Social Dominance May Be Hard-Wired in the Brain, Study Shows

Who dominates and gets the big cheese is all in the brain, according to new research that shows, at least in mice, social dominance may be hard-wired in the brain.

Researchers, lead by Hailan Hu, a neurobiologist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, found a region of the brain that is active in alpha mice that dominate their cagemates. When the scientists shut off the brain activity in the region, they produced subordinate mice. In a display of how fluid the response is, by reactivating the brain region, the researchers found that previously submissive mice took control in the cage.

The research appeared online Thursday in Science.

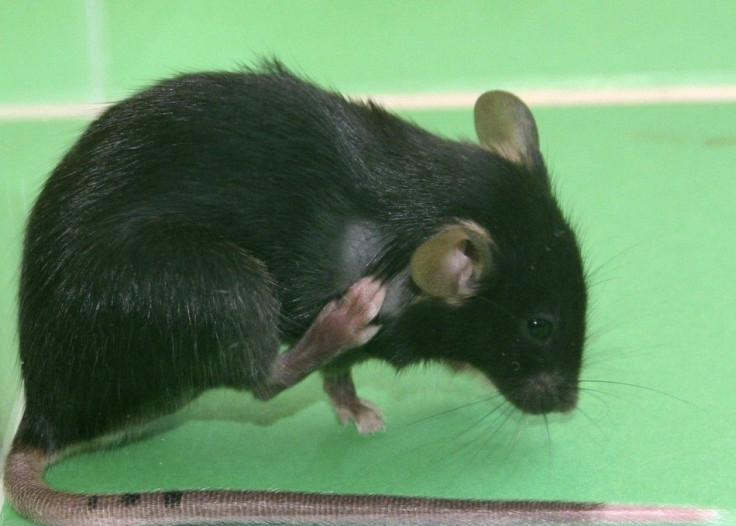

The main test for social dominance the researchers used was a stand off in a glass tube; putting two mice nose to nose in the tube and seeing which mouse pushed and which mouse cowered. The mouse that pushed the other out of the tube was the dominant one.

Not only did the dominant mouse push the other out, it also managed to dominate in other ways. Interestingly, the mouse that forced the other to retreat in the tube test also tended to gain more food, mark more territories and sing more courtship songs toward females than its subordinate counterparts, the authors said in a statement on the study. Occasionally, the dominant mouse even acted as a barber to trim off the whiskers of its cage mates.

All this social-dominating brain activity happened in the medial prefrontal cortex, a region of the mammalian brain just behind the forehead.

Previously, independent researchers found the same region lit up when friends saw each other.

The current researchers found that when they lessened the synaptic strength or the neuron connections in the medial prefrontal cortex of dominant mice, the mice became subordinate, and when they strengthened it in the subordinate mice, those mice pushed up the social hierarchy ladder.

What is really exciting about this paper is that changes within a single region of the brain can stabilize the social structure of a community-in this case mice, said Clint Penick, PhD candidate at Arizona State University, whose research includes social organization and behavior of insects. Understanding the neural networks that control dominance can help us understand how evolution shaped social behavior in the first place, said Penick, who was not involved in the study.

So what could this mean for humans?

As to implication for humans, many brain functions are highly conserved among mammals, Hu told the IB Times. So I wouldn't be surprised if the same phenomenon applies to humans.

However, Hu noted that human rank was more complex and influenced by many different factors.

In mice, it's probably mostly about one's temperament/character, Hu said in an email. But in humans, educational level, fortune, heritage, could all contribute, in addition to one's character.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.