What Are Solar Campfires? Mini Flares Shed Light On Sun's Coronal Heating Mystery

KEY POINTS

- The Solar Orbiter captured stunning close-up images of the sun last year

- It captured a phenomenon, dubbed solar "campfires"

- These mini solar flares could "contribute to the heating of the corona"

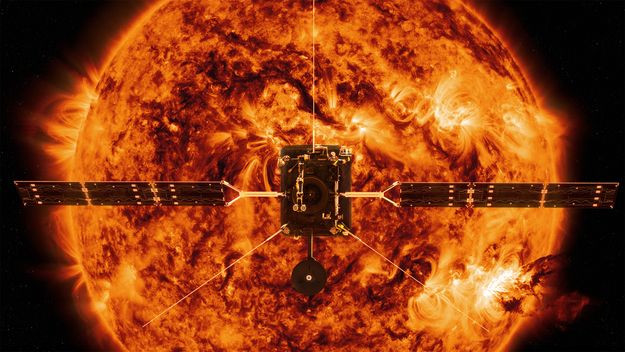

The European Space Agency (ESA) and NASA's Solar Orbiter spotted "campfires" on the Sun last year. Scientists are now getting a better idea as to how these solar flares can help unveil one of the most mysterious features of our host star.

There's something rather strange about the sun that scientists have been trying to understand. Although its surface is cooler than its center, with its temperature at just 5,500 degrees Celsius (9,900 degrees Fahrenheit), its atmosphere, called the corona, is much hotter and runs up to a million degrees (1.7 million degrees Fahrenheit).

This seems to counter logic as something with a hot center would become cooler as one goes further away from it, the ESA said in a news release.

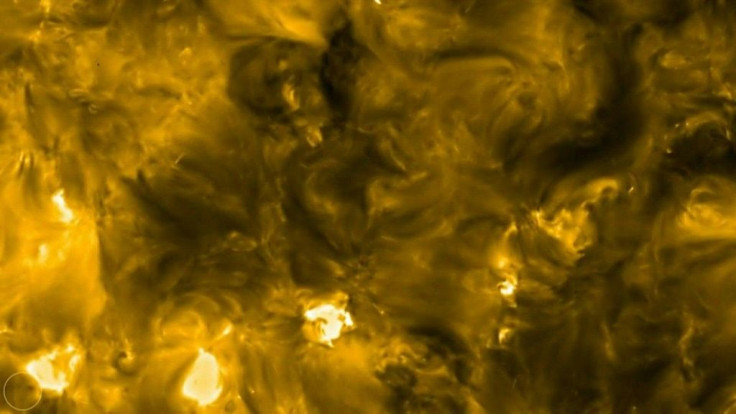

In 2020, the Solar Orbiter satellite snapped incredible close-up pictures of the Sun, which revealed a phenomenon known as solar campfires. Lasting just 10 to 200 seconds each, these are like mini solar flares that happen close to the surface of the Sun.

These can be "million or billion times smaller" than the solar flares we know, David Berghmans of the Royal Observatory of Belgium said at the time. However, they occur much more frequently than the larger solar flares people are more familiar with, the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) noted in a news release. The images taken by the Solar Orbiter showed around 1,500 such flares.

So do these solar campfires have something to do with the corona's mysterious heating? At the European Geosciences Union's (EGU) General Assembly on Tuesday, a team of researchers presented their findings, pointing to solar campfires as the potential source of the heating.

For their study, which was accepted for publication at the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics, the researchers created computer simulations to study solar campfires.

"The model generated brightenings just like the campfires. Furthermore, it traces out the magnetic field lines, allowing us to see the changes of the magnetic field in and around the brightening events over time, telling us that a process called component reconnection seems to be at work," study co-author, Dr. Hardi Peter of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, said in the news release.

Reconnection is the process by which magnetic field lines "break and then reconnect," the ESA explained, noting that each time this happens, they release energy.

The energy released from the "brightenings" may be enough to explain the temperature of the corona, said Yajie Chen, study first author and a Ph.D. student at Peking University in China.

The campfires are driven by component reconnection whereby almost parallel field lines break & reconnect, releasing energy when they do so. The model shows this could be enough to maintain the temperature of the solar corona predicted from observations https://t.co/O7ZKr4rBuW pic.twitter.com/9lb8mrk0J1

— ESA's Solar Orbiter (@ESASolarOrbiter) April 27, 2021

"Based on our study, we propose that the majority of campfire events found by EUI (Extreme Ultraviolet Imager) are driven by component reconnection and our model suggests that this process significantly contributes to the heating of the corona above the quiet Sun," the researchers wrote.

Though further research is required on the topic, the recent findings are quite impressive, especially considering the fact that the Solar Orbiter, including the EUI that captured the first images of the campfires, isn't even in service yet. In fact, the spacecraft is still in its "cruise phase" wherein the focus is on instrument calibration.

When it captured the images, it was at about halfway between the Earth and Sun. Its regular measurements will only begin later in the year, the MPS said.

"How fantastic to already have such promising data that may provide insight into one of solar physics' greatest mysteries before Solar Orbiter has even begun its nominal science phase," said Daniel Müller, Solar Orbiter project scientist at the ESA. "We're looking forward to see what missing details Solar Orbiter – and the solar community working with our data – will contribute to solving open questions in this exciting field."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.