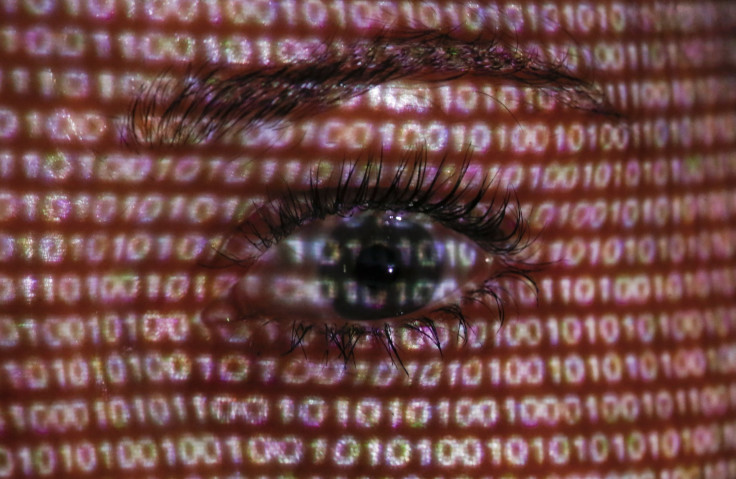

Australia Authorizes Data Retention Law, Requires Telecom Companies To Store Data For 2 Years

Both of Australia’s major parties voted to pass a mandatory data retention plan, bringing the contentious proposition into law on Thursday. The new legislation, which passed 43 to 16, requires all telecommunications providers to keep phone and Internet records for two years, and provide government agencies access to the stored data.

The Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Amendment (Data Retention) Bill 2015 mandates the tracking of call records, assigned IP addresses, location information and billing information, among other data, and empowers security agencies to access them without a warrant. Both the ruling Liberal Party of Australia and the opposition Australian Labor Party came together to kill over a dozen proposed amendments from the Australian Greens party, and several others from independents.

Greens Senator Scott Ludlam said the legislation “entrenches a form of passive surveillance over 23 million Australians,” according to The Guardian. “The ALP [Australian Labor Party] has caved into [Prime Minister] Tony Abbott’s self-interested fear campaign and supported the bill,” Ludlam said. “You failed to turn up. You will be judged for that … We will remember this in 2016 and we will not let others forget.”

The amendments would have kept the data within Australia, required the use of warrants to access them and limited the storage period to three months instead of the current two-year period. Several providers already use such measures, but the specific data stored, and the period of time the information is preserved for, vary between companies.

However, the Labor party passed an amendment that protects the data of journalists more stringently, requiring authorities to get a warrant to access their data in order to protect private sources and whistleblowers. A “public interest advocate” will argue on behalf of the journalists in each case, but the journalists in question will not be informed that their data is being requested for.

The government has not revealed how much the plan will cost to set up, leading to criticism from telecommunications companies. It is also unclear how much of the total cost will be borne by the companies themselves, though the government has said it will make a “substantial contribution.”

Australia’s Attorney General George Brandis praised the decision, and said that metadata comprised “the basic building block in nearly every counter-terrorism, counter-espionage and organized crime investigation.”

He said that many ongoing operations depended on data that needed to be provided voluntarily by companies, and a mandatory standard ensured fairness. “A victim’s right to justice, and agencies’ ability to solve crimes, shouldn’t depend on which service provider is used by the victims and perpetrators,” he said, according to the Guardian.

But independent Senator Nick Xenophon, one of the bill’s main opponents, warned in a tweet that the law was “like a python - slowly suffocating investigative journalism and free speech.”

The mandate to retain data does not begin immediately, and companies have until 2017 to finish implementing the necessary architecture to adhere to the new law.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.