Moon Is Being Hit By Meteorites More Frequently Than Previously Estimated

Many scientists and astronomers believe that before we get to Mars, we must colonize the moon. After all, with its low gravity and its virtually non-existent atmosphere, the moon can prove to be a good testing ground for technologies that may eventually be used in establishing Martian colonies.

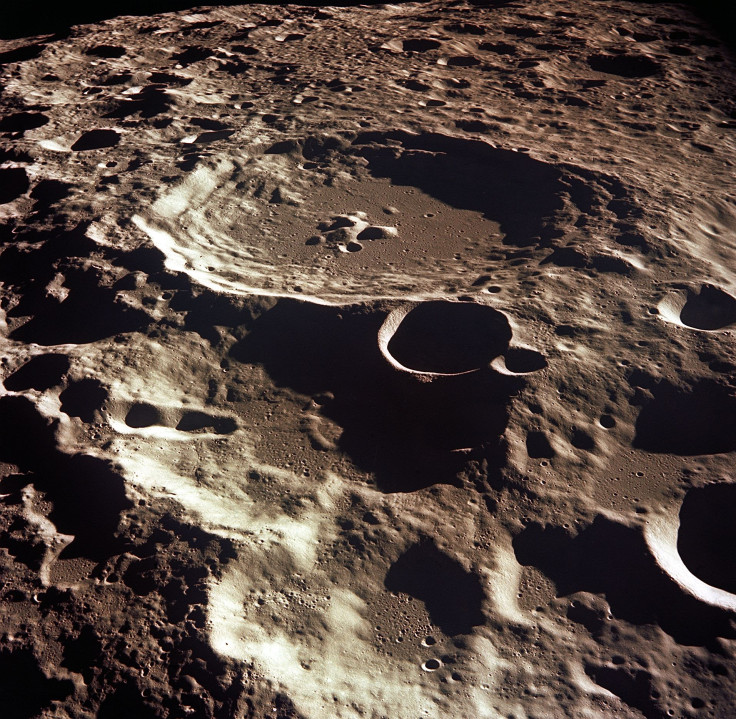

However, a new study based on an analysis of over 14,000 before-and-after images of the lunar surface has revealed something that may put paid to humankind’s hope to colonize the moon. The moon is being pummeled by meteorites far more frequently than previously assumed, and, as a result, the lunar surface is being “churned” over 100 times faster than earlier estimates suggested.

According to the authors of the study, who pored over years of high-resolution images captured by NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), meteorites have created at least 222 new craters in the past seven years alone — 33 percent more than researchers expected.

“It’s just something that's happening all the time,” lead author Emerson Speyerer, an engineer at Arizona State University in Tempe, told Nature.

The craters were found to be distributed randomly across the lunar surface, and ranged between 6 and 140 feet in diameter. Moreover, there were more fresh craters at least 33 feet in diameter than the current impact modeling rate calculations deem possible.

Each time a crater impacts the moon, it churns up the regolith, dislodging material that is then splattered across the lunar surface around the primary impact crater.

“Before the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter was launched in 2009, we thought that it took hundreds of thousands to millions of years to change the lunar surface layer significantly," Speyerer said in a statement. “But we've discovered that the moon's uppermost surface materials are completely turned over in something like 80,000 years.”

For future lunar habitats, this significantly increases the risk, as they would need to be protected against not just a direct meteorite impact, but also material splattered by such an impact.

A possible solution? Building the habitation modules of the lunar bases underground, where they would be protected from meteorite impacts.

However, even if future lunar colonies are below the lunar surface, several supply structures, rockets, rovers, and other equipment would still remain exposed and vulnerable to bombardment from space rocks and debris.

“For example, we found an 18-meter (59-foot) impact crater that formed on March 17, 2013, and it produced over 250 secondary impacts, some of which were at least 30 kilometers (18.6 miles) away,” Speyerer told Space.com. “Future lunar bases and surface assets will have to be designed to withstand up to 500 meter per second (1,120 mph) impacts of small particles.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.