Kirkuk-Ceyhan Pipeline Closure Forces Kurdish Government To Diversify Economy

The main pipeline that leads from northern Iraq to Turkey is not in service because it has been damaged by fighting on the border of the two countries, officials say. Although engineers are working on repairing the pipeline, the Kurdish Regional Government in Iraq could lose millions of dollars -- money it needs to pay off its massive debt.

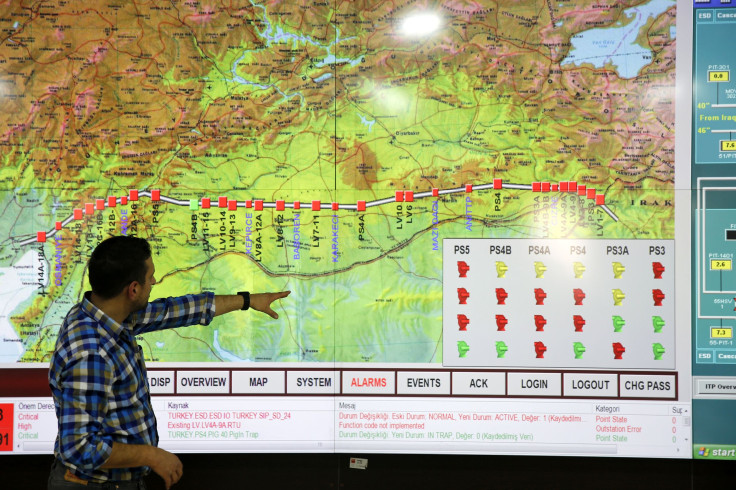

The pipeline carries some 600,000 barrels per day of crude from Iraq’s autonomous Kurdistan region to the port of Ceyhan for export. The damaged part of the pipeline is located in the southeastern part of Turkey where the government is currently fighting Kurdish militants that officials say are a part of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK). The Turkish energy ministry said it is working on the reconstruction of the pipeline, which was bombed Feb. 25, and that service should be restored soon.

“Security forces have taken necessary steps to ensure the pipeline’s safety,” the ministry said in a statement.

The pipeline is the lifeline of the Kurdish Regional Government (KRG), which is not receiving its share of the budget from Baghdad. The pipeline’s closure, even if only for a few weeks, could worsen its debt. Even without the pipeline’s closing, the KRG was struggling to make a profit, balancing the low price of oil ($30 a barrel) and its obligation to pay international oil companies. The KRG has tried to remedy the situation by starting new initiatives to diversify its economy by focusing on the agriculture and food development sectors. But until those initiatives start, the government will have to rely on its donation from the World Bank and its privatization of the electricity sector.

The KRG will need a total of $1.4 billion to stabilize its economy, the World Bank said in February. The KRG’s economy is currently not set up to bring in that amount of money without massive donations. Meanwhile, the government is dealing with a massive humanitarian crisis. Hundreds of thousands of refugees that fled the war against ISIS, some from Syria, others from cities in Iraq, are residing in Iraqi Kurdistan.

The Kurdish government has for decades wanted to establish independence from Baghdad and the fastest way it knew how to do that was by selling oil on the international market. The KRG and the central government in Baghdad agreed that Kurdistan would export 250,000 barrels of oil a day, and the disputed province of Kirkuk — now under Kurdish control — would export 300,000 barrels a day. In return, the KRG would keep 17 percent of Iraq’s budget expenditure. But Baghdad did not keep its side of the bargain. Thousands of people were employed in cities across Iraqi Kurdistan in response to the agreement and the understanding that the full budget would come through.

The KRG began exporting its discounted crude in May 2014 using its independent pipeline. Baghdad could at one point access it, but fighting and damage to the infrastructure shut the central government off.

The oil sector, and all of its transactions, were and still are overseen by the KRG, led by President Masoud Barzani. Barzani is aiming to produce 2 million barrels a day by 2019.

“The trend is toward nationalization of oil,” said Denise Natali, an expert on Kurdish oil from the National Defense University in Washington. “If you look at the KRG and what it is doing, it is gradually taking greater control of its oil production.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.