El Niño Explained: What Is This Weather Phenomenon And What's On Tap For 2014?

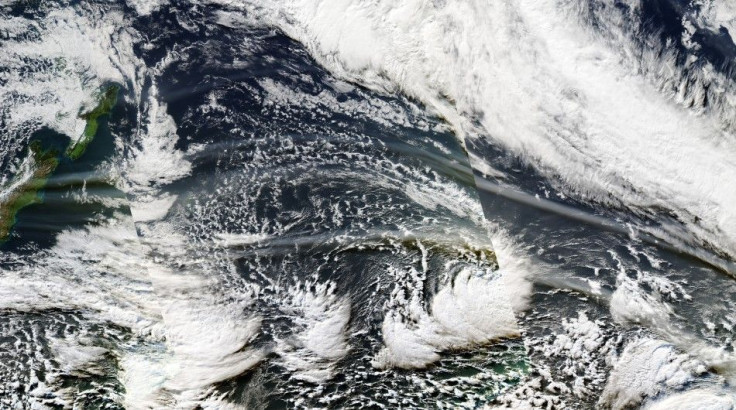

An El Niño weather system is forming over the Pacific Ocean this summer, and scientists are watching closely to see how strong the event might be.

The answer could help determine how high global temperatures will rise this year, how severe a drought could afflict Australia and Asia, and whether or not rain-starved California will get the precipitation it desperately needs. All of this depends on how the waves in the Pacific respond to the winds overhead, and vice versa.

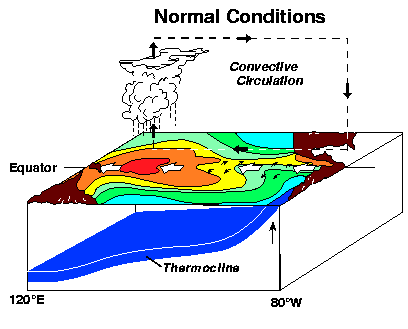

To understand how an El Niño works, it helps to know what happens during “normal” conditions.

In the Pacific Ocean, the water closest to the equator is warmed by the sun. That warm surface water helps to create more clouds, which in turn dump rain over wherever they happen to be.

Most of the time, the wind over the ocean blows from east to west due to the spinning of the Earth. Those gusts—called prevailing winds—continuously skim off the warm water like cream and push it toward Asia and Australia. The water near the Americas, as a result, is usually cooler by comparison.

The warm water builds and builds in the east, “until at some point, the system says, ‘Whoa, too much! I’m going to get rid of it!’” Kevin Trenberth, a climate scientist at the U.S. National Center for Atmospheric Research in Colorado, explained.

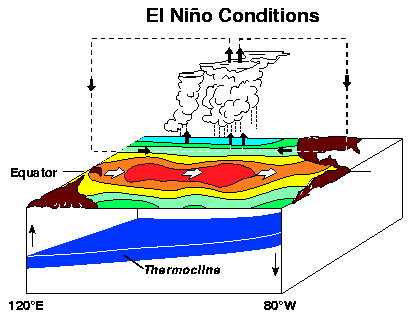

This is when an El Niño event has the potential to kick in.

It usually happens every three to seven years, starting slowly in the summer, peaking in the winter and dying off quickly in the New Year. Peruvian fishermen are credited with naming the event after they noticed that every few years around Christmas, virtually no fish could be found in the unusually warm waters. (“El Niño” is Spanish for “The Christ Child”).

El Niño events are aided by oceanic Kelvin waves. These undulations only travel west to east, so they effectively shed the warm layers in the Asia-Australia region like a dog would its winter fur coat and send the warmth east. Strong westerly bursts can propel the warm water even farther, pushing greater amounts closer to the Americas and leaving cooler waters behind in the western Pacific.

This shift in warmth — and thus change in clouds — increases the potential of heavy rains, flooding and disrupted fish habitats near the Americas and creates drought conditions in the western Pacific. It also boosts the number of tropical storms and hurricanes in the eastern Pacific while decreasing activity in the Atlantic Ocean, Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea.

As the warm water moves west to east, the winds slosh it all around in the ocean. This increases the overall sea surface temperature, and that in turn heats up the atmosphere. Trenberth called this phenomenon a “mini” global warming event. It’s largely why 2010, the year of the most recent El Niño event, was also the hottest year on record, according to U.S. scientists.

This feedback between the waves and winds is ultimately what decides whether an El Niño event will form—and if it will be weak, moderate or strong, Tim Stockdale, a principal scientist at the European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts near London, said.

“Things in the ocean move pretty slowly and they’ve got a lot more inertia, whereas the atmosphere flips around at random,” he said. “The eventual outcome [of El Niño] will depend on the signal in the ocean, but also on the random element of what the atmosphere might do.”

Officially, an event is deemed a weak El Niño event if the sea surface temperatures increases by more than 0.5 degrees Celsius (0.9 degrees Fahrenheit) above normal. At 1.0 degree Celsius above normal, an event is moderate, while anything above 1.0 degrees is considered strong.

(A La Niña event is essentially the opposite, characterized by unusually cold ocean temperatures near the equator in the Pacific).

Earlier this year, scientists thought that the strong wave activity they observed in the Pacific might set off an especially strong El Niño event. In February, an oceanic Kelvin wave achieved the same strength as the one that preceded the 1997-98 “super” El Niño, which caused $33 billion in damages and was blamed for about 23,000 deaths worldwide. Observers worry that the Earth might be gearing up for something equally as destructive in 2014.

Since February, however, eastbound prevailing winds have picked up, diminishing the risk of a super El Niño. “We didn’t see that real force we needed to see in the early part of the spring” to create such an event, Michael Ventrice, an operations scientist at Weather Services International in Boston, explained.

El Niño watchers shouldn’t have to wait too much longer to see how this year’s El Niño will shape up.

The World Meteorological Organization, the U.N.’s weather agency, put the odds of El Nino at 60 percent between June and August, climbing to 75-80 percent between October and December, according to a June 26 update.

The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) made a similar prediction on June 5. It gave El Niño a 70 percent chance of occurring this summer and an 80 percent chance of appearing during the fall and winter.

Some climate scientists argue that the phenomenon has already started, albeit in a weak stage, even if government-run agencies haven’t officially declared it yet. “What is happening now is so different than anything we’ve seen in the last three years that weather patterns are being greatly affected—regardless of whether it’s [officially] an El Niño or not,” Trenberth, the U.S. scientist, said on June 23.

“The real question is, does it stay at that level and maybe even die off, or does it amplify and get bigger?” Stockdale added.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.