Bank Breakups: Citigroup Forced To Put Breakup Study Proposal To Vote

Talk of big bank breakups is back. Presidential candidate Sen. Bernie Sanders has made splitting up banks a campaign rallying cry. Newly appointed Minnesota Federal Reserve President Neel Kashkari made waves Tuesday by calling the largest financial institutions “still too big to fail” and suggesting “bolder, transformational options” to address them.

Next up in the conversation: shareholders at Citigroup.

The Securities and Exchange Commission ruled this week management at the nation’s third-largest bank by assets must float a shareholder proposal that, if approved, would require Citigroup to study options for breaking up and to report the findings within 10 months.

According to the language of the proposal, the company would have to appoint a committee “to address whether the divestiture of all noncore banking business segments would enhance shareholder value.” Noncore divisions include any part of the company outside of its federally insured retail banking center, Citibank N.A.

In other words, Citigroup would have to tell investors whether its parts are more valuable than the company as a whole.

The man responsible for the proposal is Bartlett Naylor, a financial policy advocate for the Washington watchdog group Public Citizen. Last year Naylor pushed through a similar proposal for Bank of America to weigh the pros and cons of splitting up. Although shareholders rejected the proposal, the bank later hired a firm to conduct the study, Naylor told International Business Times.

Naylor’s motivation for seeking the breakup talks are twofold. “From a pure shareholder point of view, the company would be worth more broken up,” Naylor said. That is, if Citigroup sold all its assets and paid off its debts, it would have more cash than its shares are currently worth.

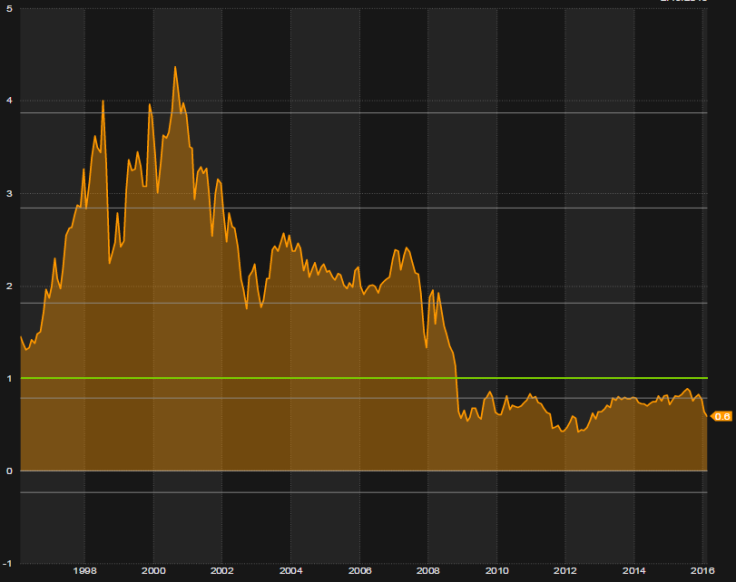

Currently, Citigroup’s price-to-book value — the ratio of its market capitalization to its total accounting value — stands at 0.59. Put another way, the company is worth 70 percent more than its stock price suggests.

Then there’s the issue of systemic risk that Sanders and Kashkari have recently highlighted. “From a public policy point of view the bank is too big to manage,” Naylor said, pointing to multibillion-dollar settlements stemming from Citigroup’s mortgage-related misdeeds in the runup to the 2008 financial crisis.

As Bank of America did last year, Citigroup attempted to keep Naylor’s proposal off the ballot at its 2016 shareholder meeting. Companies that want to avoid potentially unflattering resolutions can ask the SEC for permission to reject them. After a lengthy back-and-forth over the merits of the proposal, the SEC will either grant a “no-action” letter allowing the company to block the vote from taking place or let it stand. This time around, the SEC did the latter.

In letters to regulators, Citigroup pointed to its post-crisis efforts at slimming down. In early 2009, Citigroup created Citi Holdings, a repository for troubled assets and lines of business the bank hoped to spin off. Since then, the bank said it has disposed of more than $500 billion of assets, leaving Citi Holdings with just 6 percent of the company’s assets.

Citigroup’s total assets peaked at $2.4 trillion in 2007, just before the financial crisis. Today, after years of steady divestitures, the bank holds $1.7 trillion in assets, $300 billion less than in 2010. The company did not respond to requests for comment by press time.

“Our institution today is stronger, simpler and safer,” Citigroup Chief Financial Officer John Gerspach told a conference call with investors last year. “We are no longer trying to be everything to everyone,” Gerspach continued, citing a renewed focus on traditional consumer, corporate and private banking.

These efforts, the bank argued unsuccessfully to the SEC, showed a breakup study would be redundant. Referring to Naylor, Citigroup wrote the board “shares the proponent’s goal of divesting noncore assets.”

Naylor sympathized with that notion, but only to a point. “We agree on the problem. We even agree on the trajectory of the solution,” Naylor said. “Now it’s a question of dosage.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.