Afghanistan Opium Production At Record High Amid Instability, Slowing Economy And High Demand

Opium production hit an all-time high in Afghanistan last year, and the trend doesn’t look like it will reverse any time soon, according to a new report from the special inspector general's office.

Increasing economic and political instability in a country that produces 80 percent of the world’s opium supply has only created more incentives for local farmers to grow poppies, and opportunities for Taliban traffickers to cash in on a growing global demand.

“As you know, the narcotics trade poisons the Afghan financial sector and undermines the Afghan state’s legitimacy by stoking corruption, sustaining criminal networks, and providing significant financial support to the Taliban and other insurgent groups,” John F. Sopko, the special inspector general for Afghanistan reconstruction, wrote in an Oct.14 letter to U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry, Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel, Attorney General Eric Holder and Rajiv Shah, administrator of the U.S. Agency for International Development, which administers civilian foreign aid.

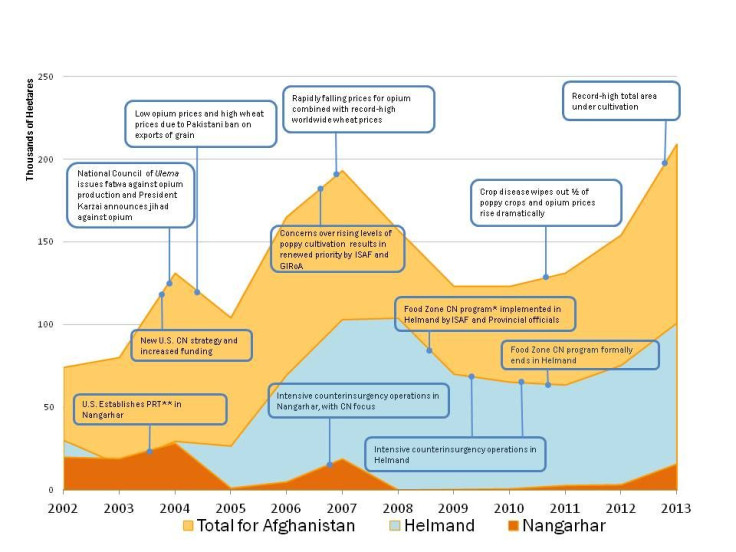

“Despite the significant financial expenditure, opium poppy cultivation has far exceeded previous records,” Sopko wrote, adding that the increase is due to “relatively high opium prices and the rise of an inexpensive, skilled and mobile labor force.”

The U.S. has spent more than $7.7 billion on counter-narcotics efforts in Afghanistan in recent decades, Sopko said in a recent report that also explained how the opium industry expanded from $2 billion to $3 billion between 2012 and 2013.

But beyond these billions, a thriving global supply chain has created a lucrative international business.

“The main profits on Afghan drugs are made outside of Afghanistan, as opium and its derivatives go to Europe,” Thomas Ruttig, co-director of the Afghanistan Analysts Network, an independent think tank based in Berlin and Kabul, said. Ruttig added that they’re moving in higher amounts toward Russia, India and Iran as local consumption is also increasing.

Traditionally, Afghan opium products such as heroin are transported through the Balkan region to lucrative markets in Europe. But the United Nations recently reported an increase in trade with South-East Asia and Oceania, a relatively new development stemming from shrinking markets in the West.

But even the relatively small profit local farmers make is a substantial incentive to keep going, and a lagging economy has only made opium a more appealing crop for farmers.

“With a shrinking licit economy, the weight of the drug industry grows automatically,” Ruttig said.

Afghanistan is facing an economic downturn due to the withdrawal of NATO combat troops, a lack of reforms slowing down foreign investment, capital flight due to insecurity and high levels of political uncertainty, which came to a head during the latest six-month electoral deadlock. Switching to the drug business, Ruttig said, is often a coping mechanism for farmers to compensate for losses.

“There are no other income sources in Afghanistan that produce the kinds of profits that narcotics overall, especially opiates, can,” said Jodi Vittori, Afghanistan adviser Global Witness, a London-based organization that investigates the economic networks behind conflict around the world.

“While the farmers themselves earn an incredibly tiny portion of the proceeds from growing opium, it is still one of the better sources of incomes around.”

Opium can be stored for years and sold whenever a family needs cash, almost like a savings account, which is especially important given the low confidence in the country’s banking system, fraught with scandals like a 2010 Ponzi scheme involving the Kabul Bank.

Roughly 44 percent of farmers surveyed by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime said they were cultivating opium because of its high sale price and rate of income to land use. But it takes more than producer interest to keep production going.

“While the actual farmers get the smallest slice, that’s still an important slice in a desperately poor economy,” Vittori said. “The further up the supply chain one goes, the greater the profits, from those who process the drugs to those who smuggle them across the numerous borders to the customers, to the wholesalers, and to the street level dealers.”

And high levels of corruption in the country make it easier for traffickers to move without punishment, as long as money gets into the right hands.

“There are very high profits to be made from buying raw opium, processing it, and smuggling it and there is little chance of getting caught,” Vittori said.

Afghanistan ranks 175th on Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index, and the issue has been a top priority for its new president, Ashraf Ghani. And in farther-flung areas that are less covered by the government, members of insurgent groups such as the Taliban are able to thrive.

“The Taliban’s involvement with the narcotics trade has increased steadily over time,” Colin Clarke, a threat finance expert at the Rand Corp., said. He explained that experts have known about their involvement -- which has been escalating -- for more than a decade.

The United Nations reported in the summer that Helmand province, the top opium-producer in the country with at least 100,000 hectares of cultivated land, was also the main source of Taliban funding. Afghan officials told Reuters that most of the province’s farmers also pay a 10 percent tax to Taliban members.

From there, the money can be reinvested in ordinary companies to hide the profits and possibly the shipments themselves, according to Clarke.

"The Taliban launders money from its drug proceeds through myriad pipelines, including commodities, hawala money transfers, overpricing goods, real estate, shell businesses and the stock exchange," he said.

And its easier for these groups to manipulate the markets in areas far from government control.

“As found elsewhere in the world, the illegal drug trade is strongest in areas where security and rule of law are weak,” the U.S. State Deptartment wrote in a recent briefing on the topic.

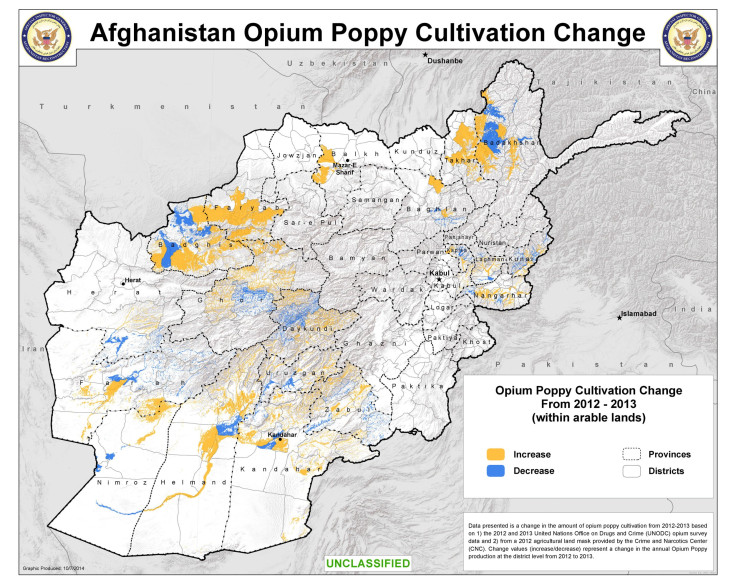

The eastern province of Nangarhar was once considered a success for counter-insurgency efforts and declared “poppy-free” by the United Nations in 2008. But between 2012 and 2013, it has seen a fourfold increase in poppy cultivation, according to the special inspector general's report.

Afghan officials are calling on American agencies to continue working in the country, but perhaps take on different strategies, since their current methods haven’t exactly been as successful as planned, according to a recent audit.

“Given the severity of the opium problem and its potential to undermine U.S. objectives in Afghanistan, I strongly suggest that your departments consider the trends in opium cultivation and the effectiveness of past counternarcotics efforts when planning future initiatives,” Sopko wrote in the report.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.