With Billions Of Dollars in Gulf Aid, Egypt's Sisi Has Easier Job Fixing Economy

As Abdel Fattah el-Sisi gets ready to become Egypt’s next president, his first challenge will be to fix the Arab world’s most populous nation's economy. He will need to address rampant unemployment, a growing deficit, and the problem of energy subsidies -- which make life affordable for Egyptians, but cost the government money it doesn’t have.

Sisi is also faced with a crippling budget deficit, which the government’s own forecast says will run in the coming fiscal year to almost 14 percent of gross domestic product. But, analysts say, the newly elected president does not have the urgency to move quickly on reform programs to cut runaway public spending -- because he is receiving billions of dollars in aid from Gulf states.

During the presidency of Muslim Brotherhood-backed Mohammed Morsi, Qatar announced that it would invest $18 billion in Egypt over five years. Other Gulf nations followed, pledging billions to help stabilize cash-strapped Egypt. Despite Morsi’s ouster in a coup last year, the investments remain intact, and Sisi has said he plans to use part of the money for large infrastructure projects, particularly in the south.

Those might help relieve unemployment, which officially stood at 13.4 percent in the first quarter of 2014. Experts say development projects will also create new opportunities for investment, creating confidence in the economy.

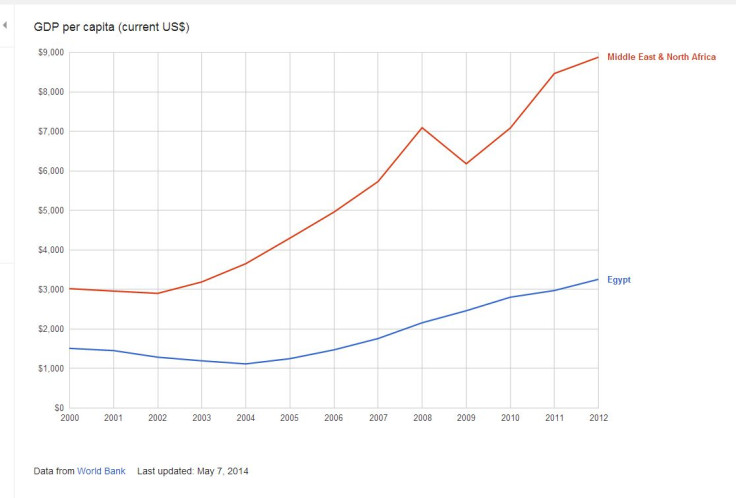

Since the beginning of the revolution in 2011, the Egyptian currency plummeted, inflation increased, and the budget deficit grew. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), annual growth dropped to 1.8 percent in 2011 from 5.1 percent in 2010. The pace of growth is picking up, but Egypt remains a nation of 80 million with a GDP per capita just above $3,200, growing at a far slower pace than its Mideast peers.

“Sisi sort of implied in the first two years that will be his focus on getting things back to normal,” Paul Salem, vice president for policy and research at the Middle East Institute in Washington, said. “He will start first with major development projects to inject money into the economy.”

An even bigger concern than unemployment is the fiscal burden of energy subsidies, which have increased the government deficit significantly over the past several years. Egypt is the largest oil producer in Africa that is not a member of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), and the second-largest natural gas producer on the continent, and it subsidizes fuel heavily -- a popular measure, which has put the country in billions of dollars of debt.

The Egyptian government pays foreign companies market prices for oil, and then sells the refined fuel to local consumers for a discounted price. Now it owes those companies about $6 billion.

Yet that’s an issue that Sisi will not begin tackling in the short term. “Sisi has said he will move slowly on reducing subsidies because he knows that will be painful for the people,” Salem said.

With so much money flowing in from the Gulf, Sisi can focus his attention on other areas of the economy because he now has “money to cover the deficit,” he said. But eventually, he will need to tackle the problem.

According to Fitch Ratings, without “significant fiscal reform” Egyptian government debt will remain at 90 percent of GDP, well above Egypt’s rating peers. The agency took Egypt’s long-term foreign currency rating off negative outlook for the first time since January 2011, citing tentative improvements in political and economic stability.

One way the government has tried to mitigate the impact of fuel subsidies has been by handing out smart cards designed to monitor fuel consumption at the pump, which will help direct subsidies to those who need them most. Angus Blair of the Signet Institute, a think tank for analysis of the Middle East and North Africa, said the smart cards will also help prevent fuel from being sold illegally on the black market.

The decision to begin using smart cards to distribute gasoline and diesel was a step toward meeting IMF terms for a loan. The organization is requiring that Egypt reduce its deficit before it hands over a $4.8 billion loan.

Even with the Gulf money and possibly the IMF loan giving him some breathing room, Sisi needs to worry right now about how to keep the lights, and for those who can afford it, air conditioning on when the hot Egyptian summer arrives, with its heightened energy demand.

Beyond the summer, Sisi will have to address larger economic issues like how to create jobs sustainably, and will need to start thinking about long-term prosperity. But he has no experience in business and comes from a pure military background.

“If we look further down the road to look at what it would take to start generating jobs, this is there is a big question mark regarding Sisi and where he is going to go,” Michelle Dunne, a senior associate at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, said, adding that Sisi could come into office with a “statist perspective” regarding the economy.

The World Bank predicts that the Egyptian economy will grow about 2.3 percent in 2014, up from 1.8 percent in 2013. But according to Dunne, Egyptians realistically may not see improvements in their day-to-day lives right away.

“Sisi needs to make Egyptians feel that things are turning around,” she said. “His support will drop if there isn’t some tangible improvement within one year.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.