Part Human, Part Neanderthal Skulls Found In China Trigger Debate: Did They Belong To The Mysterious Denisovans?

The evolutionary history of modern humans (Homo sapiens) is a messy one. After they first ventured out of Africa roughly 60,000 years ago, our ancestors not only displaced the indigenous populations of Neanderthals in Europe in West Asia, they also mated extensively with them — an activity that has left behind its footprints in our genome.

The hominid fossil record from East Asia, however, is patchier, making the reconstruction of our evolutionary history and population patterns in the region an extremely daunting task.

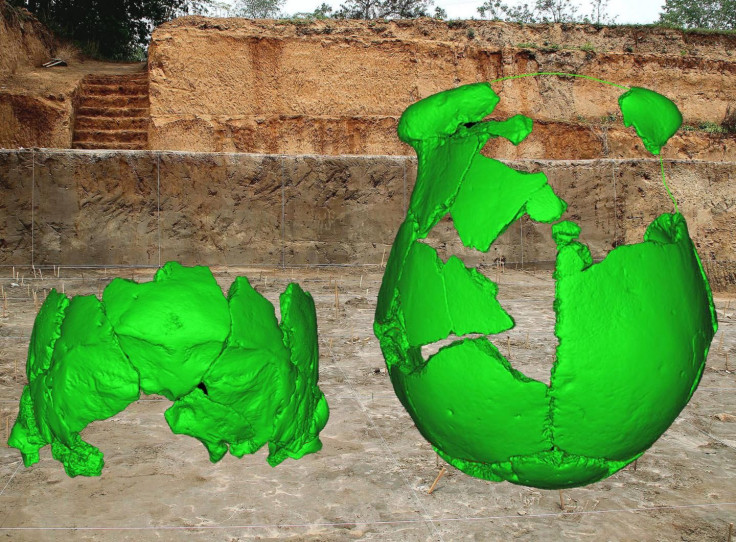

It is in this backdrop that the discovery of two partial skulls in the China, described in a new study published in the journal Science, assumes special importance. What makes the skulls — discovered between 2007 and 2014 in Lingjing, Xuchang County in Henan Province — even more intriguing is the curious “mosaic” of features they exhibit.

The skulls, estimated to be about 100,000 years old, display traits that have never before been seen in our fossil record — features that are neither pure Neanderthal nor pure human (or any other known hominid species, for that matter).

“Some features are ancestral and similar to those of earlier eastern Eurasian humans, some are derived and shared with contemporaneous or later humans elsewhere, and some are closer to those of Neandertals,” the researchers wrote in the study.

For instance, the cranial remains show that much like early modern humans, the individuals that possessed them had a large brain volume (roughly 1,800 cubic centimetres, which is the upper end for both modern humans and Neanderthals). However, features that were quite pronounced in earlier humans, such as the bony ridges over the eyes and a bony prominence at the back of the skull, are not prominent in these skulls.

Furthermore, the specimen show a configuration of semicircular ear canals and an enlarged section at the rear — structures that have previously been found in Neanderthal skulls.

“The features of these fossils reinforce a pattern of regional population continuity in eastern Eurasia, combined with shared long-terms trends in human biology and populational connections across Eurasia,” study co-author Erik Trinkaus, a professor of anthropology at Washington University in St. Louis, said in a statement. “They reinforce the unity and dynamic nature of human evolution leading up to modern human emergence.”

Many have already begun speculating that the skulls may have belonged to Denisovans — a mysterious group of humans whose existence has only been gleaned from the DNA analysis of a few finger bones and teeth found in a cave in Siberia.

“Unfortunately, the skulls lack teeth so we cannot make direct comparisons with the large teeth known from Denisova Cave, but another similarly-dated fossil from Xujiayao in China does have Neanderthal-like traits in the ear bones, like Xuchang, and does have large teeth, so these may all represent the same population,” Chris Stringer, a professor at London’s Natural History Museum, who was not involved in the study, told BBC News. “We must hope that ancient DNA can be recovered from these fossils in order to test whether they are Denisovans, or a distinct lineage.”

For now, the only thing we know for sure is that the skulls belonged to an “archaic Homo” species that lived in East Asia about 100,000 years ago.

“The biological nature of the immediate predecessors of modern humans in eastern Eurasia has been poorly known from the human fossil record,” Trinkaus said in the statement. “The discovery of these skulls of late archaic humans, from Xuchang, substantially increases our knowledge of these people.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.