Observations Of Ancient Galaxies Reveal Massive Halos Of Hydrogen Gas

A long, long time ago, when the universe was still young, it was populated with galaxies that were quite unlike what we see around us today. Understanding what galaxies like the Milky Way looked like in the formative years of the universe — about a billion years after the Big Bang — has been a key goal of astronomers seeking to get a clearer picture of how galaxies form and evolve.

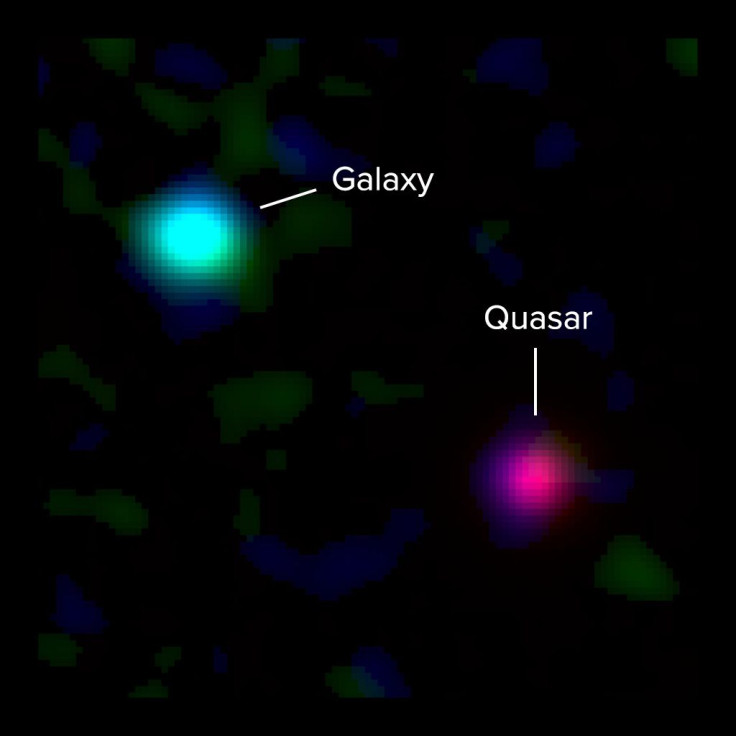

In a study published Friday in the journal Science, a team of astronomers has described observations of two distant galaxies made using the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile. The observations, coupled with previous ones made by analyzing their quasar absorption signatures, reveal that these galaxies are embedded in massive halos of hydrogen gas.

“We had expected we would see faint emissions right on top of the quasar, and instead we saw bright galaxies at large separations from the quasar,” study co-author J. Xavier Prochaska, a professor of astronomy and astrophysics at the University of California, Santa Cruz, said in a statement.

It has long been standard practice to use quasars, which are bright cores of distant active galaxies, to detect distant objects. As the light from background quasars passes through the gas and dust in foreground galaxies, it carries with it information about the speed, composition and temperature of the galaxies.

For this particular study, the researchers used ALMA telescopes to directly image the gas in the young galaxies — both of which were seen as they were 12 billion years ago — and were able to actually see the millimeter-wavelength glow emitted by ionized gas in the dense star-forming regions.

“We've been wanting to do this for 14 years,” Prochaska said. "The 'holy grail' has been to identify and study the galaxies that host the hydrogen gas we see in quasar spectra, and it took a facility with ALMA's capability to do it.”

When the researchers compared the ALMA observations with the measurements made using background quasars, they found a curious discrepancy — the glow of ionized gas in the star-forming regions are considerably offset from the gas detected by quasar observations. This means that each galaxy is embedded in a gigantic halo of hydrogen gas.

“It's not where the star formation is, and to see so much gas that far from the star-forming region means there is a large amount of neutral hydrogen around the galaxy,” study lead author Marcel Neeleman, also from the University of California, said in the statement.

Astronomers are still not sure why the halos are much larger than previously believed possible, and whether these are just extended disks of gas falling into the galaxies. Further observations using ALMA telescopes are likely to refine their understanding of what galaxies in the universe’s adolescence looked like.

“We can now see the galaxies themselves, which gives us an amazing opportunity to learn about the earliest history of our own galaxy and others like it,” Neeleman said in a separate statement.

Milky Way-Like Galaxies in the Early Universe from NRAO Outreach on Vimeo.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.