NASA's Hubble Telescope To Search For Exomoon Kepler 1625b-i

In July, a team of researchers led by Alex Teachey and David Kipping of Columbia University suggested the existence of a moon called Kepler 1625 b-i circling a planet outside of our solar system. They provided evidence that points towards its presence. Though it is not sure if it exists or not, the proof offered by Teachey and Kipling set-off speculation of what the exomoon could be like. To prove or disprove their claims, the Hubble Space Telescope will try and locate it this weekend.

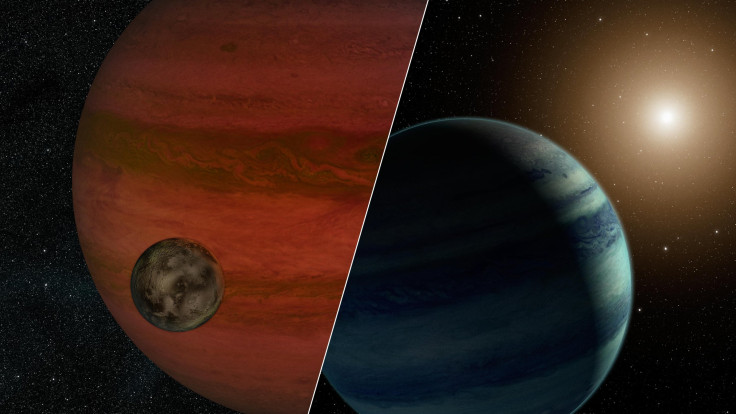

A recent paper published by René Heller, a space scientist with the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, has tried to offer a preview of what the exomoon would look like if it exists. In his paper, Heller describes the research he has conducted studying the Kepler data that suggests the possible exomoon.

He says that the data is not decisive enough to accurately judge the size of the moon. In his Aug. 11 paper published in ArXiv, he suggests that calculations point to a moon that could be anywhere from approximately the size of the Earth to the size of Saturn. According to a Phys.Org report, He does not suggest the data proves the existence of an exomoon, but does say that it would approximately be the size of Neptune.

As per his statements, a moon the size of Neptune does not exist in our own solar system. This shows that, if exomoons that large do exist elsewhere, our existing theories for moon formation suggest it likely formed in ways that are not described by one of the three main moon creation theories.

Our existing theories hold that moons were formed because of a huge impact on a planet, assimilation of material orbiting a planet, or a passing object captured by a planet's gravity. According to the Phys.Org report, "this means that if the exomoon is confirmed and its size and makeup can be determined, it is likely that there will be a race between space groups around the world to find a theory explaining its existence."

The predictions have led to a flurry of activity in the search for exomoons. The Hubble Space Telescope would look to locate and study the Kepler 1625 b-i exomoon. The data could either prove or disprove the claims made by Teachey and Kipping. The whole space community is poised to study the first exomoon, provided it exists. The find could see us reconfigure existing moon formation theories, making the weekend search all the more important.

According to the Phys.Org report, "Teachey and Kipping have been vocal about their view that researchers should wait to see if the exomoon exists before conducting research or creating theories, lest it all be in vain." They are waiting for the weekend when the Hubble Space Telescope will be aimed at the system, possibly confirming or ruling out its existence. This could change theories and also give us an understanding of the different ways other planetary systems developed.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.