BP Oil Dispersant May Facilitate Skin Absorption Of Crude Oil

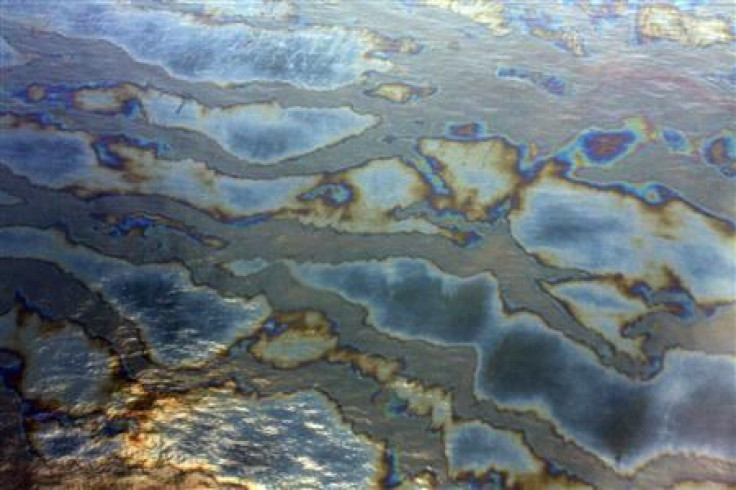

A study conducted along the Florida coast suggests the Gulf of Mexico is far from decontaminated two years after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, and that a dispersant used in the aftermath of the spill may be partly to blame.

According to a study by James Kirby, a graduate student at the University of South Florida's Department of Geology, the Gulf Coast from Mississippi to Florida remains littered with tar balls and other tar products formed after BP's use of oil dispersants.

What his study suggests is the use of Corexit, a toxic oil dispersant banned in the United Kingdom but approved for use in the U.S. by the Environmental Protection Agency, delayed the rate at which oil naturally decomposes.

Corexit in lab tests, Kirby said, actually prevents the natural degradation and elimination of crude oil, by killing off the the bacteria that would consume it. The use of the chemical actually slowed the rate at which oil naturally weathers, thus increasing the likelihood that bathers and people along Gulf beaches come in contact with oil, tar and dispersed residue trapped in sand or in the water.

By design, oil dispersants are supposed to help oil clump together and sink to the bottom of the ocean where, over time, they will dissolve and decompose.

Following the April 20, 2010 fire that sank the Deepwater Horizon and caused the worst environmental disaster in U.S. history, BP sprayed oil sheens in the Gulf with at least 1.8 million gallons of Corexit, reported The Christian Science Monitor.

But Corexit did not fully do what it was intended to.

Kirby's team noticed on the Gulf beaches oil residue and tar products -- that could not be specifically linked to the 2010 oil spill -- that were coated in BP's Corexit.

What is more alarming is an accidental finding that suggests the residual oil found on the beaches was quickly, and inexplicably, absorbed into the legs of one of his researchers. The findings were released this month and published by the Surfrider Foundation.

Oil, when under ultra-violet light, has a distinctive appearance. That distinctive hue, Kirby said, was suddenly visible on the skin of one of his researchers after he waded and knelt in shallow water off the Florida coast. No matter how many times he washed himself, the oil would remain, Kirby said, suggesting that it had been absorbed by human skin, in a relatively short time frame.

I don't know what was absorbed through the dermal boundary, Kirby said.

Wet skin is naturally more porous than dry, but crude oil by itself is not quickly absorbed into human skin, Kirby said, who added that he's not sure if Corexit facilitated the absorption.

An earlier form of the dispersant used in the response to the Exxon Valdez spill of 1989 in Alaska, has been linked to health problems including respiratory, liver, lung and nervous system disorders in humans, Propublica reported.

Toxicology studies to determine effects of Corexit dispersant on dermal absorption rates of carcinogenic [Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons] through wet skin are needed to assess risk to human health and safety, read the report.

And while such a test is not being conducted, Kirby still thinks companies should use a different type of dispersant if they want to dissipate and help remove oil from the Gulf of Mexico or any future oil spill.

Corexit should be banned from use in the U.S. and the rest of the world, Kirby said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.