Were Affordable Care Act Co-ops Doomed To Fail? As Insurers Fold, Shortfall In Little-Known Risk Corridor Payments To Blame, States Say

It was only six weeks ago that the horizon appeared bright for Colorado HealthOP. The health insurance cooperative had cash, competitive rates and booming membership. Even though it faced many of the usual struggles of a startup, some predicted it might even turn a profit in 2016. But on Oct. 1, the federal government announced that it would pay out a fraction of a fund called the risk corridor, depriving the co-op of some $14.2 million in expected funding. Shortly after that, another notice came from state regulators informing Colorado HealthOP that it would be forced to shut down.

Colorado’s co-op was hardly the only one.

Twelve of the 23 health insurance co-ops created under the Affordable Care Act have announced -- many of them in the last month -- that they will close by 2016. While these co-ops face unique barriers as start-ups in a cutthroat health insurance industry, co-op leaders and outside experts have homed in on one factor in particular that triggered this cascade of demises: the Oct. 1 news that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) would dole out just 12.6 percent of payments owed as part of its risk corridor program.

“That totally turned our situation upside down,” Chuck Holum, Colorado HealthOP’s board president, said. “The fact that we didn’t get the full amount of the risk corridor money that we’d been promised – and it was a fundamental part of this program – was the reason we were forced out of business.”

The #ACA CO-OP Program: Barriers and Opportunities http://t.co/K5NjRr1VCI pic.twitter.com/3IjPypgc1s via @commonwealthfnd #healthreform #AHLA15

— AHLA_HCR (@AHLA_HCR) March 17, 2015

Co-ops, an acronym for Consumer Operated and Oriented Plan, were launched as part of the 2010 Affordable Care Act to help spur competition, increase consumers’ options and lower premium prices for health insurance. The federal government initially allocated $6 billion in loans to help these start-ups take off, although that amount was ultimately reduced to $2.4 billion. Still, co-ops generally received tens, sometimes hundreds of millions of dollars, to create networks of doctors and attract consumers in what is one of the most volatile, competitive and difficult industries to break into.

“It is extremely hard to start a new insurance company and sustain it,” Deep Banerjee, the director of financial Services ratings at Standard & Poor’s in New York, said. Such companies need hefty capital, in order to both obtain approval from regulators and survive losses that are inevitable in their early years, he pointed out. The co-ops created under the Affordable Care Act also contended with unique challenges.

They primarily sold plans through exchanges created by the Affordable Care Act, which drew many customers who previously lacked health insurance, some of whom were sicker and thus more expensive. Those new customers had no history of health insurance, so start-ups struggled to figure out how much to charge them, yet because one of their main purposes was to offer better rates than existing insurance companies, they often charged too little to cover their costs.

“There just wasn’t enough capital for them to survive as a startup company in a highly competitive environment,” Banerjee said. “They just didn’t price for enough premiums to cover the claims,” he added.

The federal government’s risk corridor program was supposed to help offset the costs of taking sicker patients and help mitigate insurers’ risk by redistributing funds. It didn't work out that way. For 2014, insurers requested $2.87 billion in payments from the fund, but they paid only $362 million into the pool. Yet co-ops had budgeted with the expectation that they would receive far more.

HHS announced risk corridor payments for insurers -- only getting 12.6% of request for 2014: pic.twitter.com/H6jjiJsXvI

— Drew Armstrong (@ArmstrongDrew) October 1, 2015

“That was the last nail in the coffin,” Banerjee said.

A Slew Of Closures

Kentucky Health Cooperative announced Oct. 9 that it would cease to offer health coverage in 2016, citing the fact that it had expected to receive $77 million in risk corridor reimbursements but had learned it would instead receive just $9.7 million. The news changed the co-op's accounting overnight, because risk corridor money is legally allowed to be listed as accounts receivable -- assets that the co-op expects to be paid -- Sharon Clark, Kentucky’s insurance commissioner, said.

“They [the Kentucky Health Cooperative] were solvent on paper until we received that notice that they were not going to receive the entire amount,” Clark said of the risk corridor funding. “It threw the co-op into a financial situation where it was mandatory that the department step in and take action.”

Now, the Kentucky Health Cooperative is in rehabilitation. The roughly 51,000 people who bought insurance through the co-op will have to buy new insurance plans elsewhere in order to get coverage in 2016, and Clark said the state was working to help people switch. “We’re doing everything we can in Kentucky to make this as seamless as possible,” she said.

Kentucky Department of Insurance filed petition to place KY Health Cooperative into rehabilitation, will oversee day-to-day operations.

— Joe Sonka (@joesonka) October 29, 2015

Other health co-ops announced in October that they, too, would shut down by 2016, pointing to the shortfall in federal risk corridor funding as the final straw.

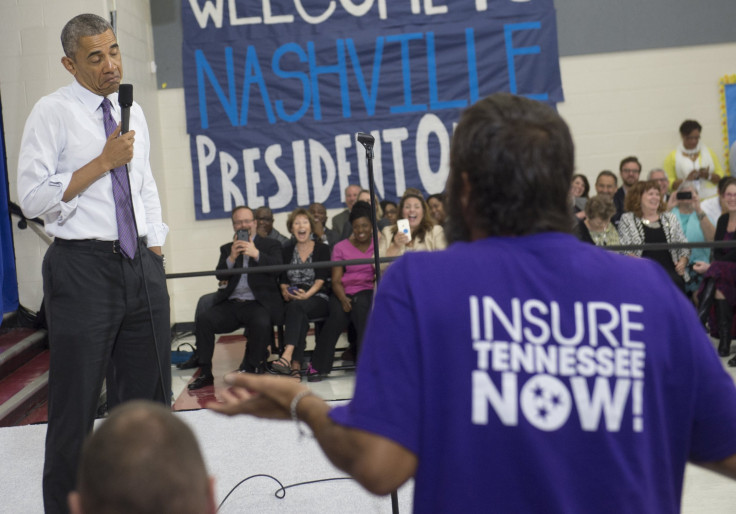

Tennessee’s Community Health Alliance Mutual Insurance Company, which decided to close Oct. 14, had struggled since 2014 to attract consumers, garnering just 9 percent of its project enrollment of more than 25,000 for that year as well as a net loss of $22 million by year’s end. In January 2015, it froze enrollment. It had been tentatively slated to unfreeze in time for open enrollment beginning Nov. 1, until it learned that that risk corridor program payments had been slashed.

“The inability of CMS’ Risk Corridor Program to be fully funded created a net worth deficiency for CHA [Tennessee’s co-op] which ultimately could not be cured,” Julie McPeak, commissioner of the Tennessee Department of Commerce and Insurance said Thursday during a house subcommittee hearing titled, “Examining the Costly Failures of Obamacare’s Co-op Insurance Loans,” according to her prepared remarks.

Arizona, Oregon, Michigan and South Carolina were among other states whose co-ops announced in October that they would close down by 2016. An estimated 740,000 people nationwide will be affected by the closures, the Washington Post reported.

A Cutthroat Market

Other factors arguably contributed to these co-ops’ demise, experts pointed out. As new players, they weren’t always able to advertise themselves to customers and compete with well-known insurers. In fact, they were barred from using government funding to do so.

“There's no single reason why the failed co-ops were unsuccessful,” the National Association of Insurance Commissioners said in a statement. “Co-ops were new companies taking on unknown risk pools and operating in a very competitive marketplace,” it noted, while “the enrollment was higher or lower than expected in some states.”

“The co-ops struggled from the beginning just making it known that they exist and that they were a viable option,” Shana Charles, an assistant professor in the department of health sciences at California State University, Fullerton, said. “When it comes to health insurance, people are risk averse to try new companies. There has to be a good and compelling reason to try something new, a company you haven’t heard of before,” she said.

CO-OP members will need to purchase different health coverage for 1/1/16. Use @C4HCO to buy by 12/15/15. #FAQs http://t.co/VWCE87WS8q

— Colorado HealthOP (@COHealthOP) October 16, 2015In a way, the co-ops were disadvantaged from the start, compared to bigger insurance companies, analysts said. Even before it became clear that risk corridor payments would be far less than expected, some co-ops, like those in New York and Iowa, had announced plans to close down.

Still, some co-ops had been faring well, even as they contended with the usual growing pains of startups. “We were still a company that had to follow our finances very closely. It’s not like we had huge piles of reserves,” Chuck Holum, of Colorado HealthOP, said. But the co-op had been on its way to becoming something – until it was stopped in its tracks. “It is a huge mistake,” Holum said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.