Beirut Trash Protests: In Lebanon, The Unemployed Find Work Selling Food, Drink To Crowds

BEIRUT-- Lebanese flags, chanting demonstrators and poster-wielding protesters surrounded Bassam Sarhal as he wove through the massive crowd at Beirut’s latest anticorruption protest. Sarhal, a slight, deeply tanned man in his fifties, dodged rowdy teenagers and ducked under flagpoles. The plastic cups of orange and lemon juice on the tray he was holding never wobbled.

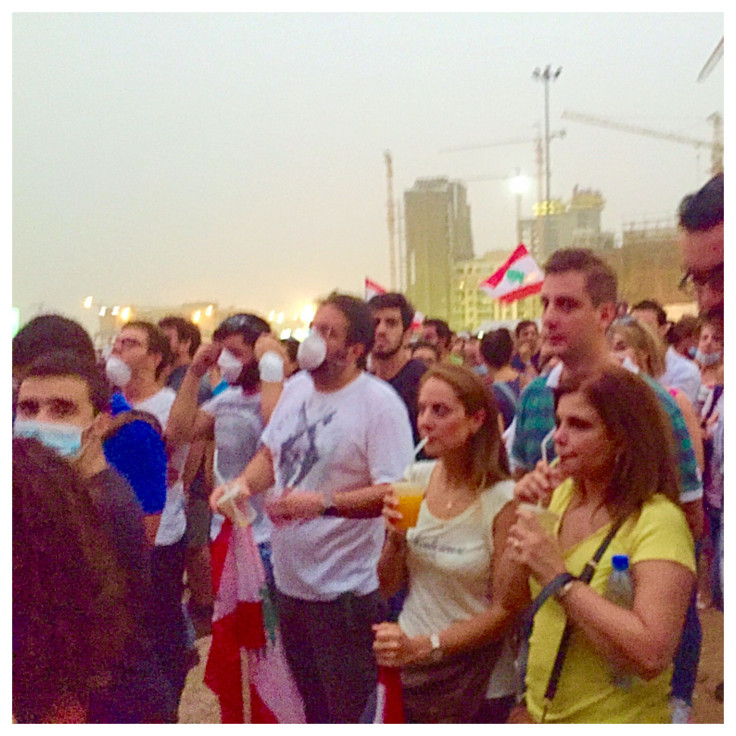

Sarhal was one of the dozens of vendors in Beirut's Martyr's Square on Wednesday who were selling snacks, sandwiches, water and cigarettes to the thousands of protestors. Large crowds of thirsty, hungry and hot people present a much-needed opportunity to make some money. Though the vendors aren't part of Lebanon's growing movement against government "greed," they represent Lebanon's major problems: unemployment and poverty.

The You Stink activist group organized the first protests in Beirut last month, after the capital’s biggest landfill closed when politicians could not agree on revenue allocation. Protests have been taking place almost daily in the capital, despite the exhausting heat and blinding sandstorm that hit the city this week.

For Sarhal, who has two children and a nephew to support, the You Stink campaign’s continued rallies mean only one thing: more heat-stricken protesters who are customers buying his juices.

“I don’t have money,” Sarhal told International Business Times, while frantically handing out juice to thirsty protesters. (His nephew passed out straws.) “I don’t support the protest, but I come here to sell my lemon juice to put my children through school.”

Sarhal is part of the more than 50 percent of Lebanese people who are able to work but cannot find jobs. Officially, the country has a 24 percent overall unemployment rate; youth unemployment is much higher, according to a 2014 report from the International Labor Organization. At 35 percent, the rate of unemployed Lebanese citizens between the ages of 15 and 24 is more than double the global unemployment rate of 13 percent.

But even those who are nominally employed in Lebanon say their wages are not enough to live on -- and that working at protests is actually more profitable than a regular job. More than 50 percent of employed people did not have a work contract and worked irregularly or independently as of 2014, according to a report from The Civil Campaign for Electoral Reform, an advocacy organization aiming to reform Lebanon’s electoral system.

Marwan abu-Hanafi used to work in a telecommunications and engineering company but recently quit his job because he was making only $700 a month. Now he can make about $100 a day at protests and other large gatherings, selling bread and pressed-cheese sandwiches at 2,000 Lebanese pounds ($1.30) each.

“I come here just to sell sandwiches and make money,” Hanafi said.

In the last two weeks, the You Stink demonstrations have splintered into different and sometimes opposing campaigns -- each holding their own rallies. Most vendors don't discriminate among protests: They go to them all.

When asked if he supported the You Stink movement, Mahamd Majzoub, the owner of an ice cream van, scoffed and said “Sure.” Then he clarified, "I'm here just to make money.”

“I always come when there is a large gathering, always we come to every protest,” Majzoub said.

Majzoub said he did not need special permission to park his van just a few feet from the campaign’s main stage at the protest. From the side door, he sells orange slushie drinks called friscos, soft-serve ice cream -- both of which he makes at home prior to protests--and cigarettes. Revenues from a protest like the one on Wednesday can total roughly $200, $30 of which goes directly to him, he said.

“I don’t have enough money to start my own company. I only have my van,” he said.

Lebanon’s population is composed of a very small class of the very wealthy and a much larger lower class. Lack of data on the issue and a rapidly changing population make it difficult to estimate how many people live below the poverty line, but research in the 2014 book Profiles of Poverty -- the human face of poverty in Lebanon estimated that roughly 30 percent of the Lebanese population is poor. That estimate rises to 40 to 45 percent if migrants and refugees are included.

The shaky economy has been battered further in the past few years as refugees fleeing the civil war in Syria next door began to seek haven in Lebanon. There are at least 1.2 million documented Syrian refugees in Lebanon, but the actual number is estimated to be much closer to 2 million.

“The Syrian conflict has exacerbated economic, political and security challenges, harming key economic drivers such as tourism, trade and banking,” according to a report from the UNDP.

Syrian refugees are not permitted to work in Lebanon, but with families to feed and decreasing humanitarian aid, many have to find alternative ways to make an income. They often work for much lower rates than Lebanese workers.

Desperate for money, many Syrian children are also forced to work. A young Syrian boy who is clearly well below the legal working age in Lebanon hands out ice water with Majzoub at protests. Majzoub called him “an employee” but declined to say how much the boy was paid.

Ahmad, a Syrian refugee from Aleppo whose name has been changed for security reasons, also saw Beirut’s recent string of protests as an opportunity to make money for his four children. He was the father of five, but his baby daughter recently died in a hospital in Lebanon’s southern city of Saida just hours after she was born because of a lack of oxygen.

Not far from al-Hanafi’s sandwich stand, Ahmad was selling all kinds of snacks, cold water and tissues. Organized by type of snack -- chips with salty items, cookies with sweet items -- his stand also had a lamp so that protestors could see him in the dark.

Beirut’s protest vendors are often met with happy cries from protesters who are parched from singing and chanting in the dusty square. Sarhal could barely keep his juice on the tray for a minute before demonstrators began waving money at him, hoping to get his attention and some orange juice. Business at the protests was brisk and though, at $1.30 a cup, it's not much money, anything helps, al-Hanafi said.

Before running to refill his juice tray, he summed up his situation with the same phrase used by all of the country’s economic classes to express both their helplessness when it comes to the failing infrastructure and how common these issues have become: “Welcome to Lebanon!”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.