Perfect Swarms: Cicadas Aren't The Only Bugs That Have Plagued America

People from Pennsylvania to Maryland are on tenterhooks, waiting for the telltale buzz to start: Cicada season is almost upon the U.S. East Coast. Anywhere from 30 billion to 1 trillion cicadas are expected to crawl out of the ground in the coming weeks. If Brood II, the group of 17-year cicadas that’s just waking up from a long dirt nap, really does turn out to be 1 trillion strong, it could be one of the biggest insect swarms in U.S. history.

Although the cicada’s 100-decibel mating call can be kind of annoying, these bugs neither sting nor devour everything within range. Other swarming insects aren’t quite so benign.

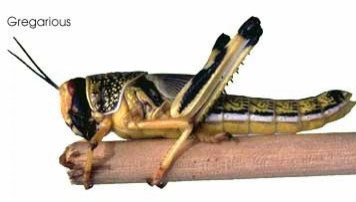

When you think of insect swarms, your first thought -- thanks to the Book of Exodus -- is probably of locusts. The locust isn’t actually a separate species of insect: The term is applied to any one of several species that can make the switch into swarming behavior if they get too crowded. Usually this lifestyle change is accompanied by a color change, typically to a bright yellow.

Masses of locusts are ravenous eating machines, and can wreak havoc on crops. Here are some of the biggest gatherings of locusts ever recorded:

Locust swarms, U.S. Great Plains, 1873-1877: In the classic “On the Banks of Plum Creek,” author Laura Ingalls Wilder wrote about a massive cloud of grasshoppers that devoured her family’s wheat crops: “The cloud was hailing grasshoppers. The cloud was grasshoppers. Their bodies hid the sun and made darkness ... Laura tried to beat them off. Their claws clung to her skin and her dress ... Grasshoppers covered the ground, there was not one bare bit to step on. Laura had to step on grasshoppers and they smashed squirming and slimy under her feet.”

Wilder based that account on actual encounters her family had in Minnesota with the Rocky Mountain locust, a now-extinct species that afflicted the prairies of the U.S. and Canada in the 19th century. Little did anyone know that swarms like the ones in the 1870s that plagued the Ingalls family would be the last major flight of the Rocky Mountain locust.

In 1875, A.L. Child of the U.S. Signal Corps observed an intense swarm streaming overhead at his post in Plattsmouth, Neb. He calculated the insects’ speed and alerted towns that lay in the locusts’ path about the approaching swarm. Child estimated that the swarm was about 1,800 miles long and 110 miles wide -- almost large enough to blanket both Wyoming and Colorado combined, according to High Country News.

Locust swarm, Kenya, 1954: Air reconnaissance photos captured some of the first reliable records of locust swarms. In a particularly harsh season that year, 50 locust swarms blanketed more than 1,000 square kilometers (386 square miles) with an estimated total of 50 billion locusts. The largest of the swarms covered 200 square kilometers (77 square miles) and contained about 10 billion locusts, according to the University of Florida’s Book of Insect Records.

While nowhere near as large as a locust swarm, a cloud of bees can be especially frightening if you start imagining all those stingers trained on you. In reality, honey-bee swarms have no incentive to attack -- after leaving the hive, they have no young or food stores to protect. They’re typically not dangerous unless severely provoked.

Bees typically swarm when they’re seeking new housing thanks to overcrowding, but will also swarm as part of their natural life cycle. Beekeepers attempt to reduce swarming as much as possible, but they can’t always control every queen and her subjects, Plus, there are wild honey bees to consider.

Bee swarm, New York, 2011: It didn’t swallow up thousands of miles of farmland, but one bee swarm with 15,000 insects did occupy some prime real estate a few years back: the corner of Grand and Mulberry Street streets in Manhattan’s Little Italy neighborhood. The bees blanketed one side of a mailbox, but were shortly corralled by beekeepers sanctioned by the New York Police Department, according to DNAinfo.

Multiple bee swarms, New York, 2012: Beekeeping is all the rage on the rooftops of Brooklyn and other boroughs, but that local honey comes with swarms that amateur apiarists might not be prepared to handle. Last June, the New York Post reported that within a single month, the NYPD and its crack team of bee wranglers had to remove tens of thousands of wayward bees from a tree in the Bowery; from a fire hydrant in Lower Manhattan; and from a family’s SUV.

On the West Coast, you might not get to experience many cicada swarms, but you can sometimes experience an even more beautiful swarm: the monarch butterfly migration that moves southward in August, and northward in spring.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.