Simulated Mass Extinctions Speed Up Robot Evolution In A New Experiment

Life on Earth, since it first originated approximately 3.7 billion years ago, has been subjected to five mass extinction events that wiped out a huge chunk of species within a relatively short time frame. Although these events have been largely considered by scientists as bottlenecks in evolution, a new study suggests that such events could actually speed up evolution in the long term by unlocking creative, hardy adaptations.

“In particular, if extinction events extinguish indiscriminately many ways of life, indirectly they may select for the ability to expand rapidly through vacated niches,” the authors of the study, published in the journal PLOS One, said. “Lineages with such an ability are more likely to persist through multiple extinctions.”

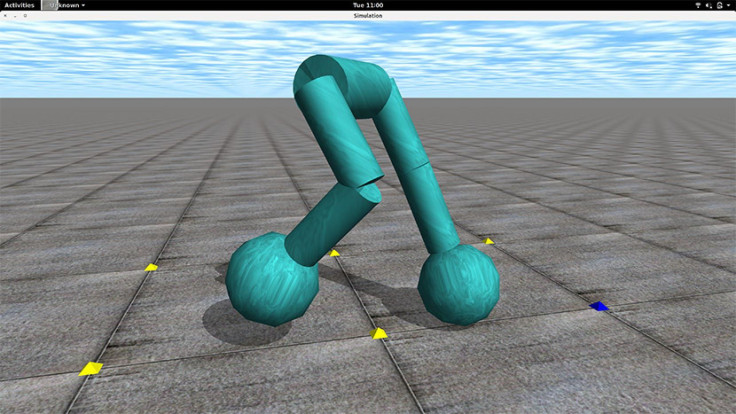

In order to test this hypothesis, the researchers utilized a computer algorithm for evolving neural networks as an evolutionary mechanism to develop a simulated robot that could walk smoothly and efficiently. Additionally, the scientists also created many different niches so that a wide range of features and abilities could appear through “self-adaptive mutation” -- similar to what is seen among living organisms.

The scientists then subjected the simulation to an event mimicking mass extinction, wiping out 90 percent of the niches.

“When an extinction event is simulated, five occupied niches are randomly selected to be spared; individuals in all other niches are discarded,” the researchers said, in the study. “Following an extinction event, organisms from the five remaining niches then repopulate the model over time.”

After hundreds of generations -- and several cycles of evolution and extinction -- the researchers discovered that the lineages that survived were the most evolvable and, therefore, had the greatest potential to produce new and better solutions to the task of walking -- as opposed to the control group that was not subjected to mass extinctions.

“This is a good example of how evolution produces great things in indirect, meandering ways,” co-author Joel Lehman, a computer scientist at the University of Texas, said in a statement Wednesday. “Even destruction can be leveraged for evolutionary creativity.”

In the real world, the findings can have implications for the field of Artificial Intelligence, including in the development of robots that can better overcome obstacles -- such as robots searching for survivors in earthquake rubble, exploring Mars or navigating a minefield -- in a more human-like manner.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.