Strange Swirling Vortex Spotted High Above Saturn’s North Pole

Nearly a year after plunging into Saturn’s atmosphere and ending its mission, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft continues to provide new and intriguing information about the ringed planet. A few months back, the data it captured gave a glimpse of the Saturnian moon Titan, and now, we’re getting a good look at a strange feature present on the gas giant’s North Pole.

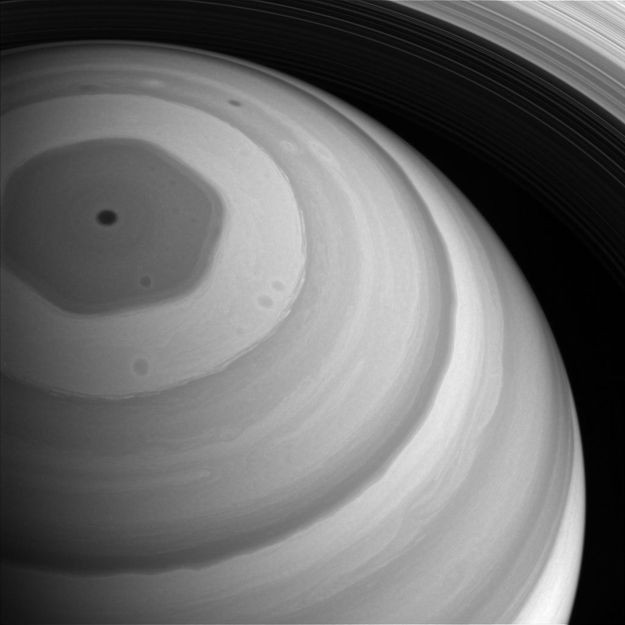

The feature being referred is a vortex — a stream of fast-moving air — swirling nearly 300 kilometers above Saturn’s cloud tops in an atmospheric layer called stratosphere.

When Cassini arrived in the vicinity of Saturn in 2004, it took a close look at the North and South Poles of the planet. During those observations, the spacecraft found a high-altitude vortex in the southern hemisphere, which was witnessing summertime, but couldn’t find similar signs in the chilly regions of the north.

The latest finding changes that observation and confirms the presence of a warm, 20,000-mile-wide vortex on the North Pole as well. This data comes from the time when the northern pole was closing in on the summer season. However, the interesting bit is the vortex seen carries a strange hexagonal shape, something that looks very similar to a cloud pattern seen at much lower altitudes in an atmospheric layer called troposphere.

"While we did expect to see a vortex of some kind at Saturn's North Pole as it grew warmer, its shape is really surprising,” Leigh Fletcher, the lead researcher behind the discovery, said in a statement. “Either a hexagon has spawned spontaneously and identically at two different altitudes, one lower in the clouds and one high in the stratosphere, or the hexagon is, in fact, a towering structure spanning a vertical range of several hundred kilometers."

The hexagon present at cloud levels was first seen by the Voyager missions in the 1980s and later analyzed by Cassini in detail. Scientists, who observed the phenomenon, confirmed it’s linked to Saturn’s rotation, but for long, Cassini’s observational techniques were restricted to the lower atmosphere. The upper region or the stratosphere had temperatures around -158 degrees Celsius, which was way too cold for its instruments to produce reliable results.

"One Saturnian year spans roughly 30 Earth years, so the winters are long," co-author Sandrine Guerlet from Laboratoire de Météorologie Dynamique, France, said in the same statement. "Saturn only began to emerge from the depths of northern winter in 2009, and gradually warmed up as the northern hemisphere approached summertime."

As this happened, the researchers got a chance to take infrared observations of the stratospheric region, which ultimately revealed the presence of the same hexagonal vortex – much higher up.

"[When] the polar vortex became more and more visible, we noticed it had hexagonal edges, and realized that we were seeing the pre-existing hexagon at much higher altitudes than previously thought," Guerlet added.

The researchers believe the vortexes present at the two poles behave very differently from each other. The whirlwind at the South Pole doesn’t feature hexagonal edges, while those at the north feature the bizarre shape and are much cooler in comparison, a fact that indicates it is still not as mature as its sibling.

"This could mean that there's a fundamental asymmetry between Saturn's poles that we're yet to understand, or it could mean that the north polar vortex was still developing in our last observations and kept doing so after Cassini's demise," Fletcher concluded. Further analysis of the Cassini data could provide more insight into two vortexes, including the reason behind the strange hexagonal shape.

The study titled, "A hexagon in Saturn’s northern stratosphere surrounding the emerging summertime polar vortex," was published Sept. 3 in the journal Nature Communications.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.