California Drought: Strongest El Niño In Years Still Won't End The Crisis

California’s brutal drought will press on into 2016, despite signs that a powerful El Niño this winter will bring higher-than-normal rainfall to parts of the state. The Central Valley and other major food-growing regions aren’t expected to bounce back soon from an enduring water deficit that has so far cost the state’s agricultural sector billions of dollars and thousands of jobs.

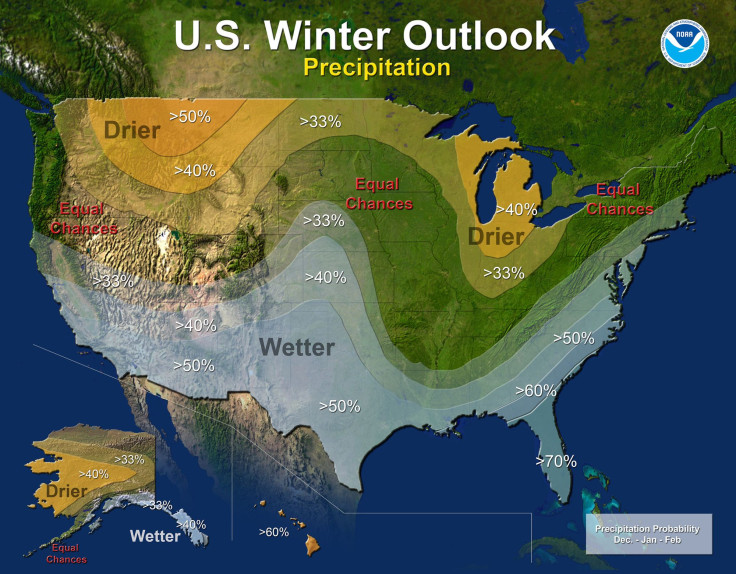

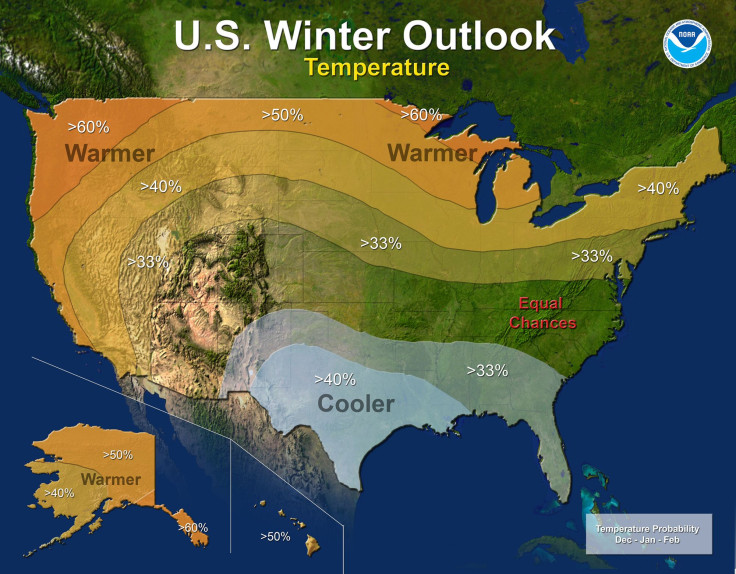

The warm El Niño phenomenon forming in the Pacific Ocean could be among the top three strongest events since 1950, Mike Halpert, deputy director of NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center, told reporters Thursday. The pattern could lead to wetter-than-average conditions across the southern half of the lower 48 states, from Southern California through Texas, Florida and up into the Northeast. Much of the West and northern half of the U.S. could see above-average temperatures, while southern Plains states and the Southeast could see a cooler-than-normal winter.

El Niño conditions could provide some relief in central and Southern California by the end of January, but rains won't be enough to propel it out of drought. Almost half the Golden State is experiencing exceptional drought levels -- the worst of five drought classifications -- while the other half is seeing at least some degree of drought. Farmers are watching their crops shrivel and livestock suffer as water costs soar and supplies disappear. California’s economy is expected to lose a combined $4.9 billion in output and economic activity in 2014 and 2015, of which $3.34 billion, or nearly 70 percent, comes from the agricultural sector, according to researchers at the University of California, Davis.

In the Central Valley region, the cumulative precipitation deficit from years of drought is equal to nearly three times the average annual precipitation, Alan Haynes, a hydrologist with NOAA’s California Nevada River Forecast Center, said on the Thursday call. He noted that California’s key reservoirs are well below half their normal average capacity for this time of year, while groundwater supplies are significantly stressed.

“Even if the wettest year on record were to occur, it still wouldn’t erase the deficit that’s occurred over the last four years,” he said.

Above-average rains brought by El Niño might not all come as a relief: Flash floods and landslides are all common during El Niño years. Still, the extra rain might help stave off another natural threat, wildfires. California has seen a series of destructive blazes this summer as drought and climate change turn the state into a hot, dry tinder box.

During an El Niño, warm equatorial waters that pool near Asia and Australia are propelled toward the Americas by shifting winds and currents. The west-to-east commotion has the effect of raising the ocean’s overall surface temperature, which in turn can elevate air temperatures and alter precipitation patterns. Often in an El Niño, the water ocean water flings more moisture into the air, increasing the potential of heavy or replenishing rains. (La Niña is the opposite phenomenon, characterized by unusually cold Pacific temperatures and dry conditions on the West Coast.)

Other factors, including the Arctic Oscillation and the Madden-Julian Oscillation, can influence temperatures and precipitation levels during winter months.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.