Are Eyewitnesses Right? DOJ Issues New Guidelines For Identifying Suspects

It's a standard part of many criminal investigations familiar to fans of police procedurals: the eyewitness, with police by her side, chooses the suspect out of a lineup and helps the cops get the bad guy. This may seem like a foolproof way to ensure the right person is arrested for a crime, but the Department of Justice has become worried too many good guys are getting selected by mistake.

The DOJ has issued new guidelines for securing eyewitness identifications. The announcement on Friday came in response to a growing body of research suggesting criminal investigators can inadvertently influence eyewitnesses choosing suspects out of a lineup.

The guidelines, the first the DOJ has issued for eyewitness identification, recommended law enforcement personnel investigating cases should not be the ones to administer photo lineups to eyewitnesses. The DOJ wants eye witnesses to look through lineups with officers who have no knowledge of the case in question. This “double-blind” standard, which is widely used in scientific studies, prevents administrators from influencing eyewitnesses, either intentionally or accidentally.

The new policy apply to the FBI, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) and the U.S. Marshals Service, as well as DOJ prosecutors.

“Eyewitness identifications play an important role in our criminal justice system, and it’s important that we get them right,” said Justice Department Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates in a statement. "It is therefore crucial that the procedures law enforcement officers follow in conducting those identifications ensure the accuracy and reliability of evidence elicited from eyewitnesses.”

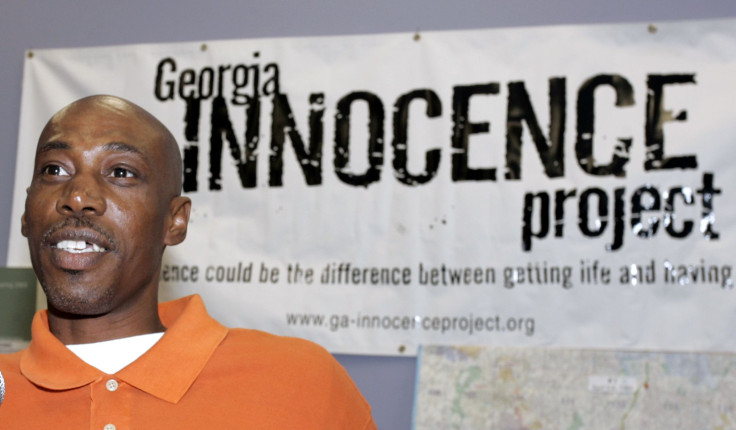

False eyewitness identifications played a role in more than 70 percent of convictions overturned by DNA testing, according to the Innocence Project, a nonprofit dedicated to exonerating the wrongfully convicted by using DNA technology. In 2014, the National Academy of Sciences published a report on eyewitness identifications that recommended many of the changes outlined in the DOJ report.

“The psychological influence of a police officer’s body language as an eyewitness views a lineup…are so subtle that studies are only beginning to reveal their effects,” two of the report’s authors, Thomas Albright and Jed Rakoff, wrote in a 2015 Washington Post opinion piece on the need to reform eyewitness identification.

Richard Rosario is free! "I've been in prison for 20 years for a crime I didn't commit." https://t.co/T2lKQJKjmF pic.twitter.com/Q7th5IS8Ci

— The Innocence Project (@innocence) March 23, 2016

Law enforcement officers sending signals and cues isn’t just a problem for eyewitnesses making an identification, it’s also been shown to be a problem for other officers – canine ones.

A 2011 Chicago Tribune analysis found that only 44 percent of alerts given by drug-sniffing dogs during automobile stops led to officers discovering drugs or paraphernalia. But when searching cars with Hispanic drivers, the dogs were more likely to falsely indicate the presence of illegal drugs. In those searches, the dogs' accuracy fell to 27 percent.

Are police dogs biased against Hispanics? No, dog experts say. But they do react to signals and cues from their handlers, who may have unconscious, or conscious, biases against Hispanic drivers.

"Is there a potential for handlers to cue these dogs to alert?" Paul Waggoner of Auburn University's detector dog research program asked the Tribune. "The answer is a big, resounding yes."

The new guidelines also addressed the problem of fluctuating degrees of confidence in eyewitness identifications. Confidence in an eyewitness identification can increase over time, which can lead to eyewitnesses asserting more confidence in their identifications from the witness stand, months or years after the crime, then during the lineup process.

To address this problem, the new guidelines suggested investigators film eyewitnesses choosing pictures out of a photo lineup, as well as document the confidence of the witnesses in their choice at the exact moment they make their selection.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.