As Canada's Liberal Party Takes Office, US Military Deserters Get New Hope With Trudeau Administration

For U.S. Marine Dean Walcott, his progression from hesitant soldier to being officially AWOL began in late 2004. During his two-month deployment to Landstuhl Regional Medical Center in southwest Germany, Iraqi civilians, burned in a mortar attack in Mosul, began steadily arriving by plane for emergency treatment. The sight of children and babies dying while in extreme pain triggered Walcott's loss of belief in the war in Iraq and became the start of a struggle to find meaning in his own life. It was at that point, in his fourth year of service, that he considered Canada as a realistic place of refuge.

“On some level if it was soldiers, airmen or Marines, I could have maybe reconciled my feelings a little bit better since we were a military force in that country,” said Walcott, who entered Canada after jumping on a Greyhound bus in North Carolina in December 2006 and is currently being sought by the U.S. authorities. “But when the toddlers and babies started coming in burnt and bloody I really began to feel that I couldn’t carry on and I began looking for a way out.”

The topic of U.S. military personnel avoiding war by fleeing to Canada and the murky moral and legal landscape in which they exist is one that gained attention during the Vietnam War era, when Ottawa offered asylum to thousands of Americans trying to elude the military draft. Now, 40 years after the end of that conflict, a small group of U.S. military deserters who escaped while serving in the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts by fleeing to Canada over the last decade have been given fresh hope: Rulings by Canada's previous Conservative government, which sought to send U.S. servicemen home to face severe military punishment, could be overturned by newly sworn-in Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and the Liberal Party that took power Wednesday.

A Conservative Government

When the first U.S. war deserters began turning up in Canada in 2003, they were met with very little resistance from the then-Liberal government. However, in 2006, the Stephen Harper-led Conservative Party came to power and immediately set about trying to remove the 200 or so deserters who had crossed the border in the intervening three years. While Harper’s government managed to send many of them back to the U.S. where they faced court-martial, dishonorable discharge and time in jail, those who managed to remain in Canada faced new and far stricter immigration rules. Ass of 2010, all the deserters attempting to gain lawful immigration status in the country were no longer eligible for asylum.

The U.S. deserters were seemingly fighting a hopeless battle, recalls Michelle Robidoux, a spokeswoman, for the War Resisters Support Campaign in Canada. “The Conservatives were quite vindictive against the war resisters,” said Robidoux, whose organization is gearing up to lobby the new Liberal government. “They had a vendetta and began rejecting many of them just because of their status rather than on a case-by-case basis as immigration officials are supposed to do.”

While Walcott and others appealed the new immigration legislation in 2011 and won, Harper’s government counter-appealed, which kicked off a five-year legal battle between the Canadian government and the federal courts -- a battle that continues today.

“The court cases have made things really complicated to be here and have a family,” said Walcott, who is now married and has three Canadian children in Peterborough, Ontario, east of Toronto. “For the longest time while I was up here, I didn’t bother trying to find someone to be with because I always thought, 'Who the hell wants to be with someone who might not be here in a week?' But now I have four people that I love and I’m scared that I could lose that.”

A Liberal Hope

However, Wednesday, when the Liberal Party took power in Ottawa, Walcott and the remaining group of 20 deserters have fresh hope that the court actions against them will cease and they will be given the right to remain in the country.

And they have good reason to believe that the Liberal Party will help their cause.

During two votes, in 2008 and 2009, the Liberal Party voted overwhelmingly to allow the deserters to stay. But when a bill was finally introduced in 2010, it was defeated by only seven votes. Future Prime Minister Justin Trudeau was present that day and voted to allow them to stay.

While the plight of the deserters didn’t form a part of Trudeau’s election manifesto, in July this year he gave a fresh indication that he could be willing to allow the remaining deserters to stay in the country if he won the election. Trudeau, during a political rally in a small Manitoba town, was cornered by the wife of U.S. Army deserter Joshua Key, who demanded a review of all the deserters' cases. The now-prime minister said he would look at all the deserter cases with “openness and compassion.”

The Past

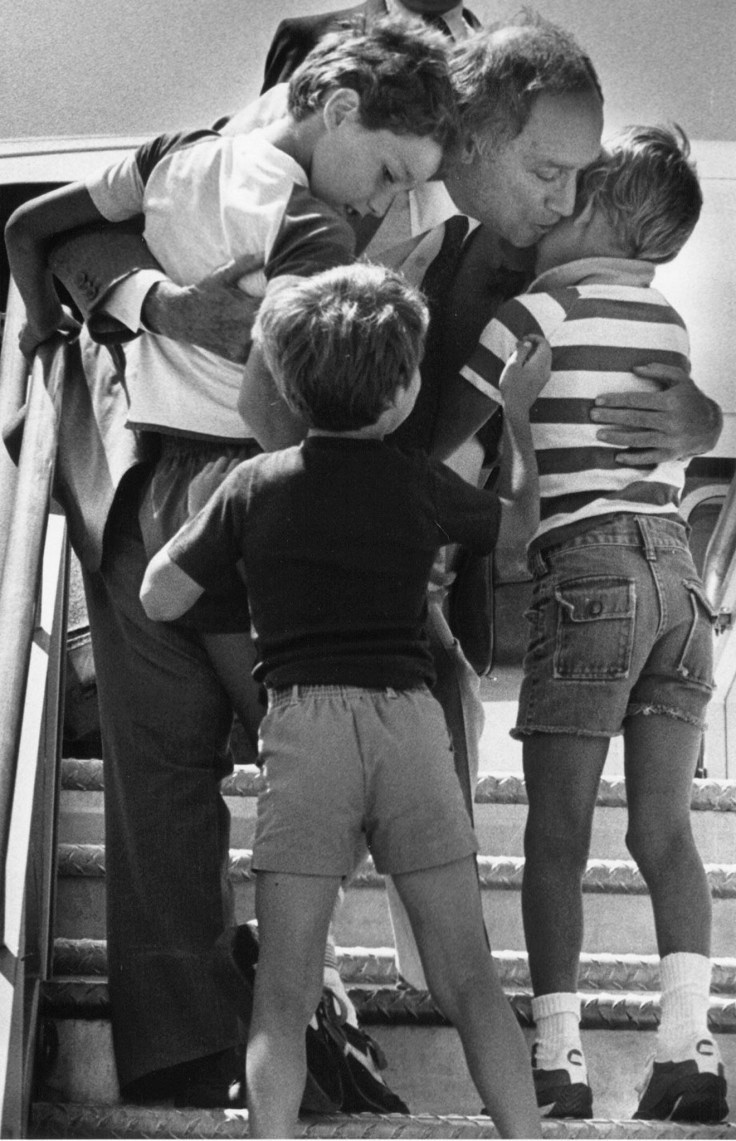

If he does, Trudeau will be following in the footsteps of his father Pierre, the prime minister of Canada from 1968 to 1979, and again from 1980 to 1984. Pierre Trudeau allowed more than 50,000 draft dodgers to use Canada as a place of refuge. Despite being given a pardon from President Jimmy Carter’s White House in 1977, many of them stayed in Canada permanently and ended up helping the newest generation of war resisters settle in their new country.

Charlie Diamond, who arrived in Canada on Oct. 23, 1968, as a draft dodger and currently lives in Toronto, began contributing financially to the War Resisters Support Campaign in Canada and lobbied members of the Canadian parliament to pass laws that would enable deserters to stay legally. He said via an email that Trudeau should start his term by making "a public statement saying that U.S. war resisters known currently and since 2004 will be able to remain in Canada as landed immigrants.” Landed status is the equivalent of the U.S. green card.

While it was not immediately clear how the U.S. government will respond to any decision by the new Liberal Party to allow deserters to stay, it’s unlikely those who walked away from military service will ever be able to enter the U.S. again without facing severe punishment, according to a U.S. Army spokesman, who said a warrant for arrest for desertion is never withdrawn.

For deserters such as Key, who came to Canada in March 2005, the difficult decision to run away from the Army while serving in combat more than a decade ago has left his four children to grow up without a father. After being unable to support the family he took with him to Canada, his wife eventually left with the kids and returned to the U.S. Key can't return without facing up to 20 years in jail, he said. The longest sentence handed down by a court-martial for desertion has been 24 months.

“I haven’t gotten to see them since they went back six years ago and I haven’t had much contact with them since then,” said Key who is currently unable to work and does not receive medication for his post-traumatic stress disorder. ”I’ve fallen off the map right now, but I’ll find them one day.”

For Walcott, who became friends with Key after they discovered each other through the War Resisters Support Campaign, having the Liberal Party help him stay in the country lawfully would mean he could unshackle himself from more than a decade of doubt and uncertainty that has plagued him since he began to question the war in Iraq back in 2004.

“For the last 12 years I’ve had to live with this notion that I’m damned as part of the Marine Corps and then in limbo up here in Canada, but now I’m seriously hopeful for the first time in years. It’s breathtaking in a way,” he said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.