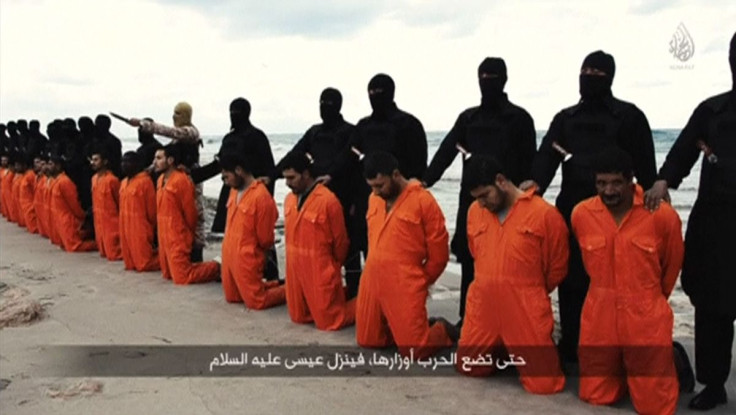

ISIS Rome Is Next: Now That Islamic State Is In Libya, Will Italy Become A Breeding Ground For Extremists?

As the Islamic State group expands its reach into Libya, the group also known as ISIS sits on the doorstep of a nation that has one of the largest Muslim populations in Europe: Italy. The militant group threatened to seize Rome in a video released this week showing the beheadings of 21 Coptic Christians from Egypt in Libya. Although the number of foreign fighters from Italy operating in Iraq and Syria, where ISIS has established its so-called caliphate, is on the lower end among Western European nations, Islamic extremism in Italy may grow as ISIS makes an effort to recruit in the country.

"I would predict that [extremism] will rise not only because of Libya, but because of the proximity to Tunisia, which is the single largest source of foreign fighters," said Tom Sanderson, co-director and senior fellow of the Transnational Threats Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a nonpartisan think tank based in Washington, D.C. There are estimated to be 1,500 to 3,000 foreign fighters from Tunisia fighting in Iraq and Syria, according to the latest numbers from the International Center for the Study of Radicalization and Political Violence. Libya is located 109 miles south of the Italian island of Lampedusa and 300 miles south of Sicily.

ISIS could use its foreign fighters from Italy, Libya or Tunisia to launch an attack against Italy, but the likelier scenario is the Islamic State inspiring a radical Muslim within Italy to commit a terrorist act, which was the same modus operandi as the French brothers who attacked the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo in Paris in January, according to Sanderson. "ISIS does not have to send a team from Libya to Vatican City or Rome to conduct an attack," he said. "They can ignite individuals who are already there."

The threat outlined in the video -- “we will conquer Rome, by Allah’s permission” -- isn’t the first time the Islamic State group put Italy in its crosshairs, but the militant organization is much closer now to Italy’s shores than it was when it superimposed images of the ISIS flag flying over St. Peter’s Square in its magazine, Dabiq, in October. ISIS also doesn’t have a large contingent of foreign fighters from Italy. There are only 80 Italians fighting in Iraq and Syria, and that number includes militant groups other than the Islamic State. Those 80 fighters pale in comparison with the 1,200 suspected foreign fighters from France, 600 from the United Kingdom and up to 600 from Germany.

Italy, whose 2.2 million Muslims make it the fourth-largest Muslim population in Europe, has the highest percentage of citizens with an unfavorable view of Muslims, according to a Pew Research Center poll conducted last spring. Italy also is seeing a surge in the number of migrants reaching its shores because of the unraveling security situation in Libya, its former colony -- which is fueling anti-Muslim resentment among people who say immigration is a problem. And this week, the principal of a high school in northeastern Italy banned veils for his students “to avoid racism and provocation” after an Egyptian student was attacked, according to local media reports.

Italy’s foreign minister sounded the alarm Wednesday on the possibility of ISIS using Libya as a base to attack Europe. "There is an evident risk of an alliance being forged between local groups and Daesh and it is a situation that has to be monitored with maximum attention," Paolo Gentiloni told Italy’s parliament, using an alternative name for the Islamic State. "We find ourselves facing a country [Libya] with a vast territory and failed institutions, and that has potentially grave consequences not only for us but for the stability and sustainability of the transition processes in neighboring African states. The time at our disposal is not infinite and is in danger of running out soon,” he said.

Anti-Muslim sentiment boiled over late last year, when thousands protested in Rome following the opening of a refugee center in the suburb of Tor Sapienza. The center was taking migrants rescued as part of Mare Nostrum, the name of the massive operation to rescue migrants who fled North Africa, including many from Libya, for Europe. Mare Nostrum ended in December and was replaced with a smaller program known as the European Triton program, according to the New York Times. Those involved in the protests denied that hatred toward Muslims motivated the riots.

“We are tired of the ongoing situation of violence and terror. We are not extremists but we want to be safe in our own neighborhood and the authorities are ignoring our claims” that the migrants were behind robberies and violence in Tor Sapienza, local official Tommaso Ippoliti told the Italian Insider, an English-language newspaper in Italy.

In another sign of backlash against Muslims, a swimming pool near Milan that opened last month faced criticism from Italy’s right-wing parties for banning bikinis so the city’s growing Muslim population would feel welcome. The pool also faced protests for providing swimming courses solely for Muslim women, which critics called “reverse discrimination.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.