Antarctic Ozone Hole Slightly Smaller Than Average This Year, NASA Says: Has The Healing Begun?

The ozone hole, the annual thinning of the protective ozone layer in Earth’s stratosphere over Antarctica, was slightly smaller than average this year compared to its size in recent decades, NASA said on Friday.

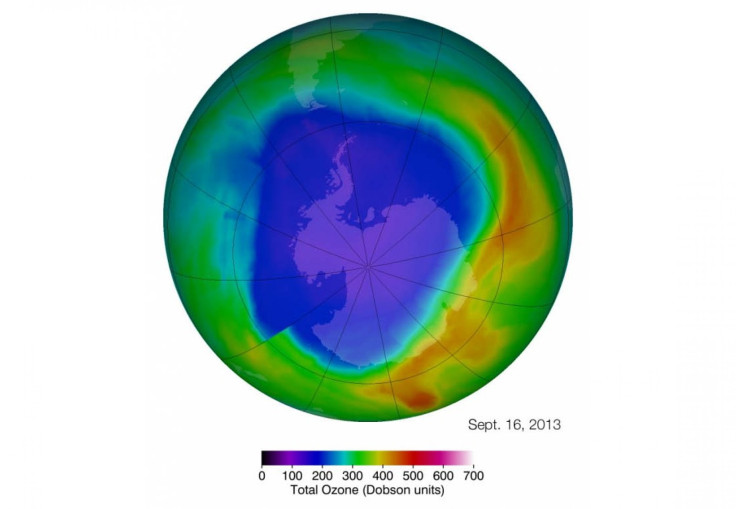

The seasonal depletion of ozone begins during the Antarctic spring, which spans from August to September. After examining this year’s satellite data, NASA found that the September-October 2013 average ozone hole size was 8.1 million square miles, while the average size measured since the mid-1990s, when the annual maximum size stopped growing, is 8.7 million square miles.

However, according to NASA, it is too early for scientists to determine whether a "healing process" of the hole has begun.

“There was a lot of Antarctic ozone depletion in 2013, but because of above average temperatures in the Antarctic lower stratosphere, the ozone hole was a bit below average compared to ozone holes observed since 1990,” Paul Newman, an atmospheric scientist and ozone expert at NASA, said in a statement.

The largest single-day ozone hole of this year was recorded on Sept. 16 when the maximum area reached 9.3 million square miles, which is about the size of North America. The single-day maximum area since the mid-1990s was reached on Sept. 9, 2000, measuring 11.5 million square miles.

In 2012, the average area covered by the Antarctic ozone hole was 6.9 million square miles, which was considered to be the second smallest in the last 20 years, with scientists attributing the change to warmer temperatures in the Antarctic lower stratosphere.

The Antarctic ozone hole forms when the sun begins rising again after several months of winter darkness. While the polar-circling winds keep cold air trapped above the continent, sunlight-sparked reactions, involving ice clouds and chlorine from manmade chemicals, begin eating away at the ozone layer, which acts as Earth's natural shield against ultraviolet radiation, which can cause skin cancer.

Overall atmospheric ozone no longer is declining as concentrations of ozone-depleting substances have gradually declined as the result of the 1987 Montreal Protocol, an international agreement regulating the production of certain chemicals.

NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) have been monitoring the ozone layer from the ground and with a variety of instruments on satellites and balloons since the 1970s.

According to scientists, the ozone hole phenomenon, which began making a yearly appearance in the early 1980s, is not expected to return to its early global levels until 2050, and could even be completely eliminated by 2065.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.