Obama Administration Proposes Offshore Oil And Gas Drilling Along East Coast

The Obama administration is proposing to allow offshore oil and gas drilling in a slice of federal waters from Virginia to Georgia. Energy companies, which have long urged officials to expand America's offshore production, are hailing the move, but the proposal is drawing criticism from environmental groups worried about the dangers of ocean oil spills and climate change.

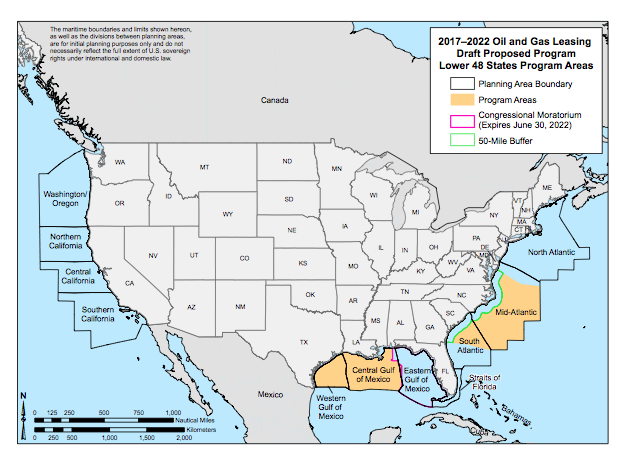

The U.S. Interior Department's five-year proposal for the period 2017 to 2022 would auction off one offshore drilling lease in the combined Mid-Atlantic and South Atlantic zones. The federal government hasn't issued a new lease in this area for more than 30 years due to regulatory and economic concerns.

"At this early stage in considering a lease sale in the Atlantic, we are looking to build up our understanding of resource potential, as well as risks to the environment and other uses," Interior Secretary Sally Jewell said in a statement Tuesday.

The department said it wouldn't auction off the Atlantic leases for at least six years, and drilling isn't likely to start until several years after that. The plan also proposes to offer 10 lease sales in the Gulf of Mexico and one sale each for three assigned areas in offshore Alaska.

If the initial Atlantic project is successful, it could unleash billions of barrels of untapped oil and gas reserves and further fuel America's energy boom.

The Interior's Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), which will run the auction, estimates the Atlantic's outer continental shelf holds 3.3 billion barrels of recoverable crude oil and 31.3 trillion cubic feet in natural gas reserves -- around 1.5 percent each of the total recoverable U.S. oil and gas reserves, both offshore and onshore, according to federal energy data.

But energy industry experts say the outer shelf may actually contain far more oil and gas than estimated. The BOEM numbers are based on 1980s surveys conducted with outdated seismic technology. "The data is old and incomplete ... and needs to be taken with a grain of salt," says Fred Beach, assistant director of energy policy at the University of Texas' Energy Institute in Austin.

The announcement comes as plunging crude oil prices are forcing companies to postpone or shelve high-cost offshore developments. Transocean Ltd., a Swiss firm that rents floating mobile drill rigs, took a $2.6 billion "impairment charge" in the third quarter of 2014, citing a "decline in the market valuation of the company's contract drilling services business." Schlumberger Ltd., a top global offshore and onshore services provider, said it slashed 9,000 jobs late last year, or 7.5 percent of its global workforce, after its fourth-quarter profit plunged by more than 80 percent.

Industry observers say that shouldn't dampen interest in the Atlantic's outer continental shelf. "Even in a time of sinking oil prices, exploration companies are planning for the long term," says Nicolette Nye, a spokeswoman for the National Ocean Industries Association, a trade group that supports offshore drilling. "We don't really know what the price of oil will be when the plan goes into effect."

Brent crude, an international benchmark, was trading at $48.33 a barrel Tuesday afternoon, while U.S. West Texas Intermediate was trading for $45.29 a barrel. Both benchmarks are down by more than 50 percent compared with last summer due to an enduring global supply glut.

Beach speculated that oil prices eventually would balance out around $70 to $80 a barrel -- a price that he said would justify drilling in the Atlantic shelf. "At those kinds of prices, offshore oil is very affordable," he says. "In some cases, it may be even more affordable than onshore tight oil," which is also called shale oil.

He noted that shale drilling requires expensive hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, to crack open geological formations and unleash oil and gas reserves. The continental shelf, by contrast, has conventional oil resources. "You poke a hole in the ground and it comes gushing out ... or you have to pump it out," Beach says. That ease of extraction could offset the higher costs associated with drilling out on the water, he added.

Atlantic oil and gas reserves are also accessible at shallower depths than the deposits in the Gulf of Mexico or offshore Alaska, Beach noted, making them cheaper to exploit. The deepest Atlantic reserves are about 1,000 feet below the surface, about one-fourth the depth of "deepwater" rigs, including BP's Deepwater Horizon operation that exploded in 2010, dumping more than 3 million barrels of oil in the Gulf of Mexico and killing 11 rig workers.

Environmentalists have pointed to the oil spill catastrophe in expressing their opposition to the Atlantic drilling proposal. The Obama administration's decision "takes us in exactly the wrong direction ... and ignores the lessons of the disastrous BP blowout," Peter Lehner, executive director of the Natural Resources Defense Council, said in a statement. "It would expose the Eastern seaboard, much of the Atlantic and most of the Arctic to the hazards of offshore drilling."

The Atlantic region hasn't seen offshore oil and gas drilling in more than 30 years, according to the Interior Department. Fifty-one wells were drilled there from 1975 to 1984, including five tests wells and 46 industry wells.

The government held its last oil and gas lease sale in 1983. In early 2010, the Obama administration had proposed a five-year plan to allow for new lease sales in federal waters off Virginia, but officials dropped the idea in the aftermath of the BP spill.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.