Police State: New Uganda Law Threatens Public Gatherings, Further Squeezes Dissent

Police in Uganda are taking full advantage of a controversial new law meant to regulate public gatherings, but critics worry it spells bad news for political freedom in the East African country.

Called the Public Order Management Bill, the law passed in parliament on Aug. 6 and mandates that any public assemblies require police permission in advance. Citizens received a clue just how strictly officials plan to enforce it this week, when a police officer suggested that even small, in-home meetings might come under scrutiny.

"As the police, we must know about every meeting, even if it is in your home," Sam Omala, police operations commander for the capital city of Kampala, said in Ugandan newspaper The Observer.

That statement came after officials shut down a Tuesday morning conference organized by the Citizens Alliance, a coalition of opposition politicians and civil society groups who are opposed to bill. The police seized organizers' equipment and arrested at least 10 participants, with Omala demanding to know whether the Citizens Alliance had gained permission to gather beforehand.

Now, Ugandans are wondering how far the police will go and whether “family discussions“ are indeed subject to the new law. Human rights activists in Uganda and around the world are concerned that the bill will have far-reaching effects in a country that already has a reputation for stifling dissent.

"This bill is a devastating blow for freedom of expression and assembly in Uganda," Human Rights Watch Senior Africa Researcher Maria Burnett said in a statement. "With this law in force, any spontaneous peaceful demonstration of more than three people will be a criminal act."

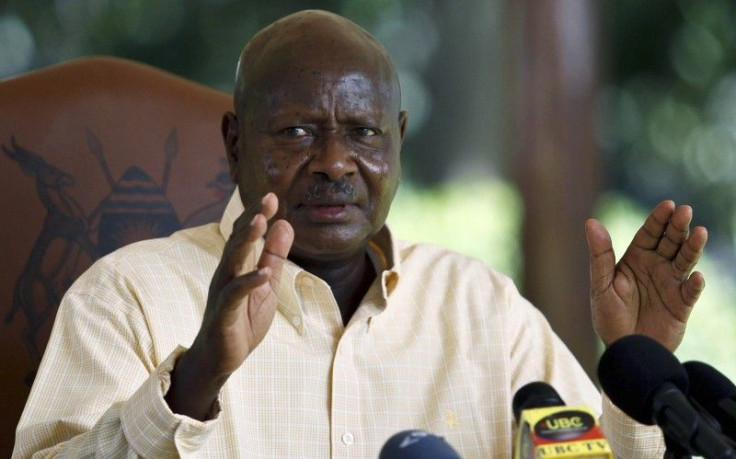

Uganda has come a long way since the 1970s, when it was plagued by violence and political upheaval. Yoweri Museveni became president in 1986, and under his watch the country has witnessed greater stability and fast economic growth. The World Bank predicts a GDP expansion of 6.5 percent for the fiscal year 2013/14, due in large part to successful policies for investment in various sectors including services, construction and energy. Oil discoveries over the past few years have encouraged foreign investment, and the country is expected to begin producing crude in 2018.

Museveni's critics argue that when it comes to human rights and democratic freedom, progress has been far too slow. Indeed, political dissent can be fatal; in 2011, a protest against rising food prices was met with an overzealous police response that saw nine people lose their lives; no security worker has yet been brought to justice. As recently as this year, at least two newspapers and two radio stations have been shut down for reporting that the government had plans to assassinate opposition parliamentary members.

The Public Order Management Bill is especially worrisome because it gives broader powers to security officials and imposes strict requirements for would-be organizers of anti-government gatherings. Any gathering of more than three people must gain permission from police if its intent is to criticize the government; there are no provisions for spontaneous gatherings and few restrictions on police behavior.

Civil society groups are planning to challenge the law in court, assuming they can meet to discuss their plans in the first place.

"This is Uganda’s latest restriction on space for expressing dissent and critiquing governance, which has been slowly eroded over the last few years," Burnett said. "Civil society groups working on sensitive issues such as oil revenue transparency, land, governance and human rights have increasingly faced a range of obstructions and threats to their work."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.