NASA Captures Stunning 'Cosmic Jellyfish' With Blue 'Tentacles' In Detailed View [PHOTOS]

NASA previously captured a stunning cosmic "jellyfish" with blue "tentacles" millions of light-years away from Earth.

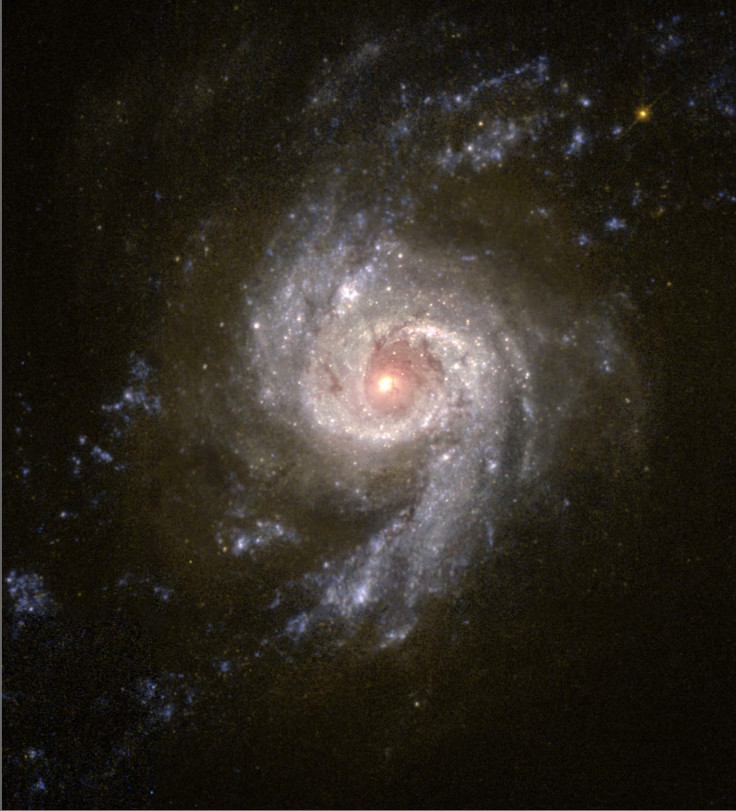

On the official Twitter page of NASA's James Webb Space Telescope, the U.S. space agency shared two incredibly detailed images of galaxy ESO 137-001. In the image taken by the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope, the spiral galaxy appears to have a "jellyfish" shape due to the blue "tentacles of young stars dangling from its disk."

However, the second photo, a composite image created by combining X-ray data from Chandra X-Ray Observatory with the Hubble's visible light, showed a "giant tail of hot gas streams behind the galaxy."

In visible light, this galaxy looks like a jellyfish with blue "tentacles" of young stars dangling from its disk. In X-ray light, a giant tail of hot gas streams behind the galaxy. Infrared #NASAWebb will study this tail of gas & the stars forming in it. https://t.co/4J2YGWYE2l pic.twitter.com/pWKd4rNOXD

— NASA Webb Telescope (@NASAWebb) April 17, 2019

The "jellyfish galaxy" is part of a cluster called Abell 3627 and is around the same size as the Milky Way Galaxy, though slightly less massive. Its tail is about three times its diameter, reaching up to 260,000 light-years in length.

As for why NASA put the "jellyfish" galaxy back in the spotlight, ESO 137-001 will soon be observed and studied by the James Webb Space Telescope when it is launched in 2021, according to a statement on NASA's website.

Astronomers have been fascinated by the newly forming stars in galaxy ESO 137-001's tail which should not have been born due to the "ram pressure stripping." This happens when the gas surrounding galaxies acts as a headwind and blows away dust and gas required for star formation.

However, in galaxy ESO 137-001's case, stars appear to be forming in its massive tail, and these will be studied by the upcoming Webb telescope. Specifically, it will focus on three different sites of star formation: close to the galaxy, in the middle and near the end of the tail.

Researchers will try to figure out how stars are being born in the tail when the stripping process should have made this impossible.

“We think it’s hard to strip off a molecular cloud that’s already forming stars because it should be tightly bound to the galaxy by gravity. Which means either we’re wrong, or this gas got stripped off and heated up, but then had to cool again so that it could condense and form stars,” Stacey Alberts of the University of Arizona, a co-investigator on the project, said in a statement.

“Telling these two scenarios apart is one of the things we want to get at,” she added.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.