In US, Social Mobility Is Casualty Of Income Inequality

Upward income mobility has decreased to such a point that the United States appears to have the highest rate of income inequality in the industrialized world, according to the non-partisan Congressional Research Service.

"Empircal analyses estimate the United States is a comparitvely immobile society, that is, where on starts in the income distribution influences where one ends up to a greater degree than in several advanced economies," the report states, suggesting the U.S. is no longer, if it ever was, a nation where the poorest can feasibly lift themselves up by their bootstraps.

If income were equally distributed, each quintile (or fifth) of households would account for 20 percent of total income. The poorest quintile has long since accounted for far less than its proportionate share, barely budging from about 4 percent in recent decades, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Meanwhile, since 1968 the middle class (defined as the three middle quintiles, or 60 percent of households) has seen its total income share decrease steadily, while those among the top-fifth of earners – particularly the top 5 percent – have seen their incomes skyrocket. For instance, the top 5 percent held 22.3 percent of the nation’s wealth in 2011, up from 16.3 percent four decades earlier.

Rich People Have Rich Parents

The advantages offered by an affluent lifestyle clearly influence an individual’s chances for economic mobility, the CRS reports. According to an analysis of empirical data, the study authors estimate there is a positive relationship of about 0.5 between a parent and adult income – meaning, the children of parents with above-average salaries are more likely, on average, to also bring in high incomes.

So: Half the economic advantage the children of well-off families enjoy comes from having been born into wealthy families in the first place. On top of that, the chances of adults moving up from their initial income economic position has decreased or remained stagnant in recent decades, which is of particular concern since most Americans still believe economic mobility in the U.S. is completely within their reach.

“Americans may be less concerned about inequality in the distribution of income at any given point in time partly because of a belief that everyone has an equal opportunity to move up the income ladder,” reports the CRS. “A review of the literature suggests that Americans’ perceptions about their likelihood of changing position in the income distribution may be exaggerated.”

Those within the three middle quintiles (the middle class) will, statistically, experience some economic mobility. But according to a study by the Pew Economic Mobility Project, 43 percent of children whose parents were born in the bottom quintile remained at the bottom when they became adults. In contrast, 40 percent of children born to parents at the top quintile were also at the top as adults. The study compared intergenerational mobility rates between 1984 to 1994 and 1994 to 2004.

Other advanced economies see considerably more intergenerational income change, according to a European study cited by the CRS, which cites several nations, including Germany and Scandinavian countries, where the income of parents is less likely to influence their children’s economic future.

The perception of economic mobility is likely positive because rates of mobility among the middle three quintiles of the population – the middle and upper-middle class – are similar to those in comparable economies. But that doesn’t account for the enormous financial gains experienced by the top fifth, which has increased from 44.1 percent of total U.S. income in 1980 to 51.1 percent in 2011.

Wage inequality is not the only reason that income inequality has been on the rise for decades (although the wealthy have seen their wages increase at a far higher rate than the middle class and poor).

Congress’ longstanding partisan battles about policy issues such as instituting a more progressive tax code, the tax treatment of capital gains and inheritance, and the expansion of social welfare benefits (like food stamps) in recent years have not usually ended with a win for the nation’s poor.

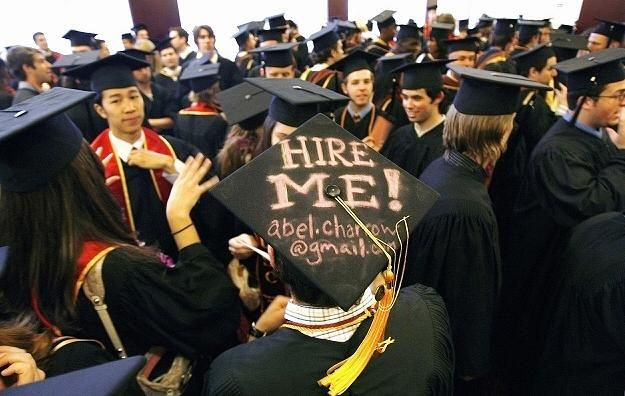

Education Gap Creates More Inequality

The philosophical battle over how to achieve economic growth and social mobility – with Republicans calling for self-reliance and Democrats pushing for more investments in social safety net programs – has escalated to a point that conservatives have resisted attempts to direct more investments in programs such as early childhood education and college tuition aid. The CRS reports those initiatives “arguably promote equality in the opportunity to move up the income ladder, which an increasingly unequal distribution of income may suggest a lack of and which may itself curb the potential productive capacity of the economy.”

That appears to be the case, because an education gap is one of the main reasons commonly offered to explain the nation’s widening income inequality. Some studies suggest that as technology advances, lower-income workers do not have the skills or educational requirements to keep up with changing labor demands. The need for “high-skilled” workers (e.g., those trained in engineering or information technology) has risen, while the need for low-skilled and middle-skilled workers has decreased – one of the casualties of globalization.

Although many still firmly believe, and constantly argue, that Americans have an equal opportunity to move up the economic ladder, the study authors concluded that opportunity is far from “equal.”

“It also appears that going from rags to riches is relatively rare; that is, where one starts in the U.S. income distribution greatly influences where one ends up,” the report concludes.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.