Lebanon’s Palestinian Refugees Protest Against UNRWA In Wake Of Growing Conspiracies Around Healthcare Cuts

BOURJ Al-BARAJNEH, Lebanon — Umm Aziz has not been spared the wave of fear washing over the residents of Lebanon’s Palestinian refugee camps. The 85-year-old — a refugee in a camp in Beirut’s southern suburbs for almost 70 years — has heart and kidney problems, and requires around $400 worth of lifesaving medicine a month. Up until now, her prescriptions have been covered by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), but her friends and family in the camp have told her the organization’s recent change to its refugee healthcare policy means she’ll have to cover the cost herself.

For Aziz, the recent allegations are another affliction in a tragedy-laden life. Her interview with International Business Times was overlaid by almost continuous weeping. She was pushed out of Palestine in 1948, transporting her two daughters, both under 2, in a bucket balanced on her head, to Lebanon’s southern border on foot. Some 30 years later, four of her eight sons disappeared during the infamous 1982 massacre in Lebanon’s Sabra and Shatila camps, where thousands of Palestinians and Lebanese Shiite Muslims were killed by Lebanese Christian Phalangists. Their bodies were never recovered, and three decades on, Aziz is still waiting for their return. Now, with the rumors that she will have to pay for her essential medical care, she is distraught.

“Education and medical aid are the No. 1 needs in our life, and we cannot afford them,” Aziz told IBT, drawing deeply on a skinny menthol cigarette. “If it’s not free I won’t be able to get my medicine anymore. Then what will happen to me?”

Under UNRWA’s new healthcare plan, Palestinian refugees, whose healthcare costs previously were fully covered by the refugee agency, have to cough up 20 percent of the costs for visits to private hospitals, 15 percent for care at government hospitals and 5 percent at medical facilities run by the International Committee of the Red Cross. The additional funds accrued by UNRWA will be used to treat people with stays in intensive-care units as well as those with long-term illnesses such as cancer and heart disease. However, medicinal costs are unchanged — Aziz will still receive her prescriptions free of charge. But she doesn’t know that, thanks to an orchestrated campaign of misinformation by popular Palestinian factions Fatah and Hamas, to drum up political support

Zizette Darkazally, senior communications adviser and public information officer for UNRWA’s Lebanon branch, said in an interview with IBT: “[Palestinian] groups portrayed [the healthcare changes] in a bigger context … using inflammatory words like intifada [the Arabic word for uprising] and telling people, ‘UNRWA is going to disappear.’”

Around 450,000 Palestinians live in Lebanon's 12 Palestinian refugee settlements, more than 10 percent of whom fled similar camps in Syria since the start of the conflict in 2011. The camps’ residents are completely reliant on UNRWA for their education, sanitation and healthcare needs. The amendments to UNRWA’s healthcare provisions follow changes to UNRWA’s education policy, fomenting a backlash against the agency from Palestinian refugees across Lebanon, including recent arrivals from Syria.

“[UNRWA is] abusing us to make us forget about returning to Palestine,” Nawal al-Jamal, a coordinator at the Active Aging House nongovernmental organization in Bourj al-Barajneh, told IBT. “People are very afraid about this, so they are saying, ‘Bring us back to Palestine and we will leave you alone.’ People are expecting that in the next few years all services will be closed.”

In Bourj al-Barajneh, most of the roughly 28,000 refugees who live among the winding, muddy alleys share al-Hussein’s fears. The camp is less than 20 minutes away from downtown Beirut, where Range Rovers and high-fashion stores line the streets, but the only things that line the streets in the camp are the tangled and tied electricity wires that cover the settlement like an explosive canopy. Many argue that UNRWA’s recent policy changes foreshadow a larger plan to empty the settlements, effectively stripping Palestinians of their refugee status and denying them their right to return to Palestine.

“They want to finish the refugees' cases. They are pressuring us to immigrate to [European Union] countries and forget about Palestine,” Mohammad Dabdoub, a member of the Palestinian faction Fatah in charge of Bourj al-Barajneh told IBT. “It’s a political issue, not a humanitarian issue. They have finished the Palestinian cases in Jordan, Iraq and Syria. There is only Lebanon that they have to deal with.”

To counteract the rumors, UNRWA organized a meeting with the leaders of Palestinian factions to explain the new policy and answer questions. But the clarity UNRWA sought to bring has yet to reach the very people it is trying to help, Darkazally said.

“Unfortunately not everything that was explained [in the meeting] was brought to the people," she said. "It has destabilized the environment for UNRWA. It is a bit hostile, but we continue our outreach.”

The spread of conspiracy theories and fear of more reductions in the camps comes as no surprise to Darkazally.

“When you’ve been waiting for 67 years and there’s no light at the end of the tunnel for your plight, and now subplights are appearing, of course you’re going to fall into conspiracy theories and believe them,” she said.

Khalida al-Hussein, a coordinator at a Palestinian NGO that operates in four camps across Lebanon, is one of the majority who have taken the claims seriously. He was one of some 100 Palestinians who demonstrated in front of UNRWA’s Beirut office to protest what he considers unfair aid cuts and a bid to forgo Palestinians’ right of return. Similar protests took place across Lebanon, organized by each camp’s popular committee. A large-scale demonstration involving all the camps is planned for Friday outside UNRWA’s main office in Lebanon.

“UNRWA is not only about services provided but is also a symbol [of] the international community” al-Hussein said. “By canceling UNRWA, [the international community is] canceling the Palestinian refugee status.”

But UNRWA says it has no intention of shutting down until a better solution has been found for Palestinian refugees across the Middle East. The policy readjustment, the organization says, is not an aid reduction but a rearrangement of its limited budget. Lebanon’s Palestinian camps have $10 million allotted for healthcare service, which is as much as the healthcare budgets for the West Bank, Gaza, Syria and Jordan combined, Darkazally said. The healthcare and education budget comes out of the General Fund, a pool of donations from which allocations are made to each country depending on its needs.

Palestinian refugees who have moved from Syria to Lebanon fall under the Emergency Fund category. These refugees cannot register with the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the U.N. organization in charge of all Syrian refugees, but must rely solely on UNRWA for aid, with the majority moving into the existing Palestinian camps in Lebanon.

The influx of Palestinian refugees from Syria has further crowded the already densely packed camps and forced UNRWA to make some cutbacks. Last year, the organization stopped subsidizing stationery and books in schools and didn't open any new facilities, meaning each classroom has up to 50 students.

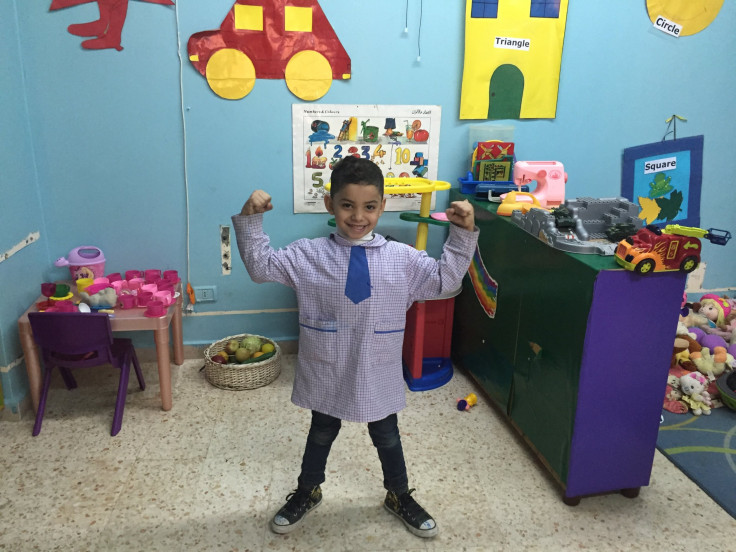

“Kids are hyper because their houses are very small; they can’t play. Sometimes it’s two families in one house,” Jimmy Jamal Jawad told IBT from her classroom in Bourj al-Barajneh, while her students jumped and screamed in excitement when lunch — manoushe, a kind of calzone stuffed with meat — arrived.

Jawad is a Palestinian refugee who, despite being born in Lebanon, has no legal status here. The 33-year-old has a law degree but couldn't find work after graduation. She married and moved to Bourj al-Barajneh, where she teaches English at a kindergarten school run by a Palestinian NGO.

Before lunch in class Friday morning, Jawad was teaching her students how to say where they are from in English.

“Where. Are. You. From,” she says slowly, asking 7-year-old Ahmad to answer.

“I am from Syria. You are from Syria?” he asks IBT with a huge grin. “I don't like Lebanon. It is very ugly.”

“No, you lived in Syria,” Jawad corrects him. “But you are from Palestine.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.