MH370 Search To Resume In Indian Ocean Six Months After Plane's Disappearance

The bottom of the South Indian Ocean is a deeply hostile environment, its landscape littered with jagged ridges and dramatic plunges that threaten to damage or swallow any unsuspecting visitor. It’s in this unsympathetic place that experts are looking for the remains of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370, which disappeared along with 239 passengers on March 8. After months of mapping the seabed’s treacherous contours -- a process that revealed two underwater volcanoes -- the team says it’s finally ready to resume its search.

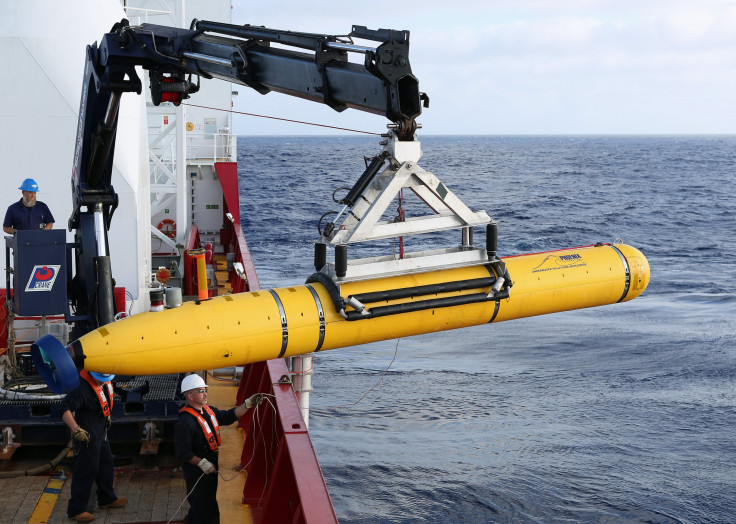

In two weeks, the Australian and Malaysian governments will deploy a fleet of exploration vessels to survey a 23,200 square mile strip of ocean named the “seventh arc,” where the aircraft is thought to have crashed. The vessels will pull sophisticated sonar devices called “towfish,” which look like tiny yellow submarines, and will be fitted with two types of sonar, highly-accurate GPS systems, multi-beam echo sounders and video cameras, Australia’s Joint Agency Coordination Center said late last month.

Australian and Malaysian officials said they would evenly split the cost of this new search phase, which could add up to $47.8 million and last up to a year. Dato’ Seri Liow, Malaysia’s transportation minister, said his country has already spent about $14 million to find the jet. The Australian government has set aside around $84 million for the search.

The nations suspended the mission’s first leg in May so that scientists could focus primarily on surveying the ocean floor. The South Indian Ocean is considered the least-mapped water in the world, and experts worried that blindly sending down critical and expensive search equipment would risk it getting damaged or lost.

So the Chinese survey ship Zhu Kezhen, the Australian-contracted ship Fugro Equator and a Royal Malaysian Navy vessel began trawling the waters, uncovering features like the volcanoes and the Broken Ridge, an area that begins at about 2,000 feet deep and suddenly drops to 22,000 feet deep. “It would not be safe to put the towed sonar equipment into the water if we didn't have this kind of vital information about the nature of the seabed,” Australia’s Deputy Prime Minister Warren Truss said at an Aug. 28 press conference with Malaysian and Chinese officials. “The mapping is absolutely essential to ensure the safety of the next stage of the search.”

Along with surveying the ocean, search teams analyzed new satellite data to refine their estimates on the Boeing 777 jetliner’s most likely location. That work helped shrink the possible search area down from an original span of 230,000 square miles.

In particular, a failed satellite telephone call from Malaysia Airlines operators on the ground to the aircraft offered clues to U.S. and British data experts. Although the plane’s precise coordinates couldn’t be pinned down, the plane’s system was still automatically connecting at regular intervals, giving operators so-called “handshakes” that proved it was still operating, The Economist reported. The seventh and final handshake came after seven hours and 38 minutes of flight. Investigators are convinced that this signal was in a response to the plane’s dwindling power supply.

“That has suggested to us that the aircraft may have turned south a little earlier than we had previously expected,” Truss explained. The search zone is still significantly off the plane’s original flight path from Kuala Lumpur to Beijing, with the newer estimates putting the plane’s possible location off the southern coast of India.

Truss said that the survey ships would continue mapping the seventh arc area, with the deep sea search vessels following behind them.

The Australian Transport Safety Bureau will lead the mission starting in mid-September. Australia will contract the Fugro Equator and its sister ship Fugro Discovery from a Netherlands-based surveying company. Malaysia will contract the vessel GO Phoenix, which will arrive first on the scene. The ships will drag the yellow towfish about 500 feet above the ocean floor using armored cables, through which data is transmitted back up to the surface. The Fugro vessels will also deploy hydrocarbon sensors based on the “sniffer” technology that oil companies use to detect leaks. They are sensitive enough to detect aviation fuel at trace amounts, The Economist noted.

“The high resolution search of the priority area on the sea floor is expected to take about 12 months to complete,” Truss said. “Together, the vessels will search this area in a systematic way so that we can be sure that the area is thoroughly covered.”

He added that, “All of the countries involved remain cautiously optimistic that we will find the missing aircraft."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.