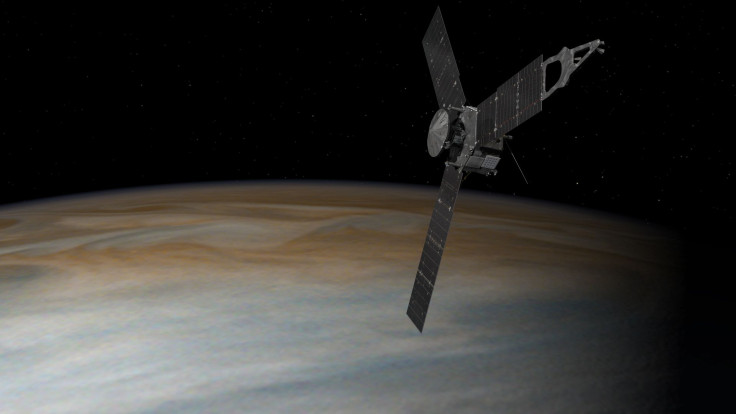

NASA’s Juno Mission: Spacecraft ‘Healthy’ After Unexpectedly Entering Safe Mode Hours Before Jupiter Flyby

NASA’s Juno spacecraft unexpectedly entered a safe mode early Wednesday, just hours before its eagerly awaited a second close flyby of Jupiter. This means that all its science instruments were turned off, and that the planned data collection during the flyby did not take place.

However, in a statement released Thursday, the space agency clarified that the spacecraft behaved as expected during its transition into safe mode, and had since rebooted successfully.

Safe and sound. I went into safe mode for today's close flyby of #Jupiter, but I’m just fine. Mission status: https://t.co/3FYBIHoCc8 pic.twitter.com/NedfwgBAxM

— NASA's Juno Mission (@NASAJuno) October 19, 2016

“At the time safe mode was entered, the spacecraft was more than 13 hours from its closest approach to Jupiter,” Rick Nybakken, Juno project manager from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, said in the statement. “We were still quite a ways from the planet’s more intense radiation belts and magnetic fields. The spacecraft is healthy and we are working our standard recovery procedure.”

It is still not clear what caused Juno to go into safe mode. It is designed to do so only when the onboard computer perceives that certain conditions are not as expected.

Wednesday’s incident occurred just days after NASA was forced to postpone a maneuver that would have shortened the spacecraft’s orbital period from its current 53 days to 14 days. The decision was made after scientists at NASA discovered that a pair of check valves that regulate the flow of helium to Juno’s engines was malfunctioning.

“The valves should have opened in a few seconds, but it took several minutes. We need to better understand this issue before moving forward with a burn of the main engine,” Nybakken said in a statement released Friday.

The next close flyby is scheduled for Dec. 11, when NASA hopes to have all of Juno’s science instruments switched on. Until then, scientists at the space agency will continue analyzing data collected during the first perijove pass on Aug. 27.

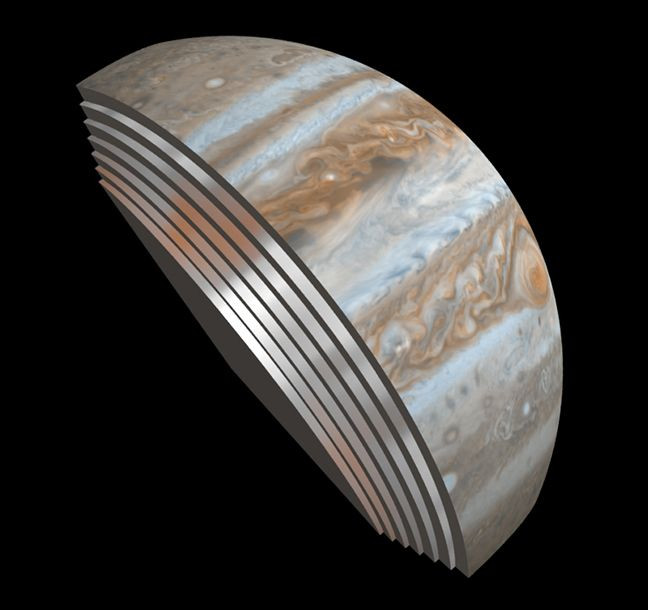

“Revelations from that flyby include that Jupiter’s magnetic fields and aurora are bigger and more powerful than originally thought,” NASA said in the statement. “Juno’s Microwave Radiometer instrument (MWR) also provided data that give mission scientists their first glimpse below the planet’s swirling cloud deck. The radiometer instrument can peer about 215 to 250 miles (350 to 400 kilometers) below Jupiter’s clouds.”

Juno was launched in August 2011 and traversed nearly 2 billion miles of space to reach the largest planet in our solar system. The primary goals of the $1.1 billion mission are to find out whether Jupiter has a solid core, and whether there is water in the planet's atmosphere — something that may not only provide vital clues to how the planet formed and evolved, but also to how the solar system we live in came into existence.

At the end of its mission, Juno will dive into Jupiter’s atmosphere and burn up — a "deorbit" maneuver that is necessary to ensure that it does not crash into and contaminate the Jovian moons Europa, Ganymede and Callisto.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.