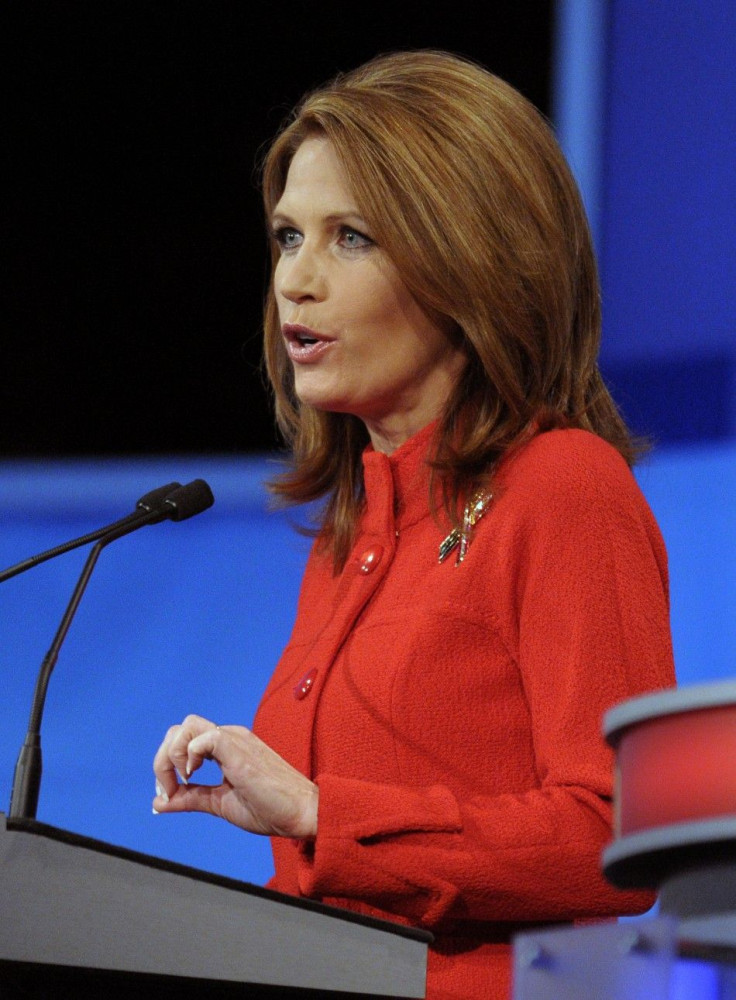

Michele Bachmann and Oral Roberts: What is a Christian Law School?

Michele Bachmann's evangelical Christian background once again came under scrutiny in a New York Times piece that detailed the Republican presidential hopeful's time at Oral Roberts University, a school of law that embeds its teachings in a Christian framework.

The piece probes how Bachmann absorbed biblically influenced legal doctrines such as the concept that God is the source of the law or the rejection fo any firm separation between church and state, beliefs that continue to inform Bachmann's politics.

They're teaching children that there is a separation of church and state, and I'm here to tell you that that's a myth -- that's not true, the article quotes Bachmann telling a Christian audience during her 2006 congressional campaign. The only reason we've been a great nation -- guess why? Because at our founding we established everything we did on the lordship of Christ.

While a conception of the law as being rooted in Christian teachings may fall outside the political mainstream, it is a guiding principle at Christian law schools throughout the country. Naomi Riley examined the phenomenon in her book God on the Quad: How Religious Colleges and the Missionary Generation Are Changing America. Riley stressed that she did not have any experience with Bob Roberts, but at Regent University -- which was founded by eminent evangelist Pat Robertson -- she characterized the curriculum as more of a broader philosophical context than substituting scirpture for jurisprudence.

On a fundamental level [the students] think the American system of law is compatible with and can be understood within a Christian moral view, Riley said. They have enormous respect for the founding documents as the supreme law of the land.

Riley added that many of the students she met were serious scholars who elected to attend Regent over secular schools because they wanted an unconventional education that reflected their moral beliefs.

What I found at most of these strongly Christian schools is the graduates need to be very competent at what they did, Riley added. They could not be pretending to get a legal education while they went to a glorified Bible school.

Still, schools like Regent or Oral Roberts are not without controversy. The Times article noted that the American Bar Association initially refused to accredit Oral Roberts, which a former professor attributed to a charge of too much emphasis on the Christian aspect and not enough on the law. Amidst allegations that Department of Justice lawyers serving working for George W. Bush had been fired for their political beliefs, Slate detailed how 150 members of the Bush administration were graduates of Regent.

The article charged that part of Regent's mission is to reassert Christian political authority, a goal Robertson seemed to endorse when he spoke to PBS about the university's desire to challenge the culture in areas including the law and to return America to the Judeo-Christian values from which he believed it has diverged.

A similar sentiment is on display in a promotional video for Trinity law school, a Christian university that seeks to educate, motivate and mobilize, according to the school's website. A student says he wants to know what secular judges and lawyers think so he can be equipped to work for reform in the legal system. Other people appearing in the video speak of how Christinianity forms the basis of western law and warn how radical skepticism has eroded that foundation by insisting on the autonomy of man and the autonomy of human law.

Trinity teaches the law as it was intended to be, one man says. As God intended it to be: handed down from his mind and taught to mankind.

You can contact the reporter at j.white@ibtimes.com

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.