added in the statement. In fact, sophisticated imaging techniques like these could open unique perspectives to examine the entire fossil assemblage from South Africa and provide critical insight into our long-dead relatives.

The study titled “Cranial vault thickness variation and inner structural organization in the StW 578 hominin cranium from Jacovec Cavern, South Africa” was published in the Journal of Human Evolution.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.