Panama Canal Expansion Could Mean Tougher Times For Egypt's Suez, As Revenues Lag Despite Sisi's Promises

Not everyone is thrilled with the new and improved Panama Canal. The expansion of the storied channel was unveiled to great fanfare Sunday, but for one country in particular, it contains more threat than promise.

Egypt embarked in 2014 on a yearlong expansion of its own historic Suez Canal, a project that officials dubbed “The Great Egyptian Dream.” President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi officially inaugurated the new Suez Canal in August, but it has since failed to live up to the promises of drawing more ships, boosting revenues and creating jobs that authorities promised.

Now, the revamped Panama Canal gives Egypt even greater cause for concern. Although each route has its key markets (for Suez, it’s Asia and Europe, for Panama it’s South America) cargo shipped from Northeast Asia to the East Coast of the U.S. often flows through one of these two portals.

Panama’s expansion would “persuad[e] new players to consider the Panama Canal route” and “recover market” from the Suez Canal, according to a presentation that Oscar Bazán, executive vice president of planning and business development for the Panama Canal Authority, gave at the Georgia Foreign Trade Conference, in Sea Island, Georgia in February.

Panama spent more than eight years and $5 billion doubling the capacity of the 102-year-old channel between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. It created a new lane allowing vessels with a capacity nearly triple that of ships that the channel could previously accommodate.

By facilitating the passage of fewer but larger ships carrying more goods, Panama’s expansion is projected to cut global shipping costs by some $8 billion annually. Authorities also estimated that ships traveling between Asia and the U.S. East and Gulf coasts would shave anywhere from eight to 16 days off their journeys, thanks to a bigger waterway.

In the years before the expansion, Panama was losing share to Suez, which saw its share of shipping traffic from Asia to the East Coast rise from roughly 30 percent in 2009 to 42 percent by late 2013. With the shipping industry shifting toward the use of more efficient megaships, the larger, deeper Suez Canal’s ability to accommodate these enormous vessels gave it an advantage over Panama. By 2015, the Suez Canal’s weekly capacity was nearly double that of the Panama Canal, capturing about about 65 percent of Asia-to-North America trade, according to the trade publication American Shipper.

Will this picture change with the expanded Panama Canal? pic.twitter.com/2cdEaghXAv

— Elizabeth Whitman (@elizabethwhitty) June 27, 2016

Some have suggested that Egypt’s rapid expansion of the Suez Canal was prompted by a need to pre-emptively protect Egypt’s market share in global shipping from the clutches of Panama.

The Suez Canal is now 95 kilometers, or 59 miles, long, compared to its original 60 kilometers (37.2 miles). The $8 billion project also added to, widened or deepened various shipping bypasses to allow for two-way traffic in some parts and for larger ships in others. By expanding the canal, Egypt hoped to reduce transit times for southbound vessels to 11 hours from 18, as well as to minimize ships’ wait times.

Ultimately, the aim was to “attract more ships to use the Suez Canal” and improve the its standing as “an important international maritime route,” according to the official Suez Canal website. The expansion is predicted to raise canal revenues from $5.3 billion in 2014 to more than $13.2 billion by 2023, create jobs for Egyptian youth and “maximize competitiveness of the Suez Canal,” officials promised, although independent observers have greeted these calculations with healthy skepticism.

Underlying these claims was a sense of competition between Suez and Panama that, at times, played out comically:

#Egypt issues stamps to celebrate new addition to Suez. "Borrow" Panama canal pics to illustrate. #FAIL H/T @_amroali pic.twitter.com/zErsOXqJ4A

— Sheera Frenkel (@sheeraf) September 13, 2014

Despite the expansion, revenues for the Suez Canal dropped in 2015 to $5.175 billion from $5.465 billion the previous year. One factor was an overall global decline in shipping. Another is the strength of the U.S. dollar, which can lower revenues given that the Suez Canal’s transit tolls are calculated using a combination of several currencies, including the euro, U.S. dollar and British pound. A global slump in fuel prices, meanwhile, meant that for some ships, it was actually less expensive to sail around South Africa than to pay transit fees for the Suez Canal.

Egypt deployed number of tactics to draw traffic back to the Suez Canal, but the Panama upgrade could jeopardize those efforts.

Starting March 7, the Suez Canal Authority cut tolls by 30 percent for certain ships, the Journal of Commerce reported. The discount lasted until June 5, although the authority has the ability to renew it. It applied to ships sailing from the Port of New York and New Jersey to destinations in Southeast Asia.

In February, Egypt also opened a new shipping channel connecting the East Port Said Harbor with the Mediterranean Sea. It was supposed to alleviate congestion at the entrance to the Suez, where ships that wanted to enter the harbor previously had to wait, in order to use one of its channels.

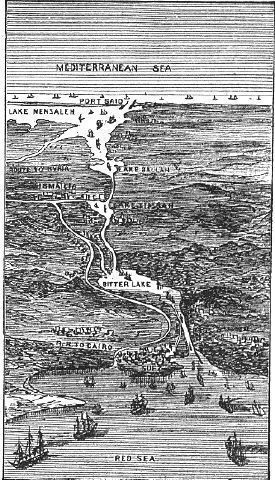

The Suez Canal opened Nov. 17, 1869, although efforts to connect the Mediterranean Sea with the Red Sea date as far back as the age of Pharoah Senwosret III, who ruled from roughly 1878 to 1840 B.C. The canal in its modern iteration represented the first water route between those two bodies of water, but as numerous economists and experts have pointed out, the 21st-century update of the Suez Canal doesn’t represent nearly as momentous a change — especially when it has the Panama Canal as its rival.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.