Body Size Of Vertebrate Species Linked To Extinction Risk, Study Finds

Even as scientists have warned that a sixth mass extinction may be coming — with over 30 percent of all vertebrate species declining in numbers over the past 25 years — researchers who carried out a global analysis of thousands of species have found that body size of vertebrate species is an important factor in determining how much risk they face in terms of going extinct. The other important factors, according to the study, was the size of the habitat for the species — especially the smaller ones — and human activity.

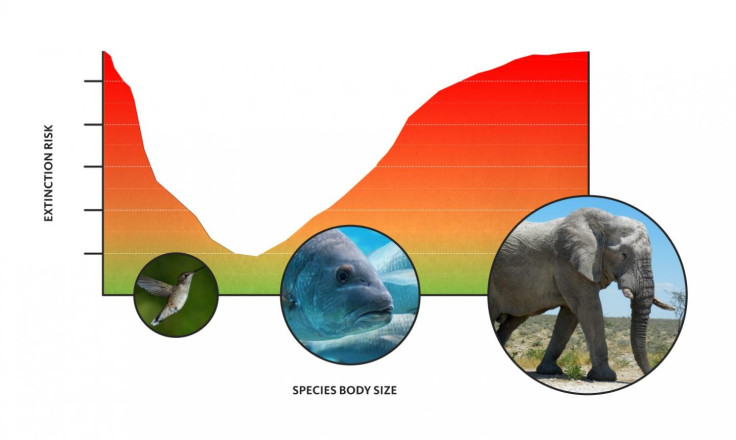

In a paper titled “Extinction risk is most acute for the world’s largest and smallest vertebrates” that appeared online Monday in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the researchers first put together a database of body masses of 27,647 vertebrate species, and the analysis of their extinction threat levels found the smallest and largest vertebrates at the highest risk. These included land animals, reptiles, amphibians, birds and marine creatures as well.

“Knowing how animal body size correlates with the likelihood of a species being threatened provides us with a tool to assess extinction risk for the many species we know very little about,” William Ripple, a professor of ecology at Oregon State University and lead author of the study, said in a statement Monday.

Ripple and his colleagues — from Australia, Switzerland and the United States — considered species assessed by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature in its Red List of Threatened Species, of which some 4,400 face the risk of extinction.

They found that while mid-sized animals have a relatively low extinction threat, the problems faced by large and small species are different.

“Many of the larger species are being killed and consumed by humans, and about 90 percent of all threatened species larger than 2.2 pounds (1 kilogram) in size are being threatened by harvesting. Harvesting of these larger animals takes a variety of forms including regulated and unregulated fishing, hunting and trapping for meat consumption, the use of body parts as medicine and killing due to unintentional bycatch,” Ripple said.

At the other end of the scale, the smallest threatened species usually weigh less than 3 ounces (77 grams) in body weight, and suffer most due to loss or degradation of habitat, which is usually a result of human activities like pollution, logging and agriculture. The worst affected are the small species that live in freshwater habitats.

Some specific examples of large species that need to be focus of conservation activities, as listed by the authors, include the whale shark, Atlantic sturgeon, Somali ostrich, Chinese giant salamander and the Komodo dragon. Similarly, examples of small vertebrates that are especially imperiled included the Clarke's banana frog, sapphire-bellied hummingbird, gray gecko, hog-nosed bat and the waterfall climbing cave fish. A range of different conservation strategies will be needed to save these varied species from disappearing forever, the researchers said.

“Our results offer insight into halting the ongoing wave of vertebrate extinctions by revealing the vulnerability of large and small taxa, and identifying size-specific threats. Moreover, they indicate that, without intervention, anthropogenic activities will soon precipitate a double truncation of the size distribution of the world’s vertebrates, fundamentally reordering the structure of life on our planet,” the paper said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.