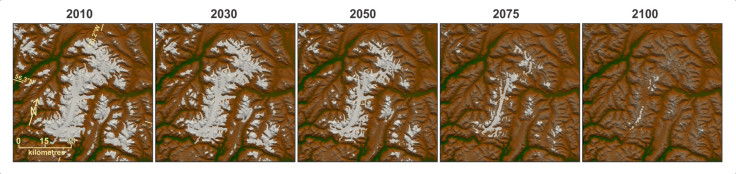

Canada's Rocky Mountains Could Lose 90% Of Its Glaciers By 2100

By 2100, inland glaciers in Canada’s Rocky Mountains could lose up to 90 percent of their ice if current trends of greenhouse gas emissions continue unabated, according to a new study published Monday in the journal Nature Geoscience. Moreover, according to the study, carried out by a team of scientists from the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, the overall loss of ice in glaciers of Western Canada by the end of the twenty-first century could be as high as 70 percent.

“Soon our mountains could look like those in Colorado or California and you don’t see much ice in those landscapes,” Garry Clarke, a professor at the University of British Columbia and the lead author of the study, said in a statement. And, given that a substantial chunk of the region’s population depends on these glaciers for water supply and hydropower, their loss would directly impact millions of people.

However, Clarke added, a more direct impact would be visible on the freshwater ecosystems in British Columbia and Alberta. “These glaciers act as a thermostat for freshwater ecosystems … once the glaciers are gone, the streams will be a lot warmer and this will hugely change fresh water habitat,” he said in the statement.

While previous climate models have described the melting of glaciers in broad terms, the latest study assesses the impact of anthropogenic climate change on individual glaciers. As a result, a drastic difference in the projected extent of deglaciation becomes visible. For instance, the study predicts that glaciers in the drier regions of the Rocky Mountains would be the worst affected -- shrinking to less than 10 percent of their current area. In the same time period, glaciers in the wetter coastal mountains in northwestern British Columbia are only expected to lose about half of their volume.

“The glaciers don’t respond to weather; they respond to climate,” Clarke told the New York Times. “Last year’s bad winter is not going to save the glaciers. On average, climate is changing, and it’s not changing in ways that are good for glacier survival.”

The projections are based on the greenhouse gas emission scenarios used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in their most recent report. According to the study, there is a possibility -- however unlikely -- that if emissions peak in 2020 and then decline, several inland glaciers could be saved.

“In that case, many inland glaciers would shrink, but they wouldn’t disappear. That’s the good news side of the equation,” Clarke told Climate Central.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.