Solar Activity Cycle Peaks In 2013: More Solar Flares Expected Later This Year

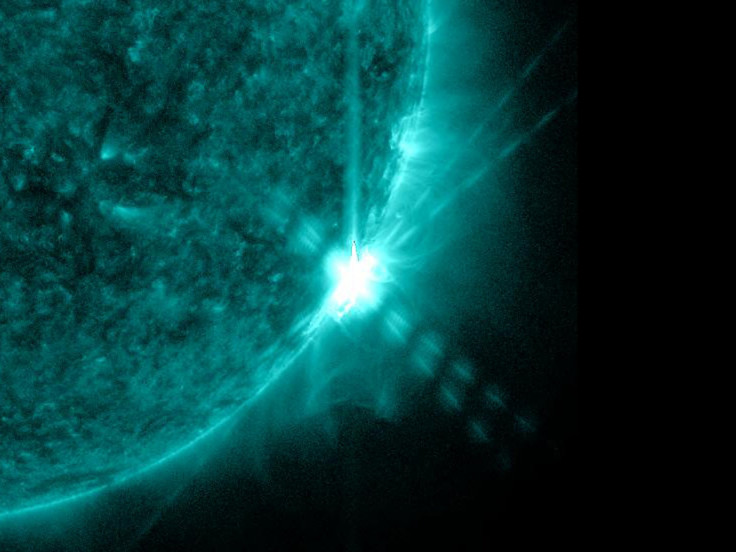

A powerful solar flare that arose on Friday is the latest reminder that our sun can be a temperamental force of nature. And we are still not quite sure how bad the consequences would be if it threw an especially violent tantrum.

Solar flares are regular bursts of radiation that can disturb Earth’s atmosphere. They’re often accompanied by coronal mass ejections, where bubbles of magnetic fields and matter – primarily electrons and protons, but with very small traces of elements like helium and oxygen – shoot out of the sun. These particle ejections are more worrisome than the radiation from flares; once trapped in Earth’s magnetic field, they can induce massive electrical currents in the ground below that can flow into power lines.

The recent flare was of middling strength, classified as an M 5.9 flare. Solar flares are classified by the brightness of the X-rays they emit. There is just one class of flare that’s stronger than M-class: X-class. While M-class flares can sometimes cause brief radio blackouts on Earth’s poles – Friday’s flare did cause a moderate one, according to NASA -- an X-class flare could potentially cause radio blackouts across the entire world, and create radiation storms in our upper atmosphere, according to the European Space Agency.

Flares are cropping up quite often in recent months, as the sun is nearing the maximum point of its 11-year activity cycle. The solar activity is expected to peak later this year, at which point there could be several solar flares a day.

Space weather has affected Earth before. In 1859, one large flare knocked out telegraph services across the Northern Hemisphere. In some cases, the operators were shocked, and machinery threw off sparks. Another hiccup came in 1989, when a coronal mass ejection led to a geomagnetic storm that caused a nine-hour power outage in Canada that affected more than 6 million people.

Some people are worried that the next big solar storm could have even more drastic effects. The worst-case scenario is an utter nightmare: Electrical grids collapse completely and can’t be restored for weeks, months, or even years. One person warning of the worst is John Kappenman, who owns the company Storm Analysis Consultants.

Electricity is the “scaffolding of modern society and if it fails, all other critical infrastructure will fail,” Kappenman told National Defense Magazine in February 2012.

If a coronal mass ejection knocked out the entire power grid, it could be catastrophic. In the blink of an eye, much of humanity is catapulted back a century or two, technologically. Massive die-offs ensue as food production dives, waste management disintegrates and water distribution and communication networks fail.

But some experts think Kappenman’s apocalyptic vision might be overwrought. In a study commissioned by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, the independent advisory group of scientists called JASON concluded that there are ways to mitigate the power grid’s vulnerability to coronal mass ejections. Finland, for example, has implemented special transformers that allow its electrical grid to deal with geomagnetic storms; after the 1989 blackout, Canada’s Hydro Quebec installed equipment designed to limit a similar situation.

“Because mitigation has not been widely applied to the U.S. electric grid, severe damage is a possibility, but a rigorous risk assessment has not been done,” the JASON report says. “We are not convinced that the worst-case scenario… is plausible.”

If there was a big solar flareup, there’s a decent chance it would occur on a side of the sun facing away from Earth and not affect us. Plus, we’d have a little bit of warning. While the flares take just under nine minutes to reach Earth (same as sunlight), the coronal mass ejections lag behind by a couple of days. At least there might be some time to prepare for the worst.

“There’s always the chance of a big storm, and the potential consequences of a big storm has everyone on the edge of their seats,” William Murtagh, a program coordinator for the the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Space Weather Prediction Center told the New York Times in March.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.