Student Loan Debt Crisis: A New Nonprofit 13th Avenue Wants An America Without College Loans

At age 12, most boys are busy with the joys of being a kid: Playing sports and spending every minute of their awake time with friends. For Eddie Triste, who's now 32, it was the age when he learned responsibility and the balancing act called life. That’s when Triste earned his first paycheck from working the fields of California’s Central Valley -- a 22,500 square-mile area considered one of the most productive agricultural regions in the world.

Triste’s parents, among a family who immigrated to the U.S. from Mexico, were day laborers, but are also big on education. His “Pops,” he says, always told him, “Son, you got a brain. Use it. Don’t be like me.”

Helping out was the norm in Triste’s community, where he said all the families struggled and there was nothing and no one to be jealous of. They all looked out for each other. That was in 1993, and after two years of field work, Triste decided he’d had enough of the subsistence life. Despite his affinity for the close-knit community, he found the struggle to get by wearing thin, to the point, he said, that he thought to himself, “Yo, this sucks.” He decided to find his own way, first by selling his mom’s delicious baked goods each morning to help out and then joining the military after graduating high school.

More than a decade later, Triste no longer works the fields. His long, skinny fingers, which used to pick fruits in the hot sun, now skim through textbook pages and tap on keyboards in air conditioned classrooms. Triste, a U.S. Army veteran, is a senior at Sacramento State University, well on his way to a sociology degree. And unlike many college graduates who have to make their own way, he'll be debt-free after graduation, partly as a result of being a beneficiary of investment from a very young nonprofit called 13th Avenue Funding, founded by a couple of Wall Street types in 2009. 13th Avenue’s only requirement is that participants agree to pay it forward and pay it back.

“Honestly, it was very hard to believe,” Triste says of his reaction when he was first introduced to the alternative higher-education funding model. “Learning how much [college] costs and with the background that I have of growing up tough, there’s not a lot of people out there who genuinely want to help with kind of no-strings-attached. So myself, I was very wary of a program that is as innovative as this. It’s like super innovative where the concept is to help students help students. [He laughs]. It was like, ‘How am I, in my level of life, where I’m still trying to get my degree and stuff like that, able to help anybody?’”

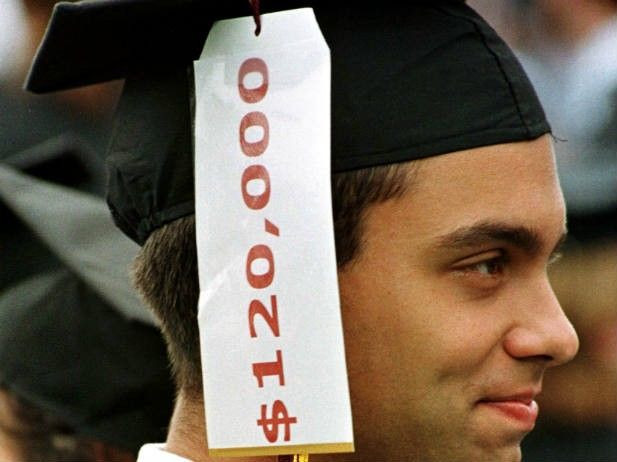

The U.S. has a student loan debt crisis that is estimated at $1 trillion. While Congress is working to lower college loan rates by tying them to the bond market, the founders of 13th Avenue think they might have an alternative answer for protecting students from unmanageable debt. Their California program makes an equity investment in education, financing students the same way venture capitalists finance companies. Those who are financially successful pay 6 percent of their income after graduation back to the fund, as stipulated by a human capital contract, until the amount they collectively borrowed is fully paid; those who end up on a less financially successful path -- say they have joined the Peace Corps or met up on hard times -- and don't meet the income threshold, pay nothing.

“Admittedly our program, because it’s different, it’s a little complicated,” Bob Whelan, CEO of 13th Avenue, says. The goal is to give a million low-income students a debt-free college education. To that end, the foundation has already received more than $1 million in pro bono work.

“The nature of our work with some of the world’s most-sophisticated businesses means we see a lot of really innovative ideas to solve major social problems across the globe,” Aaron Schoenherr, founding partner at public relations firm Greentarget, says. “When we were introduced to the 13th Avenue initiative … we were struck by the organization’s leadership and bold plans to be change agents for society. They were digging into one of the most critical issues facing students, parents and the future of our economy: access to affordable education. Assisting this project is a natural extension of the strategic communications work we do for clients every day, and it was an energizing opportunity for our team.”

The concept is simple: The founders make long-term investments into what is called a “Club,” which is owned and directed by the beneficiaries. The cooperative is built on trust among students with similar needs who sustain the program through their own success and community building.

Starting A Revolution

Conceptually, the income-contingent repayment portion of the 13th Avenue model isn’t a new idea, but it's a part of a broader effort to solve the ongoing college debt crisis in America. There’s a bill before Congress to marry this type of loan repayment with the borrower’s salary level. Oregon’s legislature voted to commission a study of the concept to see if a pilot program is worth considering. Moreover, the concept has been a best practice in Australia for more than 20 years. But the 13th Avenue model is geared toward first-generation immigrants and low-income students like Triste, and if it works, Whelan hopes it changes how higher education is financed in the U.S.

“If we get a million students as part of our national club, that would be a pretty powerful voice for school reform, for tuition reform, cost of college,” Whelan says. “These kids don’t have any voice individually, but together they do. … This idea is starting now to percolate. So, at the very least, if we can help make a contribution to the public narrative that there is a better way -- maybe it’s our way -- to finance college other than student debt, we’re helping with the public knowledge to kick it off. If we can embolden [students to talk to state representatives], if we can get a powerful revolutionary force working together that would be pretty neat.”

At its core, the program is rooted in an idea for income contingent repayment dating to 1955, when economists Milton Friedman of the University of Chicago and James Tobin of Yale University independently concluded that fixed student-loan payments made no sense because recent graduates earn less right out college and their earning potential increases over time. The model was later embraced by Presidents Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton and Barack Obama.

Why, then, is it still considered only an alternative, to the point that 13th Avenue is, for all practical purposes, plowing new ground? And why has the concept become so much better established in countries such as Australia, New Zealand and England? It may be partly because U.S. debate about such things tends to discount what happens elsewhere, says Bruce Chapman, professor of economics at the Crawford School of Public Policy at Australia National University. Chapman, who designed Australia’s student loan system about 25 years ago, says it seems odd that an idea that started in the U.S. has been more fully explored in Australia.

“So it is a very kind of peculiar thing for me to be involved in all this knowing that the intellectual basis for the income contingent loan came from the U.S. but it doesn’t exist there, but it’s kind of everywhere else,” Chapman says. “I think it’s because America is … so big and kind of rich and a world leader, and an intellectual world leader, that you probably imagine that if it’s not in the U.S. then it’s kind of is not worth looking at. When actually, this was in the U.S. intellectually and it was at Yale University.”

Making A Complex Process Simple

Rep. Tom Petri, R-Wis., sits on the House Committee on Education and Workforce and its Subcommittee on Early Childhood, Elementary and Secondary Education. He introduced an income-based repayment bill earlier this year called the Earnings Contingent Education Loans (ExCEL) Act, offering student protections by capping the interest on loans. In a piece last month for the Chronicle of Higher Education, Petri criticized the current federal student loan income-based repayment system for being too complex and cumbersome because of the amount of work borrowers endure each time their financial situation changes for better or worse.

“We try to take this concept that really has strong bipartisan roots and using it to drastically simplify the loan system in a way that really offer stronger protection to students,” Kevin James, legislative assistant to Petri, says. “We’ve created a system that has been patched over the years and has become so complicated that even fairly sophisticated borrowers have a hard time understanding it. When you look at [other] systems, they are very, very simple … where they are paying a simple percent of their income and it’s all paid automatically.”

Australia’s Chapman says when he proposed the concept there were naysayers, many of whom were political. At the time, a student loan system was new to the country; there was no precedent for lawmakers to see how an income contingent repayment plan worked elsewhere, and the government’s revenue collectors worried about how the debt would be collected. But the government decided to give it a try.

A successful income-contingent repayment system needs a minimum of three things to make it work -- things that Chapman says America also has: A system for accurate record keeping of the liabilities; a collection mechanism, preferably computerized; and a reliable way of determining the actual incomes of former students. In other words, it needs the Internal Revenue Service to be involved.

“We could’ve done it the way many countries, including the U.S., do it, which is to have the loan come from banks and be guaranteed by the government to get rid of the risk,” Chapman says. But, he says, he felt there was a better way: Collect the repayments through employer withholding like income taxes, depending on income.

“Once you make it contingent on income you solve the basic problem of not requiring people to pay when they haven’t got the money and that’s what leads to default essentially” he says.

The loan default rate in the U.S. is about 13 percent, including from debts that on paper appear manageable. Meanwhile, 85 percent of Australia’s debt comes back.

A Utopian World

13th Avenue’s Whelan looks the part of an accomplished CEO but without the stuffy air -- he’s comfortable without a tie and sometimes wears the top button on his button-down shirt loose. Compared with many of the students he helps, his educational background was privileged: He grew up in a comfortable middle-class family in Fairfield County, Conn., and sailed through Dartmouth and Stanford without “a dime of debt.”

“I didn’t quite appreciate when I graduated the no debt part of it,” he says, “but I certainly came to over the course of time.”

Whelan spent much of his career working with innovative startup companies in technology and health care, which speaks to his entrepreneurial mindset and knack for problem-solving and innovation. The 11 students in Santa Maria that his nonprofit now funds are on the opposite end of the spectrum. In their world, there's lack of financial support and financial illiteracy.

“It’s a wonder any one of them would want to go to college at all, to be honest with you,” Whelan says over the phone. “It’s just staggering. The stories we’ve heard would break your heart. But they are determined, they’re inspiring, they want to get a college education. Their career goals are as every bit as good as mine. But it’s a game that’s rigged against them.”

That’s why Whelan, his two partners and their spouses seeded $165,000 of their own money to get his model up and running. They want to give disadvantaged students a fighting chance through individual $15,000 investments with zero percent interest and a 15-year contract to repay so that another group can benefit later. Whelan and the other founders are hands off; it’s the members in the program who recruit and decide who gets the benefit. The students pick the attributes they want in their cohorts, and it’s up to them to determine who they believe will successfully adhere to the human capital contract, and perhaps, ultimately have a good enough heart to be willing to take on the debt of others who may fall on difficult times or decide on a life course that brings in an income below the $18,000 a year income threshold.

This level of freedom is empowering to Triste. After all, the people -- including Whelan -- who want to help him fill the gap in his military educational benefits look nothing like him. They don’t have the thick black hair, bushy brows, brown skin and the downturned eyes. They don’t have the unmistakable Latino accent.

“I don’t even like saying this, but I try to do what I can to help people around me because I know how hard things are but I don’t expect anything in return,” he says. “It’s just kind of like how we should be living already. … To have these outside people come in and say, ‘We do see some value in what you’re doing and we want to help, so if you want to get on board, let’s run.’ I was like, ‘Wow, that’s amazing. It’s empowering, it’s motivating.'”

Foundations that have been approached with the concept have expressed support, Whelan says, but most added that they'd be more interested once he has secured the investments of others.

“Obviously, they’ve got lots of questions about implementation, but generally it’s been enthusiastic, encouraging," Whelan says "But, ‘Come back when you’ve grown up on somebody else’s nickel, when you get real.' So we’re just a little bit too early, too … off-center when it comes to mission alignment, and that’s OK.”

If anyone can talk about the difficulty of getting investors to back a untested concept it’s Miguel Palacios, assistant professor of finance at Vanderbilt University and co-founder of Lumni, a company leading the way on human capital financing. Lumni has already funded more than 3,000 students in Chile, Colombia, Mexico and the U.S. Under its contract, students receive tuition money in exchange for a percentage of their income for a period of years. Unlike the Australian model, Lumni-sponsored students have no debt balance. They just pay whatever amount they have to during their repayment period, which can be more or less than the funding they initially received.

The human capital contract is a hard sell, Palacios says, because it’s a matter of whether the students are interested and whether investors are willing to give money.

“It’s a hard sell for investors because it’s an untried product for which the enforceability of the contract is not understood well because there is no precedent, and it’s a very long-term product,” he says. “So what you are asking from investors is take this contract which has not been tested and commit your money for [a number of] years. … Once the product becomes better known then naturally others will join.”

Welcome The Discussion

Successfully helping to enact multiple financial aid programs in California, Diana Fuentes-Michel, executive director at the California Student Aid Commission, has spent much of her life trying to increase student access to higher education. Among the problems contributing to the nation’s huge student loan debt crisis, she says, are students don’t have much discretionary income to repay their debt, costs are difficult to contain, and many students aren't financially knowledgeable.

On the cost side, California has put in place policies that have weeded out some for-profit schools that collect huge sums of federal money but have poor default and graduation rates. Though the state has a $1.7 billion grant program that helps low-income students cover tuition cost at qualified institutions, there’s more to do in terms of cost containment, she says, as well as on the loan side so that students understand the amount of debt they are taking on and what it will mean after graduation.

“They don’t think about that until graduation,” Fuentes-Michel says, “which we have to change that.”

With only a small number of students participating in the 13th Avenue model, it's difficult for Fuentes-Michel to say whether it is good or bad. But she and her colleagues welcome the discussion on the overall issue of student financing.

“We absolutely have to understand why… debt is going up,” Ed Emerson, the commission’s chief of federal policy and programs, says. “Parents and students who are signing promissory notes need to understand more what happens in two years or four years when they finish school.”

Nearly 50 percent of high school seniors in the U.S. don’t know how much they'll need to pay for college, according to a report from the Credit Union National Association, or CUNA, and more than two-thirds of students overestimate what they'll earn.

“There’s not [any] good financial literacy programs in our school right now,” Paul Gentile, CUNA’s executive vice president, says.

‘It's Wherever You Want It To Be’

Australia’s Chapman also thinks that with a human-capital contract in the mix, it will be hard for 13th Avenue to collect debt without going through a tax system. And overall, should the U.S. successfully implement an income contingent repayment plan similar to Australia’s, he sees some benefits: Students would be insured against default (which ruins their credit), and there's consumption smoothing, whereby a graduate's repayment amount is greater when income is higher.

Congressman Petri’s office believes the bill will get “ample consideration in Congress.” His legislative assistant is not familiar with the 13th Avenue program, but says “there is a lot of room in this discussion for a lot of new innovative financing models.”

And Whelan and his colleagues plan to make a lot of noise with their company, whose name came from an address used as a placeholder on an IRS application form. “Most people say, ‘What the hell is a 13th Avenue? Where is a 13th avenue?’” Whelan says. The answer, he says, is, “It's wherever you want it to be.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.