Pandemic Increases Isolation Of Argentina's Desert Children

Argentina's coronavirus lockdown has closed schools nationwide and driven teaching online, but nowhere are the wasted weeks felt more keenly than in Huarpe indigenous communities in the far north, which have little access to the internet or distance education.

Around a thousand Huarpe families live in 11 communities scattered across the arid wasteland of northern Mendoza province.

Distance learning is out of reach for these desert communities, who live in simple dwellings and mostly subsist on raising goats.

"We are very far from the systems of communication, and this makes it impossible for my children and the children of neighbors to have access to the internet, and the communications that you in the city have around every corner," said Jorge Lecinas, 40.

Many Huarpe families send their children away to school for several weeks a month. Others attend rural schools where they also get lunch.

But when the rural schools shut as the country went into mandatory quarantine on March 20, so did the meals from the ministry of education, drying up a vital means of nutrition for deprived children.

Argentina's recession means 35 percent of the 44 million population is living below the poverty line, according to official statistics, and one in every three children is poor.

Among the Huarpes, all children are poor.

Gonzalo Lencinas solemnly sits in his chair to do his homework on a rickety wood table in the dirt yard of his half-built home.

Around him the desert stretches to the horizon. His home is the only construction for miles.

The 10-year-old says he misses his school, his teachers and playing football with his friends in the school playground.

Teachers providing outreach are the Huarpes only link with the education system now.

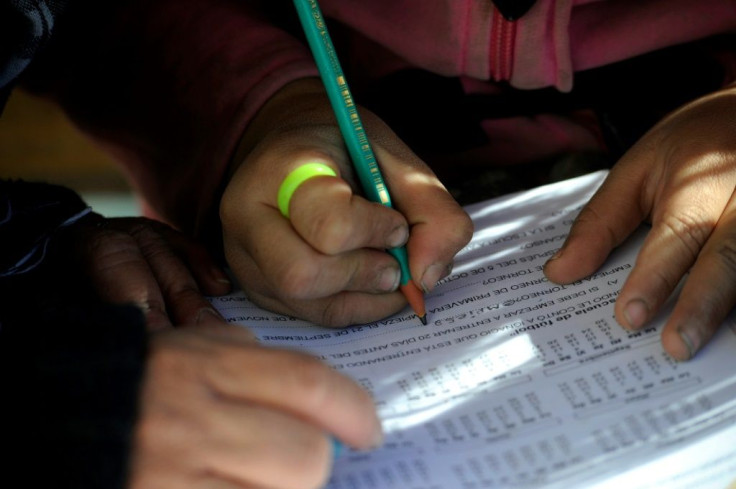

They travel distances of about 400 kilometers (250 miles) weekly or fortnightly to bring them books and homework, along with food bags.

The meeting point is often a dusty roadside in the middle of nowhere.

Raquel Cabrera has seven children. Her eldest, Martin, is 16 and spends hours on the roof of the family home hoping to capture a signal on his mobile phone, a common frustration for teenagers here.

The internet signal is almost non-existent, like the rain that barely, if ever, moistens the desert landscape, more than 1100 kilometers (700 miles) west of Buenos Aires.

"We help them as much as we can," said Cabrera of her children.

"There are homework tasks that the boys don't understand and since they do not have the internet they cannot do them.

"I don't understand them either," she said.

The education ministry decided to scrap school grades during the pandemic. But experts have warned that unequal access to the internet is causing a growing education gap nonetheless.

Marta Perez, the teacher in the nearest school, says the shortcomings of the Huarpes go beyond connectivity.

"They don't even have the possibility of looking up the meaning of some words because they don't have dictionaries," she said.

"They lack a lot of things economically, water is scarce and what water they have has arsenic!" she said.

The pandemic's restrictions have brought unexpected problems for the community of El Retamo.

The only bus service comes once a week. But under the lockdown, people in Mendoza province can only leave their homes on specific days according to their ID number, which is difficult to reconcile with the irregular transport link.

Mendoza has just 88 of the more than 6,800 coronavirus infections nationally, and 10 of the 329 deaths.

Social distancing, the only known preventive weapon against the coronavirus, comes naturally.

Visiting a neighbor here means travelling several kilometers along dirt roads to the nearest house.

"The Huarpes communities have also been affected by this situation which is hitting us at a global level," said Dario Jufre, as he collected homework for his children.

It has driven home to them how very isolated they are.

"It's been a very difficult situation because it has made us see that we are way outside the communications systems."

© Copyright AFP {{Year}}. All rights reserved.