UN Says ‘Killer Robots’ Threaten Human Rights, Considers Banning Autonomous Weapons In Warfare

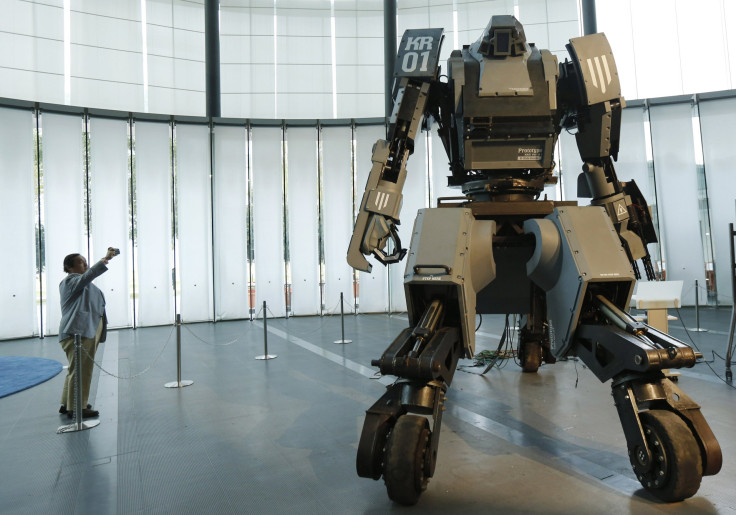

“Killer robots” have left Hollywood and entered international politics. For the first time, world leaders who are increasingly concerned with a real-life "rise of the machines" are meeting this week to consider banning the use of fully autonomous weapons in warfare.

For four days beginning on Tuesday, the U.N.'s Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons in Geneva, Switzerland, will hear testimony from representatives of its 115 member states on whether or not military robots should be allowed to select and take down their targets without direct human intervention. The multilateral talks come at a time when the international community seeks to prohibit robotic weaponry on the battlefield.

"I urge delegates to take bold action," Michael Møller, acting director-general of the United Nations' office in Geneva, told attendees, according to a UN statement. "All too often, international law only responds to atrocities and suffering once it has happened. You have the opportunity to take pre-emptive action and ensure that the ultimate decision to end life remains firmly under human control."

The convention has previously condemned the use of certain inhumane methods of warfare including land mines, laser weapons and fragment bombs.

Although we’re a long way from seeing unmanned droids à la “The Terminator” do our dirty work, a slew of countries are already developing robotic weapon technology.

According to a U.S. government report from 2012, at least 76 nations had some form of drones, and 16 countries had armed ones.

Foreign Affairs notes that in South Korea, for instance, military personnel use surveillance robots that detect targets along the border it shares with North Korea using infrared sensors, and these robots have an automatic feature that allows them to independently fire a machine gun.

Then there’s the U.S. Navy’s Phalanx gun system, which can seek out enemy fire and destroy incoming objects completely on its own.

Other countries pioneering the design and use of autonomous weaponry include Britain, Israel, China, Russia and Taiwan.

Some argue that U.S. military drone strikes, which have killed 2,400 people as of Jan. 2014, are a form of robotic weaponry.

However, drones are operated, albeit remotely, by trained human pilots. The current debate boils down to whether humans should empower robots to kill without a human ordering them to do so each time. In essence: Should a robot decide who lives and who dies?

"Killer robots would threaten the most fundamental of rights and principles in international law," Steve Goose, arms division director at Human Rights Watch, an international non-governmental organization, told the AFP. "We don't see how these inanimate machines could understand or respect the value of life, yet they would have the power to determine when to take it away."

Earlier this week, Human Rights Watch published a report that examines how fully autonomous weapons could impact human rights law, “such as upholding the principles of distinction and proportionality.”

Meanwhile, a group of Nobel Peace Prize laureates recently issued a statement, aimed to coincide with the UN talks in Geneva, in which they voiced their support for banning killer robots.

Signatories of the statement included activist Jody Williams, Archbishop Desmond Tutu and former South African President F.W. de Klerk.

“It was not that long ago that the world considered the land mine to be the perfect soldier," Paul Hannon, head of Mines Action Canada, said in a televised statement in April. “It is now banned because of the humanitarian harm it has created. Canada led the movement to ban that weapon; it is one of the most successful international treaties of our era.”

You can follow live updates of the convention in Geneva through the "Stop Killer Robots" Twitter account here.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.